Book Review

The grief cure: seeking the end of loss

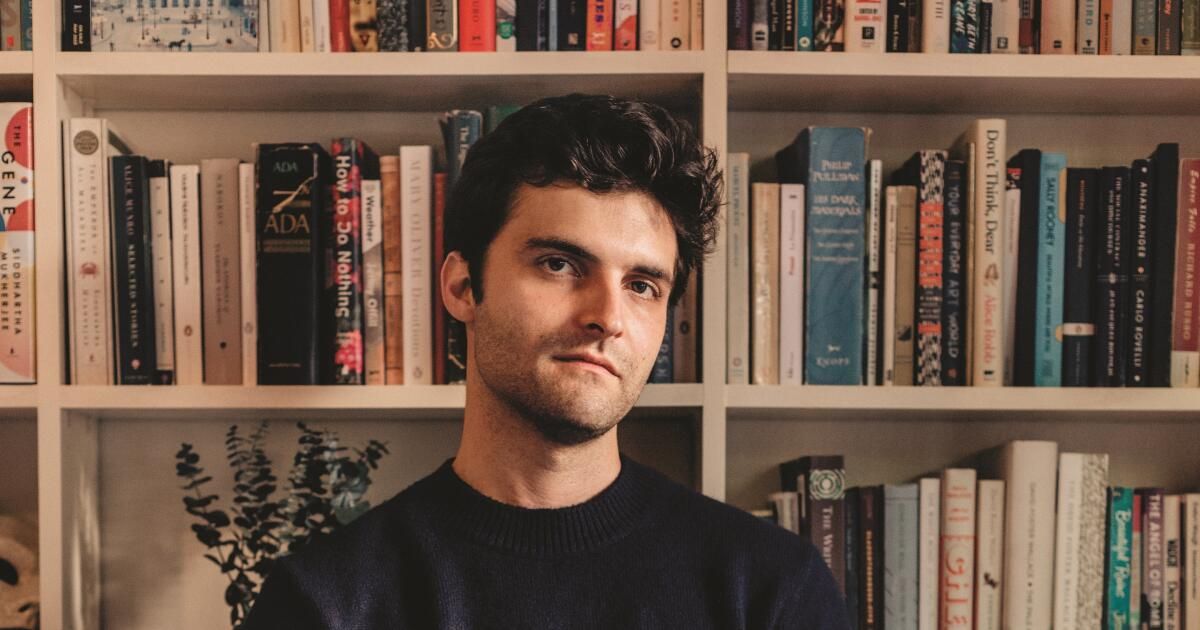

By Cody Delistraty

Harper: $27.99, 208 pages

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When is pain too much pain? Journalist and editor Cody Delistraty examines this question in “The Grief Cure: Looking for the End of Loss,” a hybrid memoir through which he explores the role of Western science, medicine, group therapy, and culture in when facing personal loss. The book revolves around the nearly decade-long grief that Delistraty struggled with following the death of his mother from cancer, emotions so overwhelming that its first chapter begins with the question: “Can a form of grief be a disorder? “

Delistraty is a careful and talented writer; he takes seriously his role as the reader's guide to “better understanding where the future of grief may be headed and the ways in which it is dealt with.” He begins with scientific approaches to the definition of excessive grief, its distinction from depression, and the question of whether it can and should be treated medically. However, Delistraty is more interested in the broader range of options available for dealing with the kind of grief that disrupts long-term well-being, especially how to manage grief as an “emotional as well as bodily experience.” The memoirs offer us a range of experiences through his eyes, with a journalistic inclination. Delistraty tries laughter therapy and therapy that uses literature and art; meditation; psychedelics and pharmacological treatments. He also participates in a breakup boot camp, experiences Day of the Dead rituals firsthand, and reads other grief memoirs. At the same time, he offers analyzes on the possibilities of managing excessive grief rather than verdicts on the effectiveness of these attempts to “cure grief.”

Despite the depth with which Delistraty investigates, some of the conclusions she draws about the role of technology in grief management are surprising in the way they reflect naïve trust. He details the emergence of chatbots like Replika and Project December, and shares his own experience of him “chatting” with an AI version of his late mother. Delistraty links these methods to the 19th and 20th centuries Spiritismwhose followers used photographic technology and telegrams to communicate with the dead and bring a sense of comfort to the grieving.

Delistraty recognizes the clear difference regarding AI and its ability to predict and therefore shape our tastes and decisions in all aspects of our lives. But he posits that AI technology, coupled with a treatment team, could create an “efficient” grieving process that benefits businesses by reducing employee downtime as they deal with personal loss. For Delistraty, given that work expectations around grief are not going to change in the short term (he notes that the average bereavement leave in the United States is three to four days), artificial intelligence technology could be considered “the best path.” to follow”. However, perhaps Delistraty's goal of guiding the reader through all the possibilities of dealing with grief has overridden any judgment about the actual need or effectiveness of AI technology, or the fact that it is ultimately a finite and limited resource (and harmful to the environment). When the credits on Delistraty's chatbot run out, the comforting alternate reality of talking to his mother ceases to exist; “She dies once again,” she writes.

The emphasis on science and technology around what are ultimately ethical considerations makes me wonder if Delistraty had ever seen an episode of the sci-fi series “Black Mirror.” It's not clear that she thinks fully through the implications of some of the issues she discusses. Even an interesting dive into the role of perception and recognition of one's own thought patterns in grief is followed by chapters on using medicine to solve humanity's “deepest problems” and the science that would eventually make it possible. the removal of memories. Despite briefly mentioning the 2004 film “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” which described the detrimental effects of erasing painful memories on personal growth, it is not until a scientist tells him that such interventions do not address the fundamental problems that Underlying the intractable grief that Delistraty admits is that even if it were possible, memory removal may not be the best idea.

Most striking is the loneliness of Delistraty's journey and his apparent faith in the products of the same capitalist systems, like the tech industry, that have standardized that loneliness. The lack of a mourning ritual at the time of death reminds us of one of the many tragedies in the mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic at its outbreak, which led to the dismemberment of the communal rituals of life, particularly weddings and funerals.

As Delistraty points out, funerals themselves have become an industry with rituals, as well as an industry that does not require them. Throughout the memoir, I found myself wondering why the author did not consider issues of community and ritual as fundamental to dealing with his prolonged grief. Although Delistraty addresses these themes, his prose reads more as an intellectual analysis than as an understanding of ritual not simply as an individual interaction between the mourner and the deceased, but as part of how we mourn collectively, as practiced in many cultures and historically in the United States. State.

Although Delistraty seeks wide-ranging “cures,” treatments and therapies, it seems that the real problem underlying prolonged grief lies in the last two sentences of the prologue, when she describes what happened just moments after her mother died: “We stood firm. her body. Then someone knocks on the door: a paramedic with a body bag.”

While Delistraty covers “community” as a broad definition (anything from internet culture to group therapy to grief memoirists), she doesn't focus the lens on loved ones and family as a community. He is constantly perplexed by her mother and her difficult upbringing and religious faith, wishing he had understood her better, but does not seek to understand her life in any meaningful way until it is as a last resort. His father, the widower, is only mentioned at the beginning of the book and then taken up only in the last chapter, “Home.” While spending time with her father and his brother, Delistraty briefly reflects on his father's decision to stay in the same house where his mother became ill and ultimately died, and concludes that he was “beyond” the understanding of him.

It's hard not to think that there is an emotional wall regarding Delistraty and her family, a wall that may be an overlooked but fundamental factor in the nature of their grief. Until that point, everything had revolved around her individual effort to manage grief, but even the chapter on community does not reflect any attempt to share the experience of grief with her own inner circle.

Delistraty's research into the future of how we might cope with grief examines the possibilities ahead. But wouldn't it be a greater loss if the only options available to us were privatized and individualized? There is a fundamental human need to seek comfort not only within ourselves, but also outside ourselves and among ourselves. It is true that, as Delistraty says, pain comes to everyone; His memories make it clear that we must fight harder as a society so as not to have to face it alone.

Raha Rafii is a writer and historian. She writes about law, cultural heritage and digital research technologies.