The president was Eisenhower. The Dodgers belonged to Brooklyn. The cost of a round-trip flight between Los Angeles and London was $720, a staggering amount in 1956. However, in his spare hours, a young Manhattan lawyer named Arthur Frommer pursued a wild idea.

A few years earlier, as a U.S. Army soldier in postwar Europe, Frommer had seen the wonders of the continent and the purchasing power of a dollar abroad. He realized that many Americans could do the same, if they knew where to go and how to save money. He came up with the idea for a guide, tested it by publishing a brochure for military personnel overseas, and quickly sold every copy.

Then Frommer attempted an even bolder coup. In 1957, he published “Europe on Five Dollars a Day” and ushered in a new era in travel, persuading legions of middle-class Americans that the art, architecture and cuisine of London, Paris and Rome were not just for the aristocrats.

The first money-saving rule decreed in that guide: “Never specify that you want a private bathroom with your hotel room.”

As advances in technology and deregulation reduced the cost of transatlantic flights in the years and decades that followed, Frommer's words found a growing audience. In 1961 he had left the law to devote himself full-time to writing about affordable travel. In 1962, he hired other writers to produce guides such as “Los Angeles, San Francisco and Las Vegas for $5 and $10 a Day.”

“I held on to the '5 dollars' [in the book’s title] until about 1964,” Frommer once told me. “I remember the first year I had to change it to $10, I was overcome with the most horrible feeling of dread. … I thought, 'Well, that's the end.'”

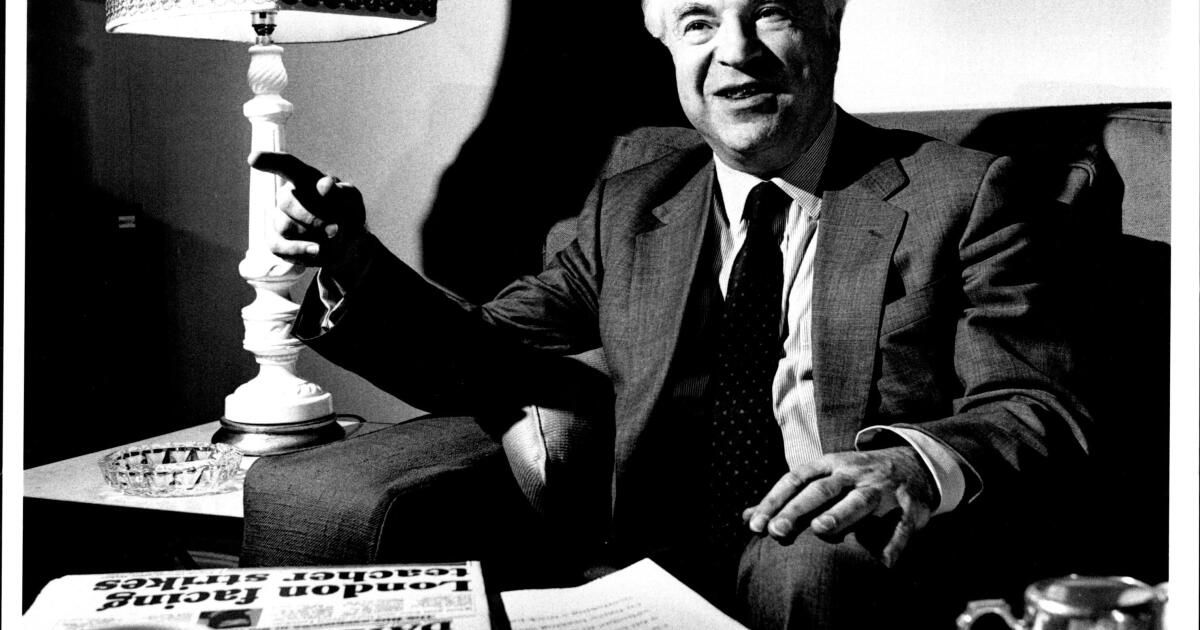

Nothing of the sort. Before his death at his home in New York on Monday at age 95, Frommer built and sold a tour guide empire, ran a travel company, created and sold a magazine, started a travel website, a radio show and a podcast, bought back his guide empire and tutored generations. of travelers and travel writers.

Without Frommer's pioneering work, it's hard to imagine the Lonely Planet guidebooks (founded by Tony and Maureen Wheeler in 1973) or the career of Rick Steves, the professor-turned-editor-turned-public-television figure whose first edition of “Europe through the back door” “It came out in 1980.

“Arthur's work gave people like my parents the confidence to travel independently in Europe when that was new for middle-class Americans,” Steves wrote in a 2013 blog post. “One could argue that if Arthur “Frommer didn't open that door to my family in 1969, I'd still be giving piano lessons.”

Arthur Frommer, right, and his daughter, Pauline Frommer, photographed in New York in 2007.

(Jim Cooper/Associated Press)

Frommer's partner in much of this work has been his daughter Pauline, co-president of FrommerMedia and editorial director of Frommer's Guidebooks. Throughout his life, Pauline Frommer wrote, her father “democratized travel, showing the average American how anyone can afford to travel widely and better understand the world.”

As the industry grew and changed, Frommer endured and adapted, speaking with the poise of a litigator and the enthusiasm of a novice, but also with the skepticism of someone who has seen a lot. He was in the business of selling travel, but Frommer saw time abroad as an opportunity to learn, be humble, and become a better global neighbor. He had little patience for people and companies that treated travel as a trap for wealth.

This manifested itself in his budget travel columns (which ran in the LA Times from 1998 to 2007) and in his broadcast and in-person appearances at conferences and travel shows. By the time I met him in the mid-1990s, his signature title had increased to “$50 a day.” (Frommer abandoned that format after it hit $95 in 2007.)

In one of our first conversations, Frommer told me that Pauline had just gotten married. When planning the honeymoon, the proud father said, he had booked a room in the rural highlands of Bali, for $12 a night, with a shared bathroom down the hall.

Arthur and Pauline prepare for “The Travel Show,” their weekly call-in radio show, in 2012.

(Seth Wenig/Associated Press)

Over 25 years, we spoke many times, about traveler's checks, the role of travel agents, the rise of the cruise industry, the ethics of travel boycotts, the scourge of hidden fees, the excitement of finding a new place. I was always impressed by his sense of mission.

He was not the only American guidebook publisher. He wasn't even the only one who focused on the budget. But his voice was clipped and was not always cheerful. In 1988, Frommer warned that “most vacation trips undertaken by Americans were trivial and dull, lacking in meaningful content, uncommercial, and unworthy of our best instincts and ideals.” In an attempt to change that, he published “Arthur Frommer's New World of Travel,” highlighting “life-changing alternative vacations,” including educational programs, volunteer work, and household exchanges—ideas he continued to advocate for decades. .

In 2009, when my LA Times colleague Susan Spano asked Frommer if he was still a budget traveler, he had a typically blunt response ready.

“I've always felt that the less you spend, the more you enjoy,” he said. “The moment you stay in a first-class hotel, you are isolated from life, in a world dedicated to comforts. High-end hotels offer the imaginary experience of living like an aristocrat. But when you go to sleep you no longer know if you are in a one-star or five-star hotel. The large rooms and amenities are absolute nonsense. Go to a guest house. “It's a lot more fun.”

In 2013, Frommer was over 80 years old. Instead of retiring, he bought back the rights to his guidebook series, which endures, covering destinations around the world with pocket guides and e-books. “Fifty-seven years later, I'm getting back to what I originally did,” Frommer said. “I'm probably the oldest rookie editor in the history of the world.”

The grand old man of guidebooks may be gone, but many of us will long follow his example.