BOSTON — At 6-foot-11, Scot Pollard's size helped him play more than a decade in the NBA, earning him a championship ring with the Boston Celtics in 2008.

Now it could be killing him.

Pollard needs a heart transplant, an already dire situation made even more complicated because few donors can provide him with a pump large and strong enough to supply blood to his extra-large body. He was admitted to intensive care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, on Tuesday, and will wait there until a donor who is large enough to be a match comes along.

“I'm staying here until I have a heart,” he said in a text message to The Associated Press on Wednesday night. “My heart weakened. [Doctors] “I agree this is my best chance to get my heart racing.”

At nearly 7 feet tall and with a playing weight of 260 pounds, Pollard's size rules out most potential donors for a heart to replace the one that, due to a genetic condition that was likely triggered by a virus he contracted in 2021, has been beating 10,000 times more per day. Half of his siblings have the same condition, as does his father, who died at age 54, when Scot was 16.

“That was an immediate wake-up call,” Pollard said in a recent phone interview. “You don't see many old people [7-footers] walking around. “So I've known my whole life, just because I had it burned into my brain when I was 16, that… yeah, being tall is cool, but I'm not going to make it to 80.”

Pollard, a first-round draft pick in 1997 after helping Kansas reach the NCAA Sweet 16 in four consecutive seasons, was a utility big man off the bench for much of an NBA career that spanned over 11 years and five teams. He played 55 seconds in the Cleveland Cavaliers' trip to the NBA Finals in 2007, and won it all the following year with the Celtics despite a season-ending ankle injury in February.

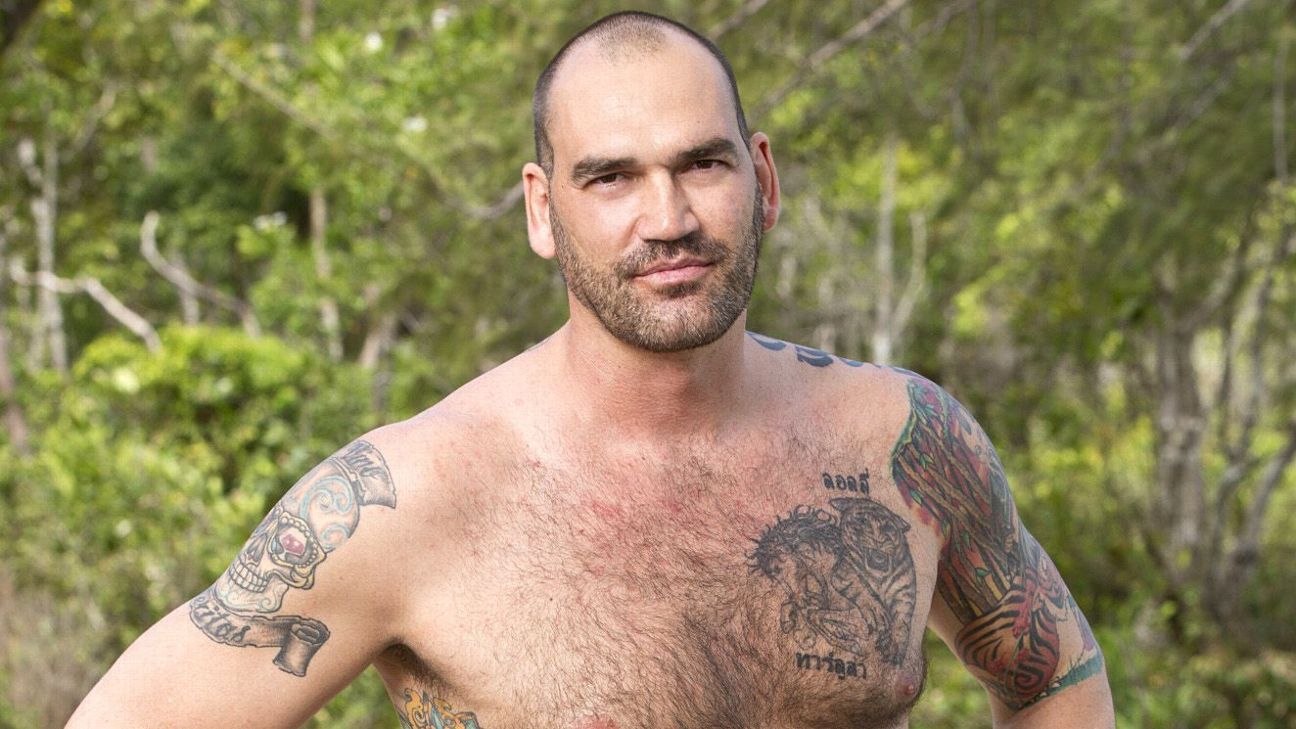

Pollard retired after that season and then ventured into broadcasting and acting. He was a contestant on season 32 of “Survivor”, where he was eliminated on the 27th when there were eight castaways left.

Although Pollard, 48, has been aware of the condition at least since his father died in the 1990s, it wasn't until he became ill three years ago that it began to affect his quality of life.

“It feels like I'm walking uphill all the time,” he said by phone, warning a reporter that he might have to cut the interview short if he got tired.

Pollard tried medications and underwent three ablations — procedures to try to interrupt the signals that cause irregular heartbeats. A pacemaker implanted about a year ago solves only about half the problem.

“Everyone agrees that more ablations are not going to fix this, more medications are not going to fix that,” Pollard said. “We need a transplant.”

Patients who need an organ transplant have to navigate a labyrinthine system that attempts to fairly match donated organs with recipients who need them. The matching process takes the patient's health into account, all with the goal of maximizing benefit from the limited organs available.

“It's out of my hands. It's not even in the doctor's hands,” Pollard said. “It depends on donor networks.”

To maximize his chances, Pollard was recommended to register at as many transplant centers as possible, but he had to be able to get there within four hours; The need to return for postoperative visits also makes treatment away from home difficult.

“I'm increasing my casino odds by going to as many casinos at the same time as possible,” Pollard said.

Pollard checked into Ascension St. Vincent Hospital in his hometown of Carmel, Indiana, and last week underwent testing at the University of Chicago. He traveled this week to Vanderbilt, which performed more heart transplants last year than any other center in the country. Pollard arrived on Sunday; On Tuesday, doctors admitted him to the ICU.

There, Pollard will wait for a new heart, one that's healthy enough to give him a chance and big enough to fit his massive frame. He had been living in Status 4, for those who are in stable condition, but now that he is hospitalized he could be eligible for Status 2, the second highest priority.

“They can't predict it, but they are confident I will receive a heart in weeks, not months,” he texted.

Pollard acknowledged that it's strange to wait for a donor to show up, which is essentially rooting for someone to die.

“The fact is that person will end up saving someone else's life. They will be a hero,” he said. “That's how I see it. I understand what has to happen to get what I need. So it's a really tough mix of emotions.”

Until then, Pollard waits knowing that the same genetics that helped him become a basketball star – so far the defining achievement of his life – threatens to be a deciding factor in his death.

It's something he's known since his father died.

“I've thought about that my whole life,” he said. “I'm from a family of giants. I'm the youngest of six children and I have three brothers who are taller than me. And people always say, 'Oh, man, I wish I was your height.' Yeah? Let's sit together in a plane and see how much you want to be that tall.

“It's not that being tall is a curse. It's not. It's still a blessing. But my whole life I've known there's a good chance I won't age. And that gives you a different perspective on how to do it.” “You live your life and how you treat people and all that kind of stuff.”