Former President Trump has not yet officially won the Republican presidential nomination. But he is already exerting his influence on foreign policy, and Republicans in Congress are falling in line.

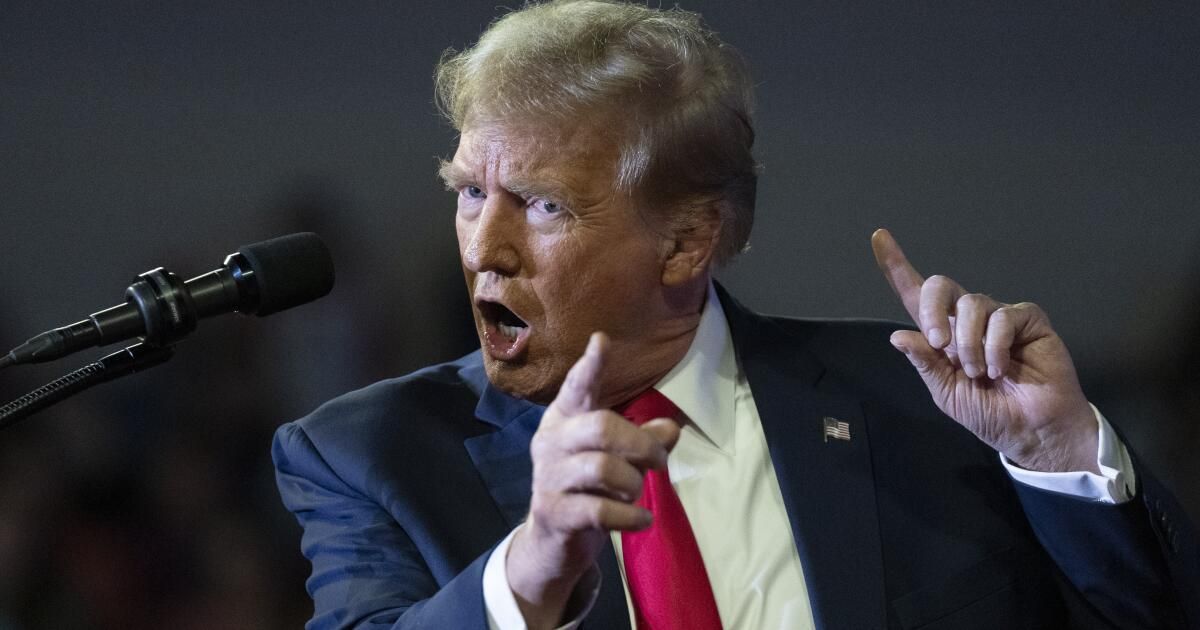

At a campaign rally this month in South Carolina, Trump said he would encourage Russia to attack U.S. allies that don't spend enough on defense.

“No, I would not protect them,” the former president told European leaders. “In fact, I would encourage [Russia] do whatever they want.”

It was an extraordinary statement for a presidential candidate, and it drew rebukes from President Biden, who called it “shameful” and “un-American,” and from European leaders. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said any suggestion that the United States would not defend its allies was “dangerous” and “only in the interests of Russia.”

But most Republicans in Congress excused it as yet another example of Trump being Trump.

“I don't have any concerns,” said Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida. “He does not speak like a traditional politician and we have already been through this. “You would think people would have noticed by now.”

That wasn't Trump's only foreign policy intervention this month. He also pressured Republican senators to block a bill containing $60 billion in aid to Ukraine and said any future aid should be limited to loans rather than grants.

Most Republicans also gave up. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, once a fierce supporter of Ukraine, said Trump's opposition persuaded him to switch sides.

Trump's positions were not entirely new, except for the innovation of encouraging Russia to attack US allies. During his four years as president, he frequently accused Germany and other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization of owing the United States billions of dollars for supporting their defense, as if they owed nonexistent “unpaid dues” or as if the alliance was a protection fraud. He ultimately focused on the more reasonable complaint that some NATO members were not meeting the alliance's defense spending targets, but he still told his aides that he wanted to pull the United States out of NATO. completely.

He repeatedly praised Vladimir Putin (and still does); Earlier this month, she praised the Russian president as “very smart, very smart.” Until Sunday, Trump remained silent about the death in an Arctic prison colony of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, except for a cryptic social media post suggesting Biden has persecuted him in the same way Navalny was persecuted by Putin. . And he has frequently expressed hostility toward Ukraine.

Here's what's different this time: In Trump's first term, Republicans in Congress and his own foreign policy advisers convinced him not to act on most of those impulses. If he wins a second term, those restrictive forces will mostly disappear.

The former president has said he intends to fill a second Trump administration with MAGA loyalists rather than establishment figures like Defense Secretary James N. Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson who populated his first term.

“When I went there [to the White House], I didn't know many people; In some cases I had to rely on the RINOs,” Trump said last year, referring to “Republicans in name only.” “But now I know them all. I know the good ones. I know the bad ones.”

Congress will also be different. Since Trump was elected in 2016, dozens of establishment Republicans in the House and Senate have dropped out or lost their seats to pro-Trump candidates. Others will leave at the end of their current terms.

Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, a frequent Trump critic, will give up his seat at the end of the year. Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, whom Trump has ridiculed, says he plans to remain in the Senate but will likely face a challenge for his leadership position.

Others, like Graham and Rubio, who once criticized Trump, have trimmed their sails to avoid clashing with him. Last year, Rubio co-authored a law that prohibits a president from withdrawing the United States from NATO without congressional approval, but that won't stop Trump from undermining the alliance by saying he won't defend its members.

The cumulative result has been the unleashing of Trump and a sea change in Republican foreign policy. For 60 years, from 1952 to 2012, the Republican Party was led by largely hardline internationalists, from Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan and Romney.

Trump's foreign policy instincts represent a different strain — xenophobic, distrustful of alliances, unilateralist on some issues and isolationist on others — that has taken root among Republican voters.

Last year, a poll sponsored by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs reported that a majority of Republicans want the United States to “stay out of world affairs” rather than actively participate. This was a striking change from previous decades. As recently as 2017, the first year of Trump's presidency, 70% of Republicans said they favored an assertive American foreign policy. Last year, that figure had fallen to 47%.

In the same poll, only 40% of Republicans favored military aid to Ukraine, compared to 76% of Democrats. As expected, opposition was strongest among voters most attached to Trump.

Old-school internationalists in both parties warn that the consequences of a second, less restrained Trump term would be dire.

“If Trump is re-elected, adversaries will be emboldened and allies will be frightened,” said Kori Schake of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, who worked in the George W. Bush administration. “Allies are likely to make concessions with Russia, China, Iran and North Korea because they won't trust us.”

“We spend hundreds of billions of dollars [on defense] to establish the credibility of our extended deterrence,” said Joseph S. Nye Jr., a former dean of the Harvard Kennedy School who worked in the Clinton administration. “Trump creates doubts… that undermine those investments.”

Or take it from someone who worked alongside Trump during the first term: his former national security adviser, John Bolton.

“The damage he caused in his first term was repairable,” Bolton said recently. “The damage in the second term would be irreparable.”

After Biden won the 2020 election, he sought to assure U.S. allies that the four-year Trump era was a temporary anomaly.

“America is back,” Biden proclaimed.

If Trump wins a second term, the message will be: No, he is not.