I knew The Morrison Game Factory had me hooked when I started responding. There I was, home alone, chatting with a fictional machine.

There were puzzles scattered around me: colorful dice, a small board, tiny plastic rockets and a stack of cards with seemingly unconnected pictures — a golfer, a mushroom, a diver and more. I had spent about two hours playing Lauren Bello’s puzzle game, but I was devouring it more as a story. That’s because “The Morrison Game Factory” plays out like an interactive narrative, with each challenge unlocking another mini-chapter in a tale of friendship, loneliness and even grief.

There were times when puzzles stumped me. I used the hint system on one that involved numbers. But more often I stopped to reflect, struck by a poignant line. One example: “I like that talking to me isn’t work for him,” an observation about what it feels like to be in true conversation and connection with someone. It certainly wasn’t what I expected when I opened a fascinating box with a vintage feel detailing a fantastical assembly line and saw a handful of board game figurines. Later, I felt an urgency to complete the game, especially once the relationship at its core is severed.

Lauren Bello’s game, “The Morrison Game Factory”.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

That’s when I wanted to communicate with the main character of “The Morrison Game Factory.” I sat, deep in contemplation, reflecting on the times in my life when I had to deal with separation and heartbreak. Such is the power of Bello’s tabletop puzzle tale. Yet there was no time to think. Within seconds I was back in action, arranging little wooden people (meeples, as they are known) around a pinwheel with numbers at the end of each spoke. There were puzzles to solve and a story of loneliness to heal.

Bello’s “The Morrison Game Factory” was one of the best stories I encountered (or played) this summer. Bello, a Los Angeles-based TV writer who has written for series like “Foundation” and “The Sandman,” began creating the game for friends during the worst days of the pandemic. It’s a love letter to play as a form of communication, a treatise on how games can connect us and allow for vulnerability in our relationships. It’s also a hopeful statement, one of moving forward with gratitude rather than sadness, and how every day can be filled with a new playful discovery.

“I think grief can be so intense that you can’t look directly at it because you’d go blind,” says Bello, 36. “Games, fiction and other forms of media can be a way to process your grief and overwhelming feelings in the background without forcing yourself to look directly at them. If done well, you realize that you and your grief are side by side and holding hands, and you realize, ‘Now I can turn around and look at your face. ’”

Exploring “The Morrison Game Factory” is a joy. The concept: We’re handed a box of board game pieces that had been lost, all of them, we’re told, salvaged from an abandoned game factory and seemingly connected. The game is a constant act of discovery: Maintenance logs will lead us to a website, where we’ll meet characters who once worked at the now-defunct game warehouse. We’ll be asked to look at crossroads puzzles in unexpected ways, piece together visual obstacles, build actual puzzles, and take part in a task that feels like a mini science experiment.

We are given numbers to call and occasionally read the innermost thoughts of the main character, who, as we learn through the opening puzzle, is a machine that has been able to gain the gifts of human thought and compassion. Bello's slight inclination toward science fiction came naturally to him.

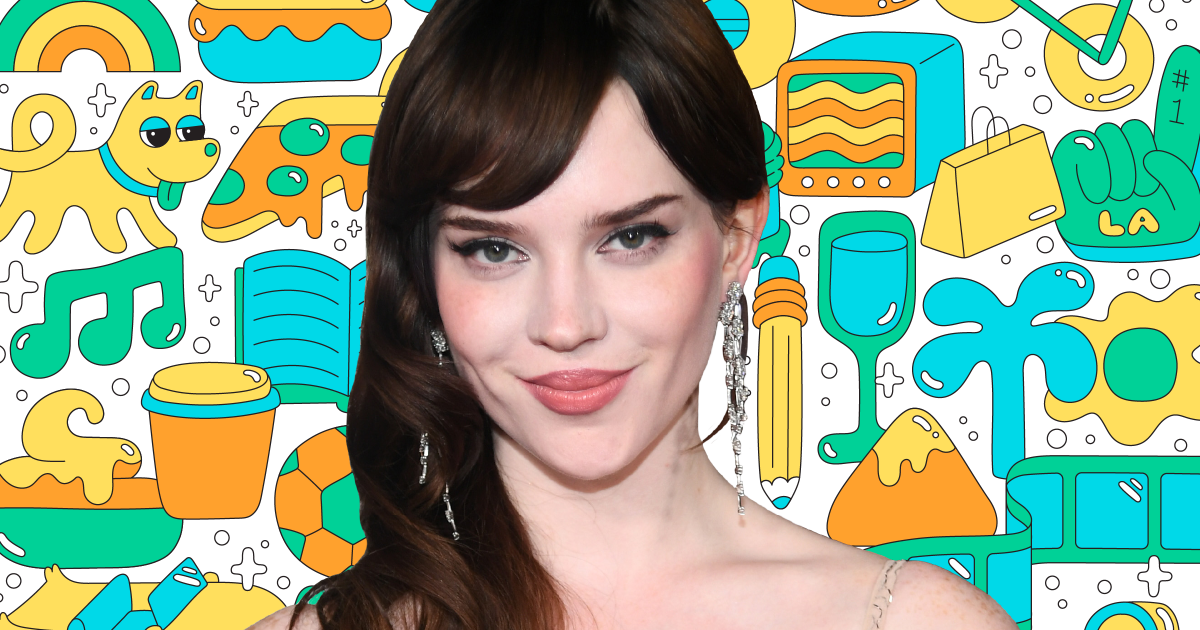

Lauren Bello, a Los Angeles-based television writer, with her game, “The Morrison Game Factory.”

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

“I’m definitely drawn to genre,” Bello says. “I feel like the world is changing so quickly – the way people talk, the way people act, the things people have access to. Genre is a fun way to say what you need to say while also protecting yourself from the effects of time.”

What would become “The Morrison Game Factory” began as a holiday exchange for a Facebook group of puzzle enthusiasts. Bello’s game attracted attention and eventually found its way into the hands of Rita Orlov, whose Bay Area company, PostCurious, would publish the title. “When I played it, I fell in love with the range of emotions I felt while experiencing the narrative: It made me laugh, it made me feel sadness and empathy, and it made me genuinely care for the main character, all of which seems like a rarity in board games,” Orlov says.

“The Morrison Game Factory” reorients us to search for a story rather than a solution, which means we can sometimes make the puzzle harder than it actually is. I played solo, even though up to three are recommended, and sometimes wished I had someone to bounce ideas off of. That’s because sometimes the answer is just hidden in a catalog description. In that sense, figuring out what the puzzles are asking us to do is sometimes a bigger challenge than the puzzle itself, but the underlying narrative drive helps create a sense of urgency.

“The Morrison Game Factory” is a constant act of discovery set in a now-defunct game warehouse.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Bello says writing for television helped her set the stage for the game, especially when it came to building tension.

“I think ‘Morrison Game Factory’ naturally fell into three acts,” Bello says. “My experience writing other kinds of stories told me what those acts were. Also, good stories control a flow of energy. They have a very intentional sense of momentum. In the game I tried to start off easy and with expected momentum, and then build up the energy. By the third act, you feel like you’re on a roll. I’m on fire. The puzzles get a little shorter, and you start to feel like everything that came before is now taking shape. That’s a skill I learned from other writers.”

Still, the fact that the game is reaching a wider audience has Bello reconsidering some of his approach. “The Morrison Game Factory” began with a Kickstarter campaign and quickly surpassed its $30,000 goal in just a few hours. (PostCurious has a strong following in the board game world for its narrative-driven games, particularly the tarot-inspired “The Light in the Mist.”) Reviews beyond the board game world, in escape room and immersive communities, have been positive, praising the title as an accessible, emotional game that prioritizes story — with some even questioning whether it’s possible for a board game to make you cry.

“The magic trick of The Morrison Game Factory is that you don’t think about the puzzles. You want to solve them not for the sake of the puzzles themselves, but for the sake of the character and the story,” says Lisa Spira, co-founder of Room Escape Artist, a site dedicated to the escape room industry.

Bello wonders today whether the initial puzzle — a cipher challenge — might overwhelm some of those new to the space. “I try not to waste people’s time unnecessarily,” he says. “Sometimes it’s easy to turn things into a puzzle. I always try to focus more on the experience. For example, will having this puzzle enhance your experience? Will there be a moment of revelation or delight, or will it lead to, ‘Cool, now I have to put a lot of work into this puzzle.’”

Lauren Bello’s “The Morrison Game Factory” unfolds as an interactive narrative, with each challenge unlocking another mini-chapter in a story of friendship, loneliness, and even grief.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

And yet the game is relatively forgiving. When we are led to the accompanying website, a robust hint system delicately reveals solutions. The goal here is fun – games as dialogue, which play out as we emotionally heal the story’s protagonist.

“I played a lot of games with my family, and I loved the way games could become a way to express things,” Bello says. “I loved when one person could place a piece and everyone would go, ‘Ohhh.’ You immediately knew what they were doing. There was a whole unspoken language behind the movement of the pieces. You could be expressing loyalty to someone or confronting someone, and it was a whole different world of language.”

Experiencing “The Morrison Game Factory” is basically having a conversation, one in which we learn a dialect centered on the game. And it turns out it’s a dialect that serves a lot more purpose than just offering a challenge.

“At the end of the day,” Bello says, “it’s used to express love. That’s what it is to me.”