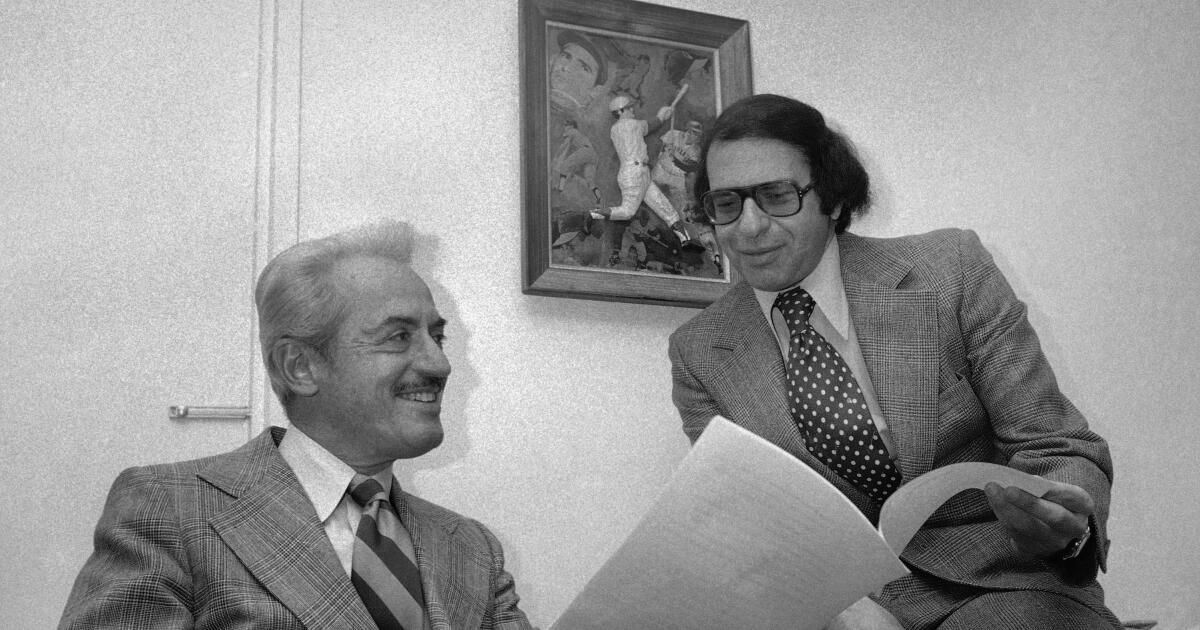

Dick Moss, who earned the trust of powerful union leader Marvin Miller while representing the United Steelworkers of America and then proved that trust was well-placed by winning the arbitration case that created free agency for Major League Baseball players nearly 50 years ago, has died. He was 93.

The 1975 case involved Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith and led to arbitrator Peter Seitz striking down the reserve clause, the restrictive contract language that had kept players under perpetual team control for nearly 100 years. Seitz was swayed by Moss’s arguments and narrowed the clause’s definition, ruling that it meant only a one-year renewal, a decision that led to collectively bargained free agency.

Baseball appealed the ruling, but it was upheld in federal court in 1976, with Moss defending the players. Later that year, the free agency rules became the basis for a collective bargaining agreement between MLB and the players' union.

“The difference between winning and losing can be expressed in billions of dollars,” Moss said at a party at his Pacific Palisades home to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the ruling. “I don’t think you can find another employment arbitration case that can say that.”

Moss died Saturday at an assisted living facility in Santa Monica, according to his niece, Nina Wiener. Although he was born and raised near Pittsburgh, he spent much of his adult life in the Los Angeles area.

Richard Myron Moss was born on July 30, 1931, to Nathan and Celia (Rosenblatt) Moss. He earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1952 and a law degree from Harvard in 1955 before serving in the Army for two years.

He worked for the Pennsylvania state government before joining the steelworkers union in 1960, where he met Miller, who would become his mentor. Six years later, Miller became the first executive director of the MLB Players Association, bringing Moss with him.

The two lawyers soon began educating players about union strategies. In 1968, they drafted baseball's first collective bargaining agreement, and by 1970 they had negotiated an arbitration system.

“Working as a team was exactly what built the solid foundation,” former pitcher Steve Rogers, a Moss client and longtime union official, told the Associated Press. “Nothing that is happening today exists without a solid foundation.”

Moss met outfielder Curt Flood, who challenged the reserve clause in federal court after refusing to report to the Philadelphia Phillies when he was traded by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1969. Although Flood lost his case in the U.S. Supreme Court, the inherent injustice of players being prevented from signing with the highest bidder became apparent.

The New York Yankees emerged as the franchise most willing to pay players salaries never before seen, inadvertently aiding the efforts of Miller and Moss.

First came the case of pitcher Catfish Hunter, whom the Yankees signed to a five-year, $3.25 million contract in 1974 after Moss claimed that Hunter's one-year, $100,000 contract with the Oakland Athletics was invalid because of a dispute over a deferred insurance annuity. Moss pointed to Hunter's contract with the Yankees as proof that in an open market players would make far more than they did with the reserve clause in place.

Then came the cases of pitchers Messersmith and Dave McNally, who refused to sign what they considered substandard contracts for the 1975 season.

Their teams responded by renewing their contracts on the 1974 terms, which in Messersmith's case were $90,000 and grossly unfair. The right-hander had led the Dodgers to the 1974 World Series and finished second in the NL Cy Young Award voting after leading the league with 20 wins while posting a 2.59 earned run average in 292 innings.

Playing without a signed contract in 1975, Messersmith had another standout season, leading the National League with 19 complete games, seven shutouts and 321 innings while posting a 19–14 record and a 2.29 ERA.

Moss represented Messersmith and McNally — who had also pitched without a contract in 1975 — in arguing that a player should become a free agent one year after his contract expired. After this so-called “option year,” Moss argued, a player should be allowed to offer his services to the highest bidder.

Moss took the case to Seitz, who ruled that the teams had “no right or power” to retain the services of Messersmith and McNally beyond the one-year renewal that had already expired. The ruling was upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals, and free agency rules were written into a collective bargaining agreement in 1976.

A year later, Moss left the union to become an agent and eventually represented Dodgers pitching phenom Fernando Valenzuela as well as future Hall of Famers Nolan Ryan, Gary Carter and Jack Morris.

After Ryan's three-year, $600,000 contract with the Angels expired following the 1979 season, Moss negotiated a four-year, $4.5 million contract with the Houston Astros, making Ryan the first MLB player to be paid $1 million a year. Moss also argued the cases with the Dodgers that earned Valenzuela his first million-dollar salary through arbitration in 1983 and made him the highest-paid pitcher in baseball with a three-year, $5.5 million contract by avoiding arbitration in 1986.

Moss is survived by his third wife, Carol Freis, whom he married in 1980, and a daughter from his second marriage, Nancy Moss Ephron. Another daughter from his second marriage, Betsy, predeceased him.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.