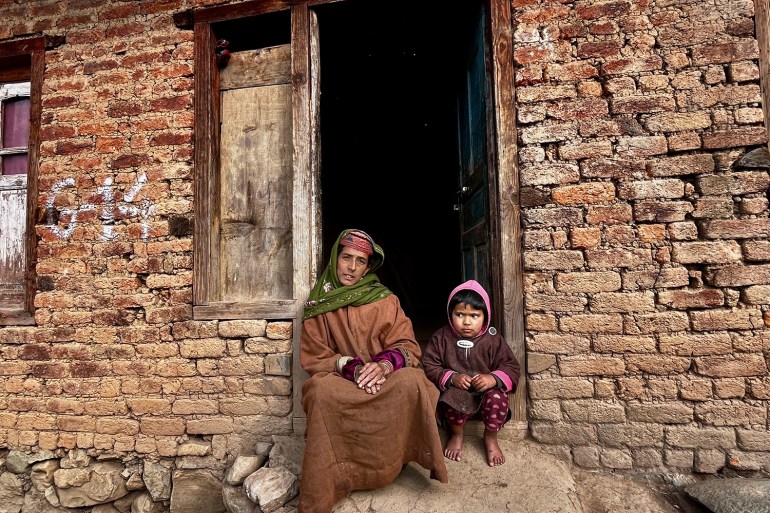

Tral, Indian-administered Kashmir – Like many people in his nomadic tribal community, Bashir Ahmed Gujjar, a 70-year-old shepherd, never went to school.

Poor and often on the move, formal education was not an option.

Things changed for the Gujjars, their community, after the government introduced quotas for what in India are known as Scheduled Tribes (STs), in state educational institutions and government jobs in 1991 as part of an affirmative action program for groups. historically marginalized. Gujjars were included among the beneficiaries.

Families decided to send their children to school and university. “My children, my nieces and nephews have been fortunate to have been educated thanks to the ST status granted to us by the government,” Bashir told Al Jazeera at his home in the region's Pulwama district. He said his niece now works as a teacher in a government school in Tral due to job quotas that Gujjars can avail.

Now he fears that the next generation of his community could lose the achievements of the last three decades.

Earlier this month, on February 6, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government passed a legal amendment to include another community, the Paharis, under the ST list. At the time, federal Tribal Affairs Minister Arjun Munda said the law would not erode the education and employment quotas currently available to existing tribes, but would add additional quotas for new communities.

But the government has not yet explained how it plans to do so, raising fears among Gujjars and Bakarwals, two important tribal communities originally covered by affirmative action, that they will now have to split its benefits with Paharis, who have historically been seen as in a better situation.

“We have no hope for the future. The government is giving our share of guarantees to others,” Bashir said.

The government's move has sparked a wave of protests by Gujjar and Bakerwal community groups, demanding that the amendment be repealed. The move has also sparked caste divisions in a region that was already on the brink of other controversial moves by the Modi government in recent years.

The decision to add Paharis to the ST list could affect the national elections, scheduled between March and May.

'Using reservation to influence Paharis'

The Paharis are made up of Hindus and Sikhs (who mostly emigrated from what is now Pakistan when the subcontinent was divided during partition in 1947) and a significant number of Muslims.

Nearly two-thirds of the Paharis, who make up about 8 percent of the region's 16 million people, live in the Jammu area towards the south of Indian-administered Kashmir, while a few reside in the forests of the north.

The current tensions have their origins in the events of 2019 when, in a sudden move, Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government abolished the region's special status and brought it under direct rule from New Delhi.

Since then, the Gujjars and Bakarwals allege that the BJP has been trying to include the Paharis in the ST category.

India's affirmative action to uplift its historically marginalized groups – mainly scheduled castes and indigenous tribes – also includes a provision to reserve seats for them in legislative assemblies.

In Indian-administered Kashmir, also called Jammu and Kashmir in official documents, seats in the state assembly were reserved in 2004 for the Gujjar and Bakarwal communities.

Members of these two communities – who constitute around 10 per cent of the region's population – now allege that the BJP is trying to patronize the Paharis community for political gains ahead of the general elections.

More than 200 kilometers from Tral in Jammu, Javid Chohan, another Gujjar, said the government was trying to curb the protests through increased police presence and internet shutdowns.

“The BJP is using reservation to influence the Pahari-speaking population of the region and strengthen its Hindu vote bank in Jammu,” he told Al Jazeera. Unlike the Paharis, the Gujjars and Bakarwals of the region are predominantly Muslim.

Pro-India political parties also allege that the BJP is using the community to sell its politics, as it did with its promise in its 2014 and 2019 election manifestos to resettle thousands of Kashmiri Hindus, called Pandits, displaced by the rise of an anti-India group. Indian rebel movement in the late 1980s.

“First, they used Kashmiri Pandits to win the 2019 elections. This time, the Paharis are being politicized. The BJP is pitting communities that have lived in harmony for centuries against each other,” Waheed Ur Rehman Para of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) told Al Jazeera. “They are stealing from one person's plate to feed the other.”

Naik Alam, elected representative of Gutroo village in Tral, said the BJP was “simply misusing” the law to show that Hindus can also get reservation in a Muslim-majority region.

What is the BJP's electoral plan?

In Indian-administered Kashmir's 90-member legislative assembly, the BJP, which relies predominantly on Hindu votes, has traditionally performed well in the Jammu region, where Hindus are in the majority. But it has struggled to make political progress in the Kashmir region, where Muslims are in the majority.

Spanning Jammu and Kashmir there are nine seats in the legislature reserved for STs. BJP critics argue that winning them could help it secure an overall majority in the legislature: state assembly elections are also expected to be held later this year.

In 2020, the federal government granted 4 per cent reservation, as a linguistic minority, to Paharis, who form the majority in at least 10 constituencies. If granted ST status, the group could contest the seats reserved for STs in the legislature and challenge the traditional dominance of Gujjars and Bakarwals in these outfits. Gujjars and Bakarwals are predominantly Muslim and rarely vote for the BJP.

Gujjar activist Guftar Ahmed Choudhary said the BJP's move would be counterproductive.

“We are protesting for our rights. Our youth leaders are being attacked and even pressured by the authorities to leave the movement… This is completely unconstitutional and the BJP will suffer in the upcoming elections,” Choudhary told Al Jazeera.

But according to the BJP's former deputy chief minister of the region, Kavinder Gupta, reservations towards the Paharis were long overdue. He alleged that Kashmiri political parties considered the community as second-class citizens and ignored their development.

“We were just trying to bring paharis into the mainstream as they have always been marginalized by Kashmiris,” Gupta told Al Jazeera.

Lawyer Ahsan Mirza, a member of the Pahari Tribe ST Forum, a group working for the welfare of Paharis, said the BJP had earlier assured the community a place in the tribal quota.

Iqbal Hussain Shah, another Pahari activist in Rajouri's Jammu district, echoed Gupta's comments by arguing that Paharis were discriminated against for decades. He also suggested that even Muslim paharis would now support the BJP, a Hindu-majority party.

“Gujjars and Bakerwals got ST status in 1991 and the BJP finally got it to us after three decades. All paharis will definitely support the BJP in the upcoming elections,” he said.

But Zahid Parwaz Choudhary, director of the Gujjar-Bakarwal Youth Welfare Conference, sees a more sinister plan on the part of the BJP.

“Now that Paharis are declared STs, the community will take advantage of opportunities aimed at social and economic empowerment of Gujjars and Bakarwals,” he told Al Jazeera.

“It's simple: the BJP knows that it cannot get many votes in Kashmir, so they are using the Paharis to cut into the vote share of other political parties.”