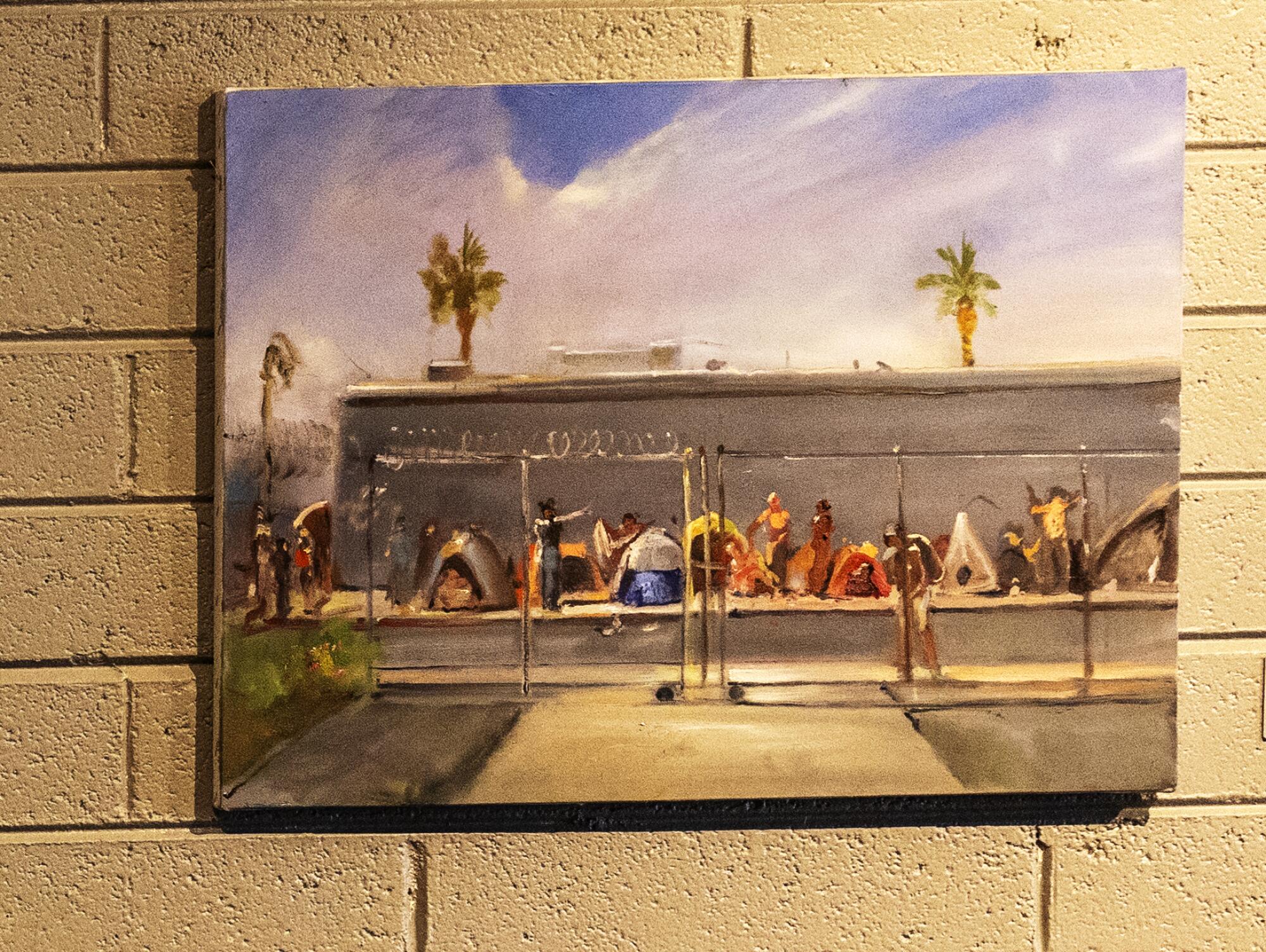

Artist Joel Coplin has spent the better part of three years painting what he sees through his studio window:

A woman showering with a hose next to barbed wire; a body lying motionless at an intersection under a streetlight.

A sample of Coplin's artwork.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Then there is an unfinished piece he calls “The Land of Nod,” a tribute to the men and women who seem to defy gravity while no longer suffering from the effects of opioids.

It's part of a complicated relationship Coplin has with Phoenix's homeless population, a mix of compassion and frustration.

He and his wife, fellow artist Jo-Ann Lowney, maintain a gallery in an area known as the Zone, about 15 square blocks on the edge of the city center that has been the fulcrum of the city's fighting over Homelessness policy. They live above the gallery and represent approximately half of the population housed in the area.

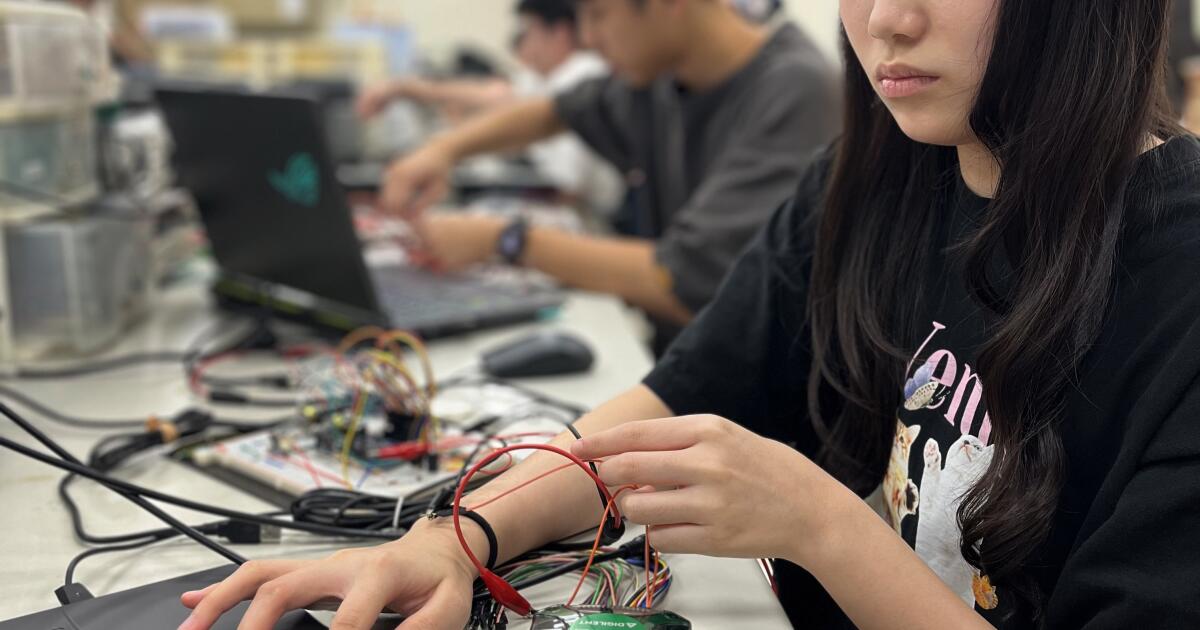

A painting by Coplin depicting a homeless encampment.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Coplin, 69, has helped homeless people with food, money and medical bills. He has paid them $20 to sit for portraits, tell their stories and listen to his.

But he was also punched in the face and had his glasses broken when he went to look for one of his homeless friends. And he has been a plaintiff in a lawsuit that forced the city to clear encampments that were once so prevalent that he couldn't open his downstairs gallery for two years.

Although the encampments have been removed from the Coplin neighborhood, homeless people still come in droves to receive services at the Key to Change campus, a block away.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“It just became this amazing barter town,” he said. “They built buildings out of tents that were about three deep and 50-gallon drums at night with flames coming out of them; You know, cooking, music, singing and dancing. “It was like an incredible street fair: 24/7.”

Coplin moved to the property six years ago after selling his former art studio east of town. He was cheap and liked the nervousness of the neighborhood. He had spent a decade in New York's Hell's Kitchen and had gotten used to “going over people and addicts and all that.”

People were sleeping on the street next to the gallery when he moved there, but they didn't have tents and left during the day, he said. He helped his neighbors buy things and let them use his bathroom, “like a little community.”

But after the federal appeals court decision restricted police's ability to clear encampments, people began handing out tents, he said. During the pandemic, they left again for about a year and then returned.

“So it's been kind of back and forth,” he said.

“Debbie on the street with her things” by Coplin.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

His art studio and gallery, Gallery 119, is near the Key Campus, a 13-acre complex that includes most of the city's homeless shelters and services. Otherwise it's a relatively deserted area, aside from her studio, a few warehouses, some old houses, a sandwich shop, a cemetery, and train tracks.

Coplin and other property owners sued the city and obtained a court order to remove the hundreds of people from the Zone in November. Homeless people still roam the area, but there are no longer groups of tents.

Conditions are better, but the city still has the wrong solution for homeless people, he said: There should be smaller, more specialized shelters throughout the city, instead of a single five-block super campus.

Amy Schwabenlender, executive director of Keys to Change, the organization that oversees the campus, said cleaning up the area has brought more people to campus, especially during the day. At night it's another story.

“But we still can't house everyone, so we know that X number of people leave every night and sleep somewhere,” Schwabenlender said. “It's not necessarily safe, it's not intended for human habitation.”

As a Beethoven symphony plays in the background in Coplin's studio, it's hard to imagine the outside devastation that inspires his paintings. He remembers the night he looked out his window and saw what he thought was an object “right in the middle of 11th Avenue and Madison.”

Coplin in his home studio.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Then he saw movement: “a person!” The cars zigzagged but did not stop. She ran down to help. But before he got there, someone else arrived and a simple touch startled the person.

“He jumped up and started running,” he said. “I said, 'Oh my God, that's Elizabeth.' “I met her.”

Coplin's portraits have a quiet dignity: a man in a three-piece suit; a woman looking up as she holds her dog, whose only protection is a rain blanket.

Coplin’s portraits have a quiet dignity, including “Soaked,” above.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

He also looks to the past for inspiration. In a group scene, eight people are bent over to resemble characters from Diego Velázquez's 17th-century play known as “Los Borrachos” or “The Drunkards.”

He pointed to a historic library down the street that is now empty. She is campaigning to turn it into a museum for the state's artists. She remains hopeful that the area can become a place where people come to buy her art and appreciate the potential she sees.

“This is the final frontier,” he said. “Every other aspect of downtown has been taken over.”

He has always rejected the idea of gentrification, “but now I am at the other extreme and I want gentrification. And I want condos.”

Recently, someone called him to offer him $940,000 for his property, he said. He told them no.