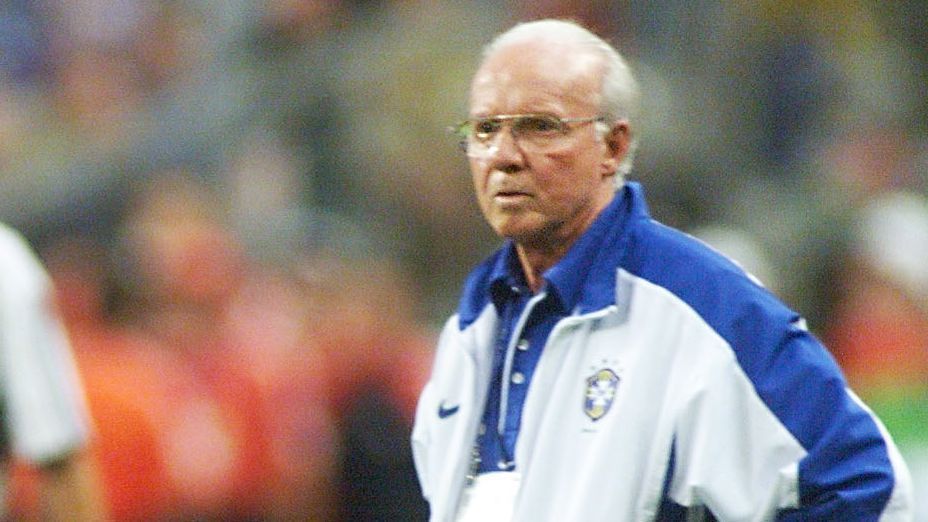

Football lost one of its all-time greats, one of the most influential figures in the game’s history, when Mario Zagallo died on Friday at the age of 92.

If Pelé was the glamorous and magnificent symbol of Brazil’s first three World Cup victories between 1958 and 1970, then Zagallo, as player and coach, was the hard work behind the scenes, who balanced the team and ensured that it made sense. collective. And he can add a fourth World Cup victory: he was an assistant coach when they won again in 1994.

He was on military duty at Rio’s Maracana stadium on the fateful day in 1950 when Brazil lost the World Cup at home to Uruguay, already burning with ambition but barely daring to dream that eight years later he could be part of the team that would win the title. World Cup. trophy. He required a lot of dedication…and a lot of intelligence. He realized that he would never be good enough to break into the national team as a number 10, so he moved on to play on the left wing, where the competition was not as fierce. He wasn’t the most naturally talented left-back in Brazil, but he had something none of the others could offer: the ability to work in midfield.

The first person to win the World Cup as a coach and as a player. 🏆🏆🏆🏆

TO #FIFA World Cup Legend in every sense.

Rest in peace, Mário Zagallo. 💛💚 pic.twitter.com/AWmOvxQKSa

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) January 6, 2024

This was vital. Brazil pioneered the back four system, removing an extra player to the heart of the defense to provide cover. With four forwards (two wingers and a pair of strikers), this left them light in midfield. Years ahead of his time, Zagallo solved this problem.

When Brazil had the ball, he was an attacker. But without possession, he would return to midfield, like a hyperactive “little ant” (his nickname for him). He was two players in one, a winger and a midfielder. This soon became normal, but it was revolutionary when Zagallo did it, and it was critical to the team, perhaps even more so in 1962 than it had been four years earlier.

After winning in Sweden in 1958, Brazil took essentially the same team to Chile in 1962. It was an old team and Pelé was injured in the second match and did not participate in the tournament again. Without Zagallo’s industry on the entire left flank they probably wouldn’t have won that competition. And eight years later, in Mexico, Zagallo was even more important to the cause.

His contribution to the famous 1970 triumph has been constantly ignored. People have looked at the wonderful team and come to the conclusion that the players did everything themselves. This is a serious mistake. Zagallo quickly took over as coach of the team and applied the same principles from his playing career to the task of winning the World Cup.

“I totally changed teams,” he told me when we delved into the subject in 2006. “I didn’t accept the idea of the 4-2-4.” [which Brazil were still playing]. “We wouldn’t have been able to win the World Cup with that system. We had to keep going.”

Not trusting his centre-backs, he moved Wilson da Silva Piazza to the heart of the defence, opening up space for the young, dynamic and elegant Clodoaldo as a central midfielder. And Rivelino came in, improvising on the left wing of the midfield, in an adaptation of the double role of winger and midfielder that Zagallo himself had played so successfully.

The main idea, he stressed, was to prevent the team from being so stretched and so easy to play.

“So,” he continued, “we played in a block, compact, leaving only Tostao on the field. I am happy to see the team in a 4-5-1. We have placed our team behind the line of the ball.”

This was years ahead of its time. Once again Zagallo had managed to balance the desire to attack with the need to defend. The Brazil of 1970 is often considered the pinnacle of football’s possibilities, and this is due as much to the triumph of Zagallo as it was to that of Pelé, Jairzinho, Carlos Alberto and Rivelino.

– Stream on ESPN+: LaLiga, Bundesliga, more (US)

Success in Mexico in 1970 meant Zagallo reached his early peak as a coach. He never had that tactical advantage again. But even so he stood out for the extraordinary strength of his passion for the game and for the Brazilian team. He coached the team to the 1974 semi-finals and 1998 final, and was Carlos Alberto Parreira’s valuable assistant in the 1994 World Cup triumph, and also in Germany’s great disappointment in 2006.

By then, already 70 years old, it was probably too much to ask. But when the opportunity came, he couldn’t turn it down. In 2006 I spoke at length with Zagallo about his history with Pelé and the efforts he made, in vain, to persuade him to play in the 1974 World Cup. Decades later I was still almost incredulous that anyone would pass up the opportunity to represent the country on such an occasion. .

“The decision to opt out of the national team is not something I would make,” Zagallo said.

I pointed out that he would probably play even then if someone picked him. “I wouldn’t run too much,” he said. “But I would play!”

He was a force of nature and global football is even poorer for having lost Mario Zagallo.