Word spread that there was a whistleblower who wanted to meet. The company was suspicious, but this was the first overt warning that our workplace was corrupt. Should we investigate and see what ethics are being violated, or play dumb and remain loyal to the company? We were divided.

I wanted to connect with the insider: If something is wrong, we should know about it, even if it jeopardizes our rapidly growing career. But wasn't that typical of the avatar we had chosen?

This is the Hatch Escapes Staircase, an interactive experience near Koreatown that explores corporate corruption. It opened this month and has become one of the most talked about escape rooms in the country.

In 2018, Hatch Escapes debuted a highly regarded escape room in Lab Rat, a horror comedy show in which the roles of humans and test rodents are reversed. It's a 60-minute game, with puzzles, an ending and, of course, a quest to free yourself. While it won praise for its combination of digital and analog media, as well as its emphasis on storytelling, Lab Rat remains what many of us understand an escape room to entail.

The fictional Nutricorp is the center of Ladder, a complex and branching narrative that explores corporate greed.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Its sequel, Ladder, is not that.

For the past five years, Hatch Escapes of Los Angeles has been rethinking the basic rules of escape rooms. The goal: to demonstrate that an escape room is not mere entertainment, but can in fact be experienced as a piece of narrative art.

Think of Ladder as a 90-minute interactive puzzle movie, taking visitors through five decades, starting in the 1950s, where they will play an exaggerated game of corporate life. Start in the mailroom and progress through secretarial and middle management themed areas, while mixing puzzles, games and choose-your-own-adventure options.

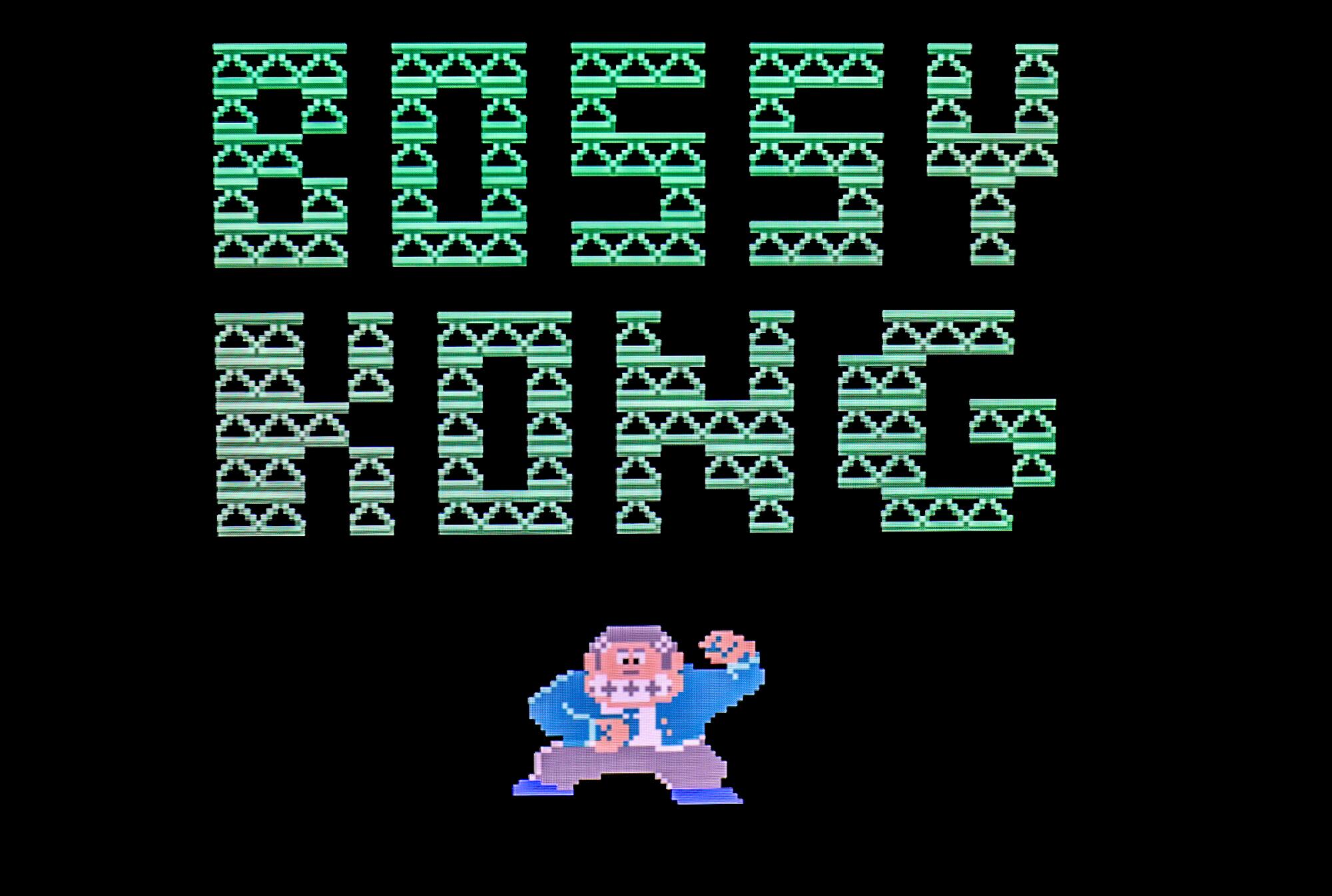

You may find yourself playing a memory game with digitally enhanced cocktail glasses, as our mid-level executive seemed more interested in the benefits of company cards than evenings with the books. Or maybe you choose to investigate a telephone exchange that takes up an entire wall, listen to callers' problems, and try to connect them with a solution. Elsewhere, in an area dedicated to the 1980s, Nintendo's “Donkey Kong” is remixed as “Bossy Kong,” with a suited villain instead of a gorilla trying to thwart our progress. The final room, the corner office, is a group gaming chaos inspired by the popular collaborative video game “Spaceteam,” with fully animated windows overlooking a city.

The fact that it incorporates a wide variety of games, puzzles, as well as films and animation, all designed to advance a story, has made this escape room one that is redefining the medium.

The title screen of “Bossy Kong,” an 80s-themed video game on The Ladder.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Tommy Wallach plays “Bossy Kong.”

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

“The Ladder, in terms of North American escape rooms, is definitely one of the five most anticipated games at the moment, probably in the top two or three,” said David Spira, co-founder of Room Escape Artist, a website dedicated to the art. of doing puzzles. “It's probably the most ambitious escape room I've ever seen, narrative-wise.”

If all goes as planned, ingenuity will be tested, but also morale, as participants will be judged on their puzzle-solving acumen and personal decisions. Play ethically, corruptly, or spend your time playing the putt-putt-turned-shuffleboard floor in a middle management office; The Ladder offers a large number of options, so many that it is impossible to discover all its content in a single game. It's ambitious, counting on guests coming to solve the puzzles and staying to watch the story, almost aiming to be more like a real-life video game than a traditional escape room.

“We wanted to create something that basically allowed a group of 10 people to never stop doing something effective,” says Tommy Wallach, co-founder of Hatch Escapes with Terry Pettigrew-Rolapp.

Its puzzles and games are all optional. And before it begins, guests will likely get a warning: The Ladder's puzzles are difficult.

Then it's time to turn a doorknob, which will activate one of the Ladder's multiple digital screens and ask groups to choose a character to portray; my team opted for a young narcissist who seemed eager to betray. However, we were not true to his temperament and often chose to follow the company line rather than align ourselves with unlikable actors. Story moments, in which all games and puzzles will be paused, are conveyed through screens. Think of them as video game cutscenes, that is, cinematic instances where players can give up control.

We discover hidden rooms (at one point, a wall will essentially disappear to reveal a film noir scene involving a subplot with the FBI, though only if a group solves a particular puzzle) and try out a host of digitally enhanced games. , some of which use lighting cues to remake a room. You'll definitely want to approach Ladder as if it were a playable movie, as a 1950s mailroom, for example, is presented in black and white, playing tricks with color and grayscale. While we rose through the ranks of the company, our ending (there are several, as you don't win or lose, per se) didn't make us the next billionaire; We lived a more solitary life, with a cat.

Designers Tommy Wallach and Terry Pettigrew-Rolapp at Douchie's Bar, inside a '70s-themed Ladder room.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

After extensive play testing, Ladder launched in early April. Wallach and Pettigrew-Rolapp are already in reflective mode. Each room (decade) features a central puzzle, which is directly related to the narrative, as well as a large number of mini-games. After about 15 to 20 minutes, guests will move on, whether they have solved the puzzle or not.

Wallach and Pettigrew-Rolapp wonder if the team went too far with the narrative. Will players follow the plot or choose to simply play? And with so much to do in each decade, will guests want to come back to do more or will they feel overwhelmed?

“Our initial idea was that we were trying to advance this art form,” Wallach says. “We're doing that with this room, although not necessarily exactly the way we thought we would. We thought we were going to try to get into a more serious narrative or better: more involved characters. I don't think that's what the Ladder achieves. What it does do is try to solve some other escape room problems. Replayability is one of them. Can we create something that people want to come back to the same way people want to come back to Disneyland, because it's not solved or done?

It's surprising to hear Wallach say that Ladder may not achieve all of its narrative goals. After all, storytelling is what helped build Hatch Escapes' reputation. In addition to Lab Rat, the company created “Mother of Frankenstein,” which is part novel and part puzzle board game. Hatch is also home to the live-action exploratory game created by Scout Expedition, “The Nest,” a patient, interactive narrative in which participants discover a woman's life story.

“When they launched Lab Rat, it was the kind of game that their reputation preceded them across the country,” said New Jersey-based Room Escape artist Spira. “We knew we had to return to Los Angeles to play that game. “It was pushing a lot of boundaries that very few people were able to do: they were pushing the narrative and incorporating messages into the game.”

While one could simply play Ladder and skip much of the story, doing so would mean missing out on many of the nuances of the experience. Puzzles, for example, build on each other, and characters from a board game, which contains more than 100 clues, may later appear in another challenge, perhaps one in which an ancient computer coldly orders us to reduce the corporation's staff. But Ladder raises an intriguing question: do puzzle game fans really want more stories?

Tommy Wallach shows off an escape room puzzle located in Ladder.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

It is, Wallach admits, difficult to achieve. Guests coming to play, for example, may not be prepared to watch multiple videos that advance a plot.

“The canvas is very small. You have very little time to develop characters. Getting people to stop and listen to a story is almost impossible,” says Wallach. “I empathize, but you can't tell a better story unless you give me space to tell you a story. That balance is more difficult than expected.”

And Ladder is counting on players wanting to experience a little story with the game. Part of the reason it took five years to build is that the Staircase is custom-made and cost more than a million dollars to complete. It's a premium escape room experience, with per-player costs typically ranging between $75 and $95, depending on the day. “Everything is custom-made,” says Pettigrew-Rolapp. “There is literally nothing available. The scale of what we are trying to achieve requires it and there are no experts in this. “Every person who worked on this had to learn as they went, because no one had done this before.”

It's early, but The Ladder is finding its audience. It has been heavily selling out about two weeks in advance as of this writing. Wallach appears optimistic and confident.

He believes the adventure will continue to peter out. “It needs to run out, but it will,” he said. “I really think that's how it will be,” Wallach says. “We see maybe a tenth a week of what a Broadway theater sees in a day, and those tickets are $200 per person and not $95. But we're going to need a couple of good years before we say, 'Everything is wonderful again.' “

Hatch is already attracting national attention for delivering a boundary-pushing experience. It's a winning start and probably means the only company that's ruined is the fictional one at the heart of Ladder.