We stocked up on supplies, considered building bunkers, and generally prepared for the first technological apocalypse on January 1, 2000, as if it were the end of the world. But the original Y2K came and went, and was nothing compared to Y2K24.

That's what many are calling the CrowdStrike service outage that triggered a global technological calamity on an unprecedented scale.

The details, as we know them, are as follows: cybersecurity firm CloudStrike sent a piece of faulty code to Windows host systems around the world, causing those Windows systems and servers to crash and blue screen across the globe. CloudStrike has thousands of customers, many of them in enterprise, corporate, government, travel, healthcare, and more… the list goes on.

Travel was disrupted, healthcare providers were unable to care for patients, banks were unavailable, stock markets closed, and shipping ground to a halt. Basically, everything went to hell for most of July 19, a day that will go down in history as the worst IT outage in history and our Y2K24.

I didn't invent that term.

A little bit of me on @CNN this morning talking about the #CloudStrike service outage pic.twitter.com/0tckiXxxujJuly 19, 2024

I spent most of Friday on TV explaining the blackout and answering questions. Most of it revolved around how this could have happened, but the TV hosts were equally concerned with how we could prevent this from happening again.

The slow realization that is coming is that the interconnected world we thought we lived in 24 years ago is now real. We thought our globalized system, with everything running on computers that had never been programmed to handle the change of the new millennium, would doom us, but it turned out we were missing a key ingredient: the cloud.

In 1999, cloud computing did not exist and vast services were delivered to millions of people over the Internet, often updated without knowledge, preparation or consent.

Most enterprise-level cloud services (sometimes known as software as a service, or SaaS) get consent from customers and try to prepare them. But when it comes to staying ahead of ever-changing threat factors, that can be difficult. Zero-day attacks mean you need to deliver that update to customers now.

CloudStrike hasn't revealed exactly what happened here or whether this possibly buggy code was security-related or just a feature update. But there's no doubt that this is the wake-up call we needed.

In retrospect, our preparation for Y2K seemed almost absurd because virtually nothing happened. But here we are, 24 hours after the biggest technological collapse in living memory, and some systems are still struggling to recover.

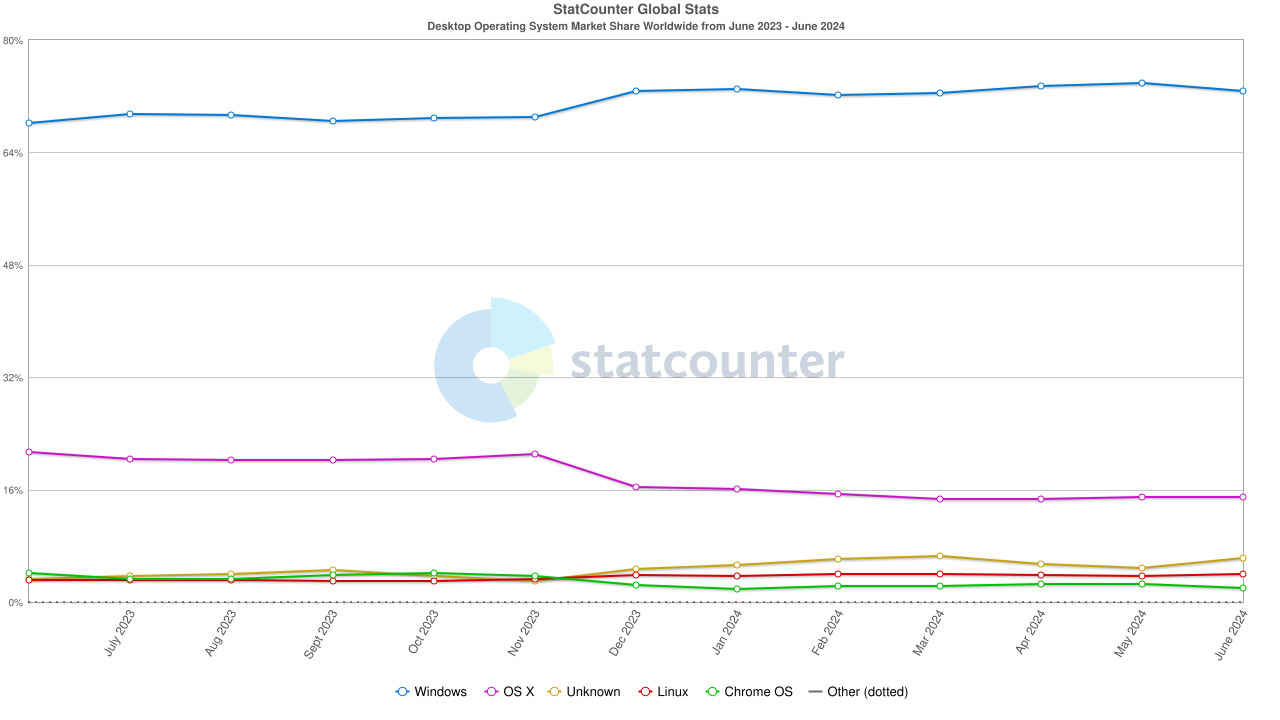

The roots of the global meltdown are easy to trace. CloudStrike serves Windows host systems. Windows is still, by a wide margin, the most popular desktop OS (Statcounter puts it at 72%). It's like a single point of global failure. Windows had over 95% of the market share in 1998. It's clear that the missing component was a dominant cloud service with open-border code delivery to all those Windows systems (not enough companies with sandboxes for incoming code is another problem).

If we don’t take mitigating steps now, such as diversifying cloud-based providers beyond one dominant service, this will happen again. In a way, we had a warning earlier this year when AT&T went down due to another code bug. What’s worse is that we saw how the side effects can easily spread to other, seemingly separate services.

In the case of CloudStrike, it affects so many industries that every time a major breach occurs, everything and everyone is at risk.

The Y2K effect was always real, it just took 24 years to arrive. I didn't add this when I spoke to the presenters, but maybe I should have: I have no idea how we prepare for the next, inevitable global technological collapse.

You may also like