A few minutes into the play, the actors stop, empty their pockets, and repeat their final lines. And then they do it again. And again. And again. This live approximation of a vinyl record on repeat continues for a few more minutes, the actors getting a little louder and a little more irritable as they continue the reprise.

They can't move, they say, because they are “waiting for Godot,” but in reality they are waiting for us, the audience, to get up from our seats, walk onto the stage, and start putting together a puzzle from the pieces of paper they have dropped.

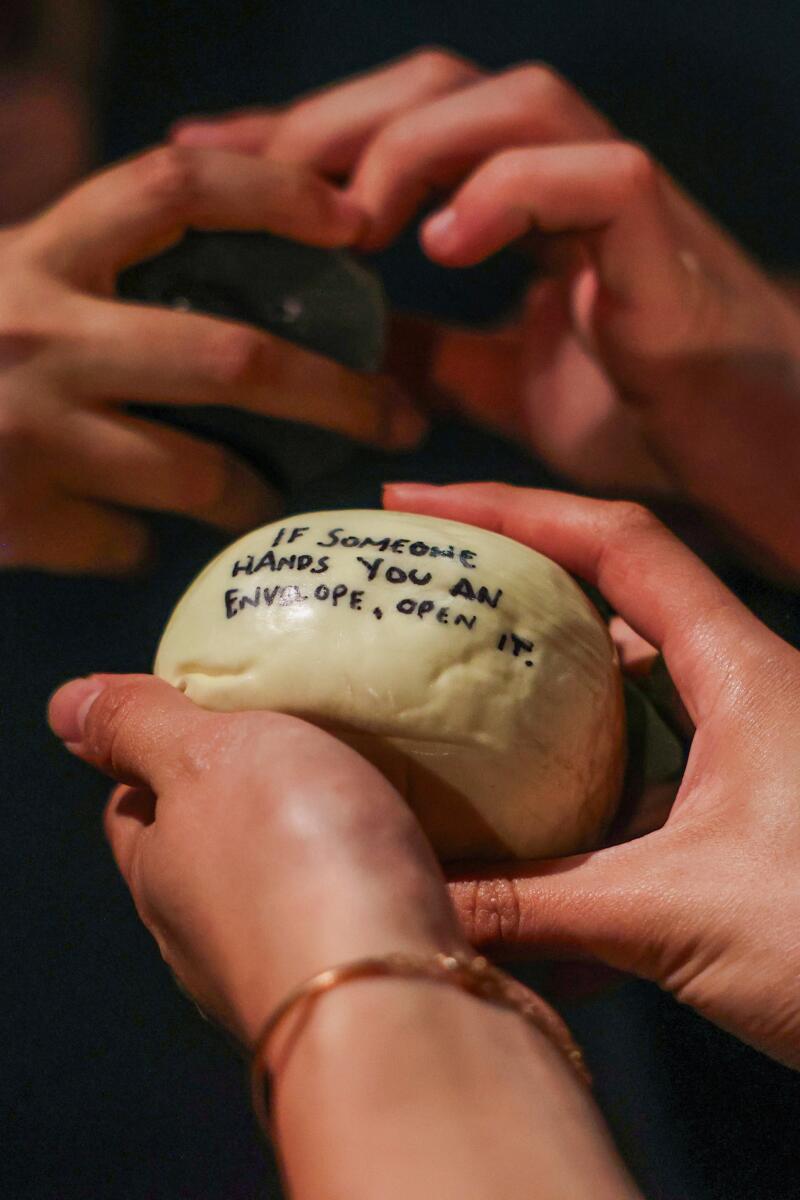

There were cards and letters on the floor for viewers to figure out the next clue.

Melanie Pentecost holds a rock that gives the next context clue to move the play forward.

This is “Escape From Godot,” an escape room that is also a play, or vice versa. It subverts the conventions of both. It is a play in which audience members become participants, and the game requires spectators to step onto dials and interact with props to drive the narrative. Puzzles are hidden in the script, ensuring that players become actors and are in abstract communication with the performers.

But what’s its biggest trick? Inspired by Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” the theatrical escape room taps into the original play’s themes, creating an interactive, playful piece of art open to interpretation that addresses existential questions: how we communicate (or don’t) with others, and the balance between selfish behavior, free will, and empathy. Much like in Beckett’s play, there’s no Godot to come, but we’re all trapped in a world where the mundane, the absurd, and our own desire for answers propel us forward.

Our group (I’m playing with seven strangers) hesitates to jump onstage and get the game underway. It’s a breach of decorum, both of theater protocol and personal boundaries. One player nervously scans his ticket, trying to find a missing clue, another flips through a notebook placed on his chair, and most of us look at each other and whisper questions about what to do. Realizing, after about seven minutes, that there will be no end to “Escape From Godot” if we don’t move, my group hesitantly begins to work together. In order for the actors to move on to the next scene, we need to deliver a message crafted from the ephemera they’ve dropped.

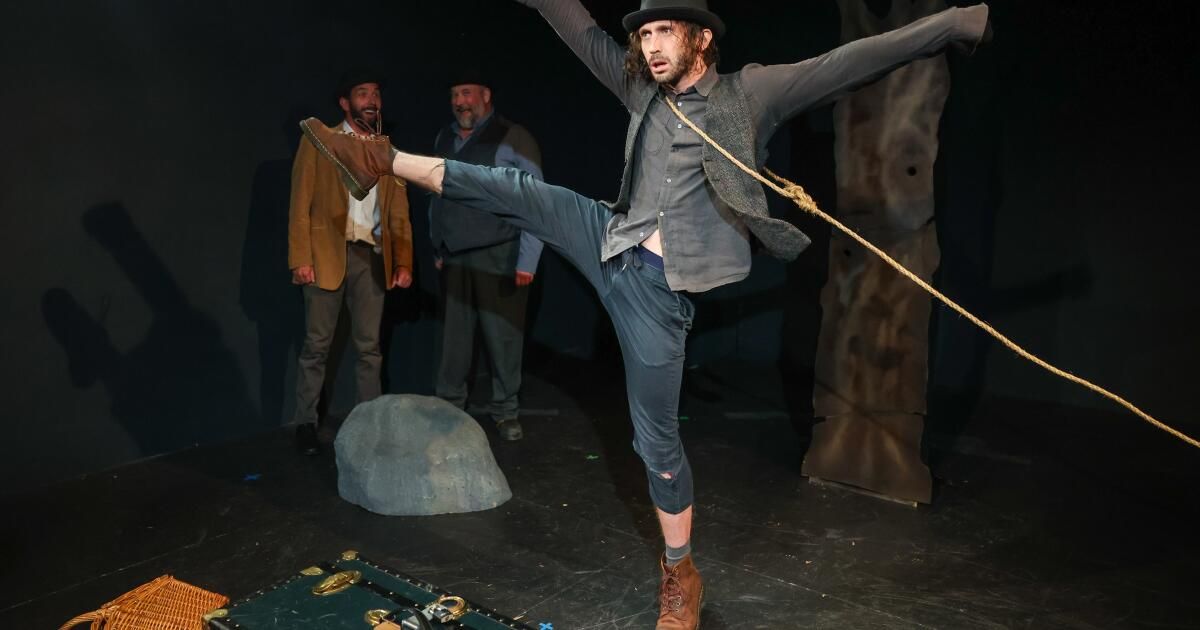

Actor Phil Daddario kicks the air during his performance.

Daddario wipes sweat from his face as he performs.

Audience members look at the floor for context clues to solve the next puzzle.

“I bet you’re not the group that’s been sitting the longest,” the show’s co-creator, Jeff Crocker, tells me later when I describe those seven minutes of awkwardness. Jeff is one half of Mister & Mischief, a husband-and-wife duo based in Los Angeles who have created experiences for theme parks, zoos, museums and more. (Jeff’s wife, Andy Crocker, recently created a game-like experience for the Los Angeles Public Library system.) “Escape From Godot” is their first escape room.

“Normally, people in theater, the last thing they’re going to do is get on stage in the middle of a scene,” Jeff says. “It’s a hidden conundrum. Are you the brave enough person to get on stage in the middle of a performance to stop this repetition? There are a lot of weird little social details like that.”

“Escape From Godot” premiered at the Hollywood Fringe Festival in 2018 and has been periodically rerun over the years, most recently as part of this month’s RECON event at the Universal City Hilton, a convention hosted by the escape room hobbyist site Room Escape Artist. Initial runs through Aug. 25 at Atwater’s Moving Arts Theatre sold out, so “Escape From Godot” has been extended through Sept. 8.

The idea came about when Crocker heard about an escape room in Europe that had been held on a train, a promotional event tied to a movie. Joking about possible properties on which they could base a project, the Crockers settled on “Waiting for Godot.”

“Andy has a degree in theater, and Waiting for Godot is classically known as a play where nothing happens,” Jeff says. “To people who don’t do theater, that’s a B-word — boring. It’s a play where everyone comes to wait for a person who never shows up. There’s more to it than that, and when you see a mediocre production of Waiting for Godot, you can feel like you want to run away. I’ve seen really good productions of the play, and there’s a reason it’s a classic.”

In “Escape From Godot,” the puzzles may be hidden in the actors’ bowler hats. Do we ask them to hand over their clothes or wait in the hope that they will drop them?

Actor Mason Conrad holds a large suitcase while acting in “Escape from Godot.”

Actor Justin Okin scans the play's script for lines that give viewers context for the next clue.

As in Beckett's play, characters in dubious physical shape appear on stage, but any feeling of compassion is soon overtaken by the desire to solve the next puzzle with the objects they carry. Boxes and baskets with padlocks can be dropped on stage, the combinations to which are found in the actors' monologues: Justin Okin as GiGi and Bill Salyers as DoDo, doubles of Vladimir and Estragon, played by Beckett.

“Escape From Godot” will even reference other plays. My favorite puzzle turned out to be a combination lock attached to a basket, where to figure out the solution we had to listen to a monologue alluding to famous cats from history and culture. “Escape From Godot” doesn’t even begin unless guests solve an initial puzzle, which requires us to line up our tickets with a theater seating chart and find the right seat. One could choose not to play, while others do, and sit back and watch, absorbing a script that plays with our place and faith in the world, albeit with a reference to the musical “Cats.”

The longer the audience waits without finding the right solution, the louder and faster the monologues become. This creates tension and tests the group's ability to remain calm and patient. Nothing becomes too complicated; the silliness of the situation dominates the tone.

The cast of “Escape from Godot” applaud the audience at the end of the play, including, from left, Tiffany Ogburn, Phil Daddario, Mason Conrad, Bill Salyers and Justin Okin.

“We set out to live up to our original, charming idea of having fun by escaping a notoriously monotonous play, but in doing so, as we started to develop what the puzzles were and how we wanted the audience to interact, we started to support the themes of the play while also poking fun at it a little bit,” Jeff says. “You get the little details of what Beckett was trying to say about what existence wants to be, what belief in God wants to be, but doing it in a way that’s mischievous.”

By the time the show is over, the roles have been reversed. Audience members have been cast as performers, and the actors have sometimes become the audience, caught up in repeating dramatic sentences as they watch us perform. It is a final message that is not too divorced from Beckett’s text: we are all performers, too often waiting for a cue.