An industrial chemical used in plastic products has been showing up in illegal drugs from California to Maine, a sudden and puzzling shift in the drug supply that has alarmed health researchers.

Its name is bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidyl) sebacate, commonly abbreviated as BTMPS. The chemical compound is used in plastics to protect them from ultraviolet rays, as well as for other commercial uses.

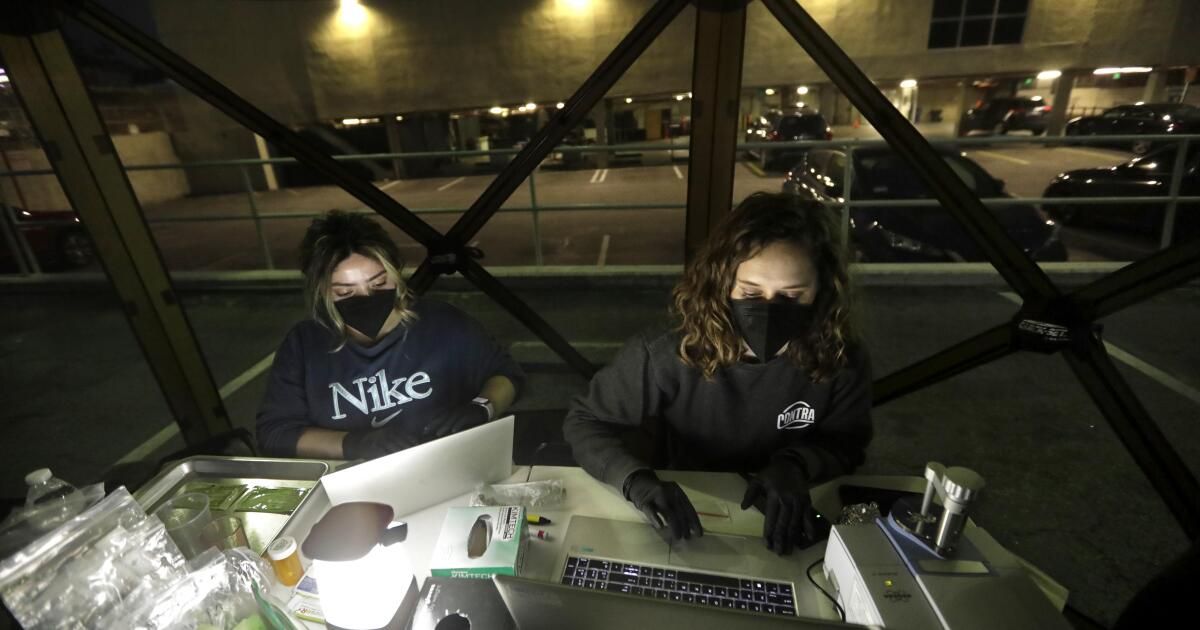

In an analysis published Monday, researchers from UCLA, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and other academic institutions and harm reduction groups collected and analyzed more than 170 samples of drugs that had been sold as fentanyl in Los Angeles and Philadelphia this summer. They found that about a quarter of the drugs contained BTMPS.

Researchers called it the most sudden shift in the illegal drug supply in the United States in recent history, based on the prevalence of chemicals. They found that BTMPS sometimes dramatically exceeded the amount of fentanyl in drug samples and in some cases had accounted for more than a third of the drug sample.

BTMPS was also found to be increasingly present in fentanyl over the summer: in June, none of the Los Angeles fentanyl samples the team analyzed contained BTMPS, according to the analysis. By August, it was detected in 41 percent of them.

“This is unprecedented,” said Morgan Godvin, one of the study’s authors and director of the Drug Checking Los Angeles project, a UCLA project that works in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to test for illicit drugs.

“We have no idea how many people have been exposed,” Godvin said, but if the high prevalence among drug samples analyzed so far is any indication, “that translates to tens of thousands of fentanyl users exposed to BTEMPS, sometimes in very high volume.”

The findings were published as a preprint (research that has not been peer-reviewed) on the Drug Checking Los Angeles website and submitted to medRxiv, a website where scientists share preliminary findings.

BTMPS has been studied in rats for its potential to reduce morphine withdrawal symptoms and affect nicotine use, but it can be toxic and even fatal to rodents in sufficient doses, and health researchers say there is an urgent need for more studies into its effects on the human body.

The PubChem database lists a number of potential dangers associated with BTMPS, including skin irritation and eye damage. Godvin was alarmed by animal studies indicating dangers from inhaling BTMPS (such as tremors and shortness of breath), because smoking is now common in Los Angeles among people who use fentanyl.

People who use drugs have said BTMPS can smell like insecticide or plastic and have reported blurred vision, nausea and coughing after ingesting it. One told researchers that it “smelled so bad I could barely smoke it.” The UCLA and NIST researchers warned that “with such sudden and sustained prevalence in the drug supply, users are at risk of repeated and ongoing exposures, which can exacerbate health effects.”

A 35-year-old Los Angeles man said he had noticed a rubbery or synthetic taste to the fentanyl he was using in recent months. “I asked my friend that I buy it from, ‘What the hell is this?’” said the man, who requested anonymity to discuss his drug use.

When he brought samples that were believed to be fentanyl to Drug Checking Los Angeles for testing, he learned that some contained the strange chemical. The 35-year-old said he now tries to avoid BTMPS, but “a lot of people are trying to get anything so they don’t get sick” from opioid withdrawal.

Whatever the clandestine labs are doing, he said, “we are the guinea pigs.”

Los Angeles and Philadelphia are far from the only places the chemical has turned up: The team also detected BTMPS in trace amounts of drugs left behind in drug paraphernalia from other locations, including Delaware, Maryland and Nevada.

By last week, a University of North Carolina program that tests drug samples from around the country had also found BTMPS in more than 200 samples from a dozen states stretching from the West Coast to Maine. UNC senior scientist Nabarun Dasgupta said the chemical began showing up in drug samples he tested this summer, most often mixed with fentanyl, both in powder form and in fake pills.

Alex Krotulski, director of the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, a nonprofit in Pennsylvania, said the amount of BTMPS found in drug samples he has analyzed varies dramatically — sometimes it constitutes a small amount, sometimes it constitutes the “primary component” of the sample.

Unlike other adulterants added to fentanyl for its psychoactive effects, “it’s not something you go out on the street and use in large quantities to get high,” Krotulski said. The UCLA and NIST team found that people who use drugs rated samples high in BTMPS as “junk” (low quality) and generally considered them “highly undesirable.”

Another oddity is that BTMPS has not followed a familiar path for new drugs in the U.S. Instead of appearing in one area and spreading to others, “this one has hit everyone at once in the U.S. in a two-week period,” said Tara Stamos-Buesig, founder and executive director of the San Diego Harm Reduction Coalition.

Stamos-Buesig, whose group helps analyze illegal drug content in San Diego to inform and protect people, said “I've been telling people for a while: We can't focus too much on fentanyl” as if it were the only threat.

“There are a lot of other things that are coming together,” Stamos-Buesig said.

The UCLA and NIST analysis suggested one possible scenario: Illegal drug manufacturers could be adding BTMPS to fentanyl precursors or the final product “at a high level in the supply chain,” possibly to stabilize them and prevent them from degrading from exposure to light or heat as the illicit drugs are manufactured, stored and transported, they wrote.

Chelsea Shover, an assistant professor at UCLA, added that the team had found BTMPS for sale on online platforms like Amazon and Alibaba with wording similar to that used by Chinese chemical companies in the past to market to fentanyl producers, with sellers touting their “experience in getting through Mexican customs.”

“This clearly implies that it is going to be used to manufacture illegal drugs,” Shover said. “It is a material that you would not expect to see if you were simply selling a standard industrial chemical.”

Currently, there is no test strip that can rapidly detect BTMPS like there is for fentanyl. Nor do doctors or coroners routinely test for the chemical, meaning that if someone was harmed by accidentally ingesting BTMPS, “clinicians would have no way of knowing,” the UCLA-NIST team wrote.

UNC’s Street Drug Analysis Lab also said there is still much to learn, including whether BTMPS poses an overdose risk, though the lab cautions that “ALL substances in some volume will be toxic.”

Dasgupta said the BTMPS detection represents the first example of the growing network of drug-checking programs working together to find a substance “before health authorities or law enforcement did.” Godvin said that “just a few years ago, we wouldn’t have even known about this” and urged Angelenos to get drugs tested through Drug Checking Los Angeles if they can.

In a drug supply already plagued by threats like fentanyl and the animal tranquilizer xylazine, “this gives us another thing to worry about,” Godvin said.