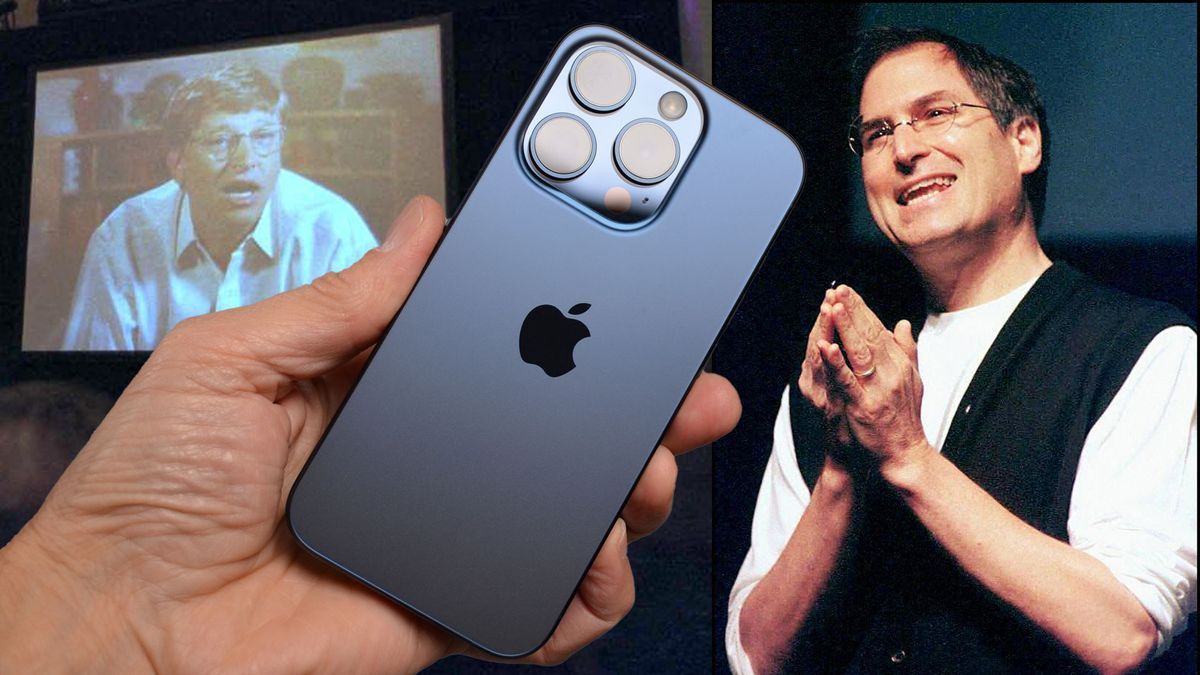

On the eve of another Apple event — one where it unveils a collection of iPhone 16 handsets likely not too dissimilar to last year’s, and the collective tech consumer springs into purchasing action because, well, it’s Apple — it’s worth remembering that, perhaps, none of this would have been possible without an act of charity or calculation on the part of Apple’s once-biggest rival: Microsoft.

I was reminded of the time when Apple, with its good times in the rearview mirror, was relegated to failed Newton handheld consoles, ill-conceived partnerships with Bandai (Pippin gaming console/internet device) and near irrelevance.

In the years after Apple co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs was ousted and returned in early 1997, Apple saw its revenue plummet from a peak of $11 billion to $7 billion. Its losses widened to $125 billion in 1996. There was talk of a merger with Sun Microsystems, something that Apple's then-CEO Gilbert Amelio would not confirm and spokespeople denied. However, it was clear that such talks were further hampering sales of Apple's mostly lackluster Power Macintoshes and Powerbooks.

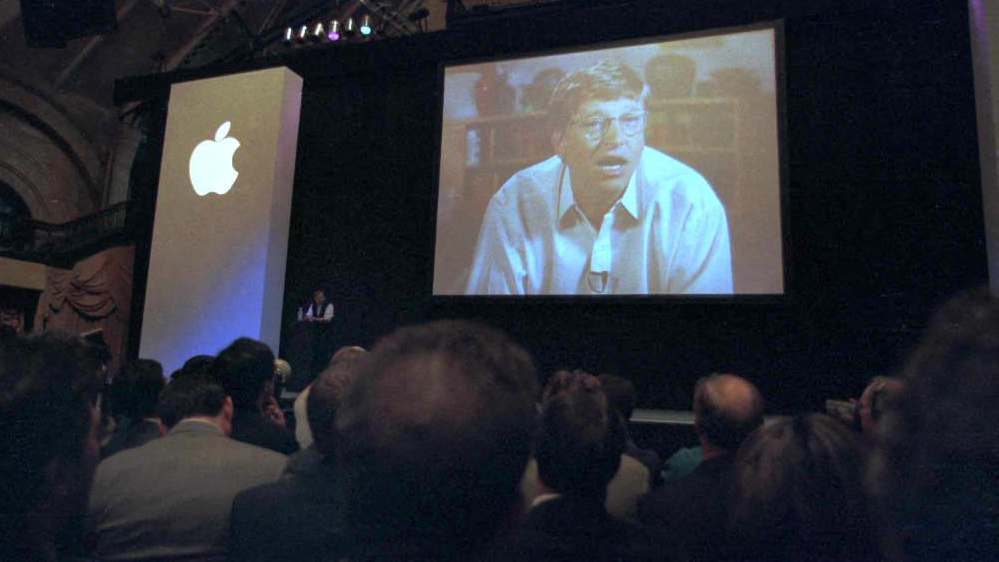

While there is some disagreement about how far Apple was in the red at the time, even Jobs admitted just months after his return that there was work to be done “to get Apple healthy again.” It was during that memorable presentation at Macworld 1997 that Jobs outlined a plan to turn Apple around. Notably, there was not a single new product announcement; it was all about new leadership, new partnerships, and a cash injection from Apple’s biggest rival.

What people remember from that day is that Microsoft agreed to buy $150 million worth of Apple stock (non-voting).

The price of survival

“Yes, but the important part of this that hasn't gotten enough attention is that this included an open license for Microsoft to use a graphical interface for Windows,” veteran Apple analyst and president of Creative Strategies Tim Bajarin told me. Bajarin has been covering Apple almost since its inception.

People like Bajarin, who knew Jobs and the company's sorry state, applauded the rescue (“it was a good, strategic win for both of us”), but not those in attendance at Macworld.

They booed the stock purchase and other elements of the landmark deal (Microsoft's promise to release MS Office for the Mac over the next five years got a more positive response). When Jobs explained that Apple had agreed to make Internet Explorer the default web browser for the Mac, one attendee shouted, “No!”

The reaction was understandable. Apple's business was built on an anti-PC foundation, the opposite of Microsoft's Windows and its more corporate worldview. At one point, antagonism seemed to drive both companies, but those days are gone. As Jobs noted in his presentation, “Relationships that are destructive don't help anybody in this industry as it stands today.”

Of course, Microsoft wasn't acting entirely altruistically. As part of the settlement, Apple agreed to a broad patent settlement and cross-licensing agreement “for all patents, including those filed in the next five years.” This meant that Apple wouldn't pursue Microsoft for using a graphical user interface that was too similar to Mac OS's on any version of Windows.

Incorporating Internet Explorer into another platform helped Microsoft consolidate its growing leadership in the web browser space. I'm not sure that move helped when it faced an antitrust lawsuit in 2000.

Within a year, the value of Microsoft's investment had nearly doubled and only grew from there.

An action that paid off

While the reasons for Apple's fall from grace were manifold (Jobs described it as “executing beautifully on a lot of the wrong things”), there was reason to believe the brand could not only be strong, but a potential powerhouse. During his presentation, Jobs described the brand's incredible recognition and enviable position in the education and creative content market.

In 1997, 64% of all websites, according to Jobs, were designed on a Mac, and 60% of all computers used in education were Macs. The numbers are even more astonishing because, according to Apple's own estimates, the company had some 20 million customers. Today, the company has more than 2 billion.

What Apple lacked for more than a decade, however, was its founder and visionary. Jobs came with ideas (and the remnants of the NeXT platform). Bajarin believes the cash injection gave Apple time to develop the iconic iMac, which was released in August 1998.

Of course, it gave us much more than that. One could argue that without Microsoft's $150 million lifeline, Apple would not have survived. It's possible then that there would have been no

- Without iPod

- Without iPhone

- Without iPad

- Without Apple Watch

- You get the idea.

I can't deny that we wouldn't have gotten there eventually, but the mobile computing revolution could have been delayed by five years or more.

Think about it, it only took $150 million to save a company that would change our lives and eventually be worth trillions.

So as you marvel at the latest iPhone 16, AirPods Pro, and Apple Watches, raise a glass to Microsoft and, yes, Bill Gates, who was roundly booed when he appeared onscreen at Macworld in 1997. Without them, the Apple of 2024 might not even exist.