One of college sports' most vocal and potentially powerful boosters lashed out at conference commissioners for standing in the way of changes he believes could save the rapidly changing industry, and then the commissioners responded, with one saying the booster's views “reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of the realities of college athletics.”

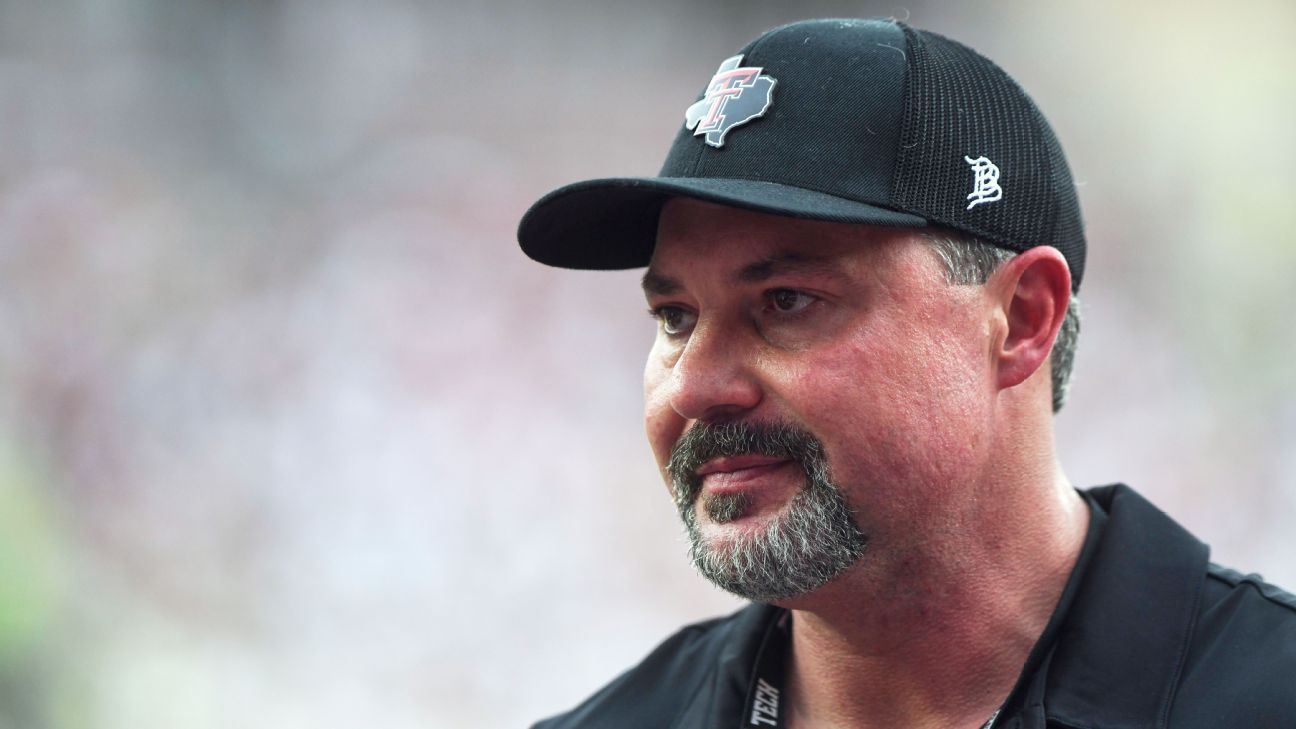

The dispute began with a discussion Thursday by Cody Campbell, Texas Tech's billionaire chief regents, about how the proposal to bundle college television rights could bring additional billions into school coffers, but that progress is slowing because “all the conferences are represented by commissioners who are very, very interested.”

“The commissioners don't really care about what happens at the institutional level,” Campbell said at a roundtable held by the Knight Commission, a watchdog group that released a survey in which the majority of college executives who responded said Division I sports were headed in the wrong direction. “All they care about is what happens to them. And I think that's fundamentally the problem.”

Campbell said he supports elements of the recently introduced SAFE Act, a bill co-sponsored by Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., that includes a call to rewrite a 1960s law that would remove the restriction on college conferences combining to sell their television rights together. Campbell told attendees the measure could be worth $7 billion, and said commissioners had told him “privately” that they know a change to that law would generate more revenue “but I don't want to give up control of my own negotiation over media rights.”

Southeastern Conference commissioner Greg Sankey told The Associated Press that those conversations with Campbell never occurred.

“I have never said, publicly or privately, that bundling media rights would increase revenue, nor do I believe it would,” Sankey said. “His misrepresentation of my position raises serious concerns about the accuracy of his other statements…His comments reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of the realities of college athletics.”

Big 12 Commissioner Brett Yormark also denied making those comments.

“Cody is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts,” Yormark said. “I have never said that sharing media rights will increase revenue. All I have said is that hope is not a strategy. There are unintended consequences to changing the [1961 Sports Broadcasting Act] that Cody and his team need to understand better.

College sports have come under new financial pressure following the recent $2.8 billion House deal that allows schools to directly pay players for the use of their name, image and likeness (NIL) to the tune of up to $20.5 million per university, starting this season.

Media deals form the backbone of most schools' funding. Each of the Power 4 conferences has different, multimillion-dollar deals with different expiration dates spread across multiple networks. Profits from those deals then go to conference offices, each of which has its own formulas for doling them out. The Atlantic Coast Conference, for example, recently changed its formula to base a portion of its payments on the viewership numbers of specific schools.

Meanwhile, the Big Ten has made headlines recently for being in the final stages of its efforts to raise up to $2 billion in private capital, which would create a new entity that would market the league's media rights and other properties.

“The fact that we're bringing private capital into something that I believe is owned by the American public in college sports is crazy,” Campbell said. “We've professionalized this halfway. And so we have a professionalized cost model on the one hand where we pay coaches a lot. Now we're paying players a lot. But we have this amateur media rights marketing effort that makes absolutely no sense to anyone.”

The Big Ten did not respond to a request for comment from the AP. Sankey and Yormark, however, rejected the idea that commissioners are out of touch with what's good for college sports.

“My responsibility lies with the institutions I serve and the student-athletes on our campuses,” Sankey said. “Mr. Campbell's suggestion that commissioners are indifferent at the institutional level is irresponsible and damaging to his own credibility.”

“Our decisions are based on collaboration, accountability and a deep understanding of the institutional impact for student-athletes,” Yormark said. “The SCORE Act is the first step in solving the problems facing college athletics.”

The SCORE Act, which is supported by the NCAA and the Power 4 conferences, proposes limited antitrust protection for the NCAA, primarily from lawsuits involving eligibility issues, and a ban on athletes from becoming employees of their schools, a development that NCAA executive Tim Buckley said would be “the budget buster of the century” for college sports.

Campbell described the SCORE Act as too broad a gift to the NCAA and the conference commissioners he challenged for wanting to run their own fiefdoms instead of looking out for the good of college sports as a whole.

“Protecting his position and protecting his importance and his ego, I couldn't care less about that,” Campbell said. “Because I know that if we don't change something and generate more revenue, a lot of sports will be eliminated, a lot of scholarships will be eliminated, and a lot of kids will lose opportunities.”