The lights and sirens of emergency medical services are ubiquitous in the United States. Not only are our screens saturated with them, but it's difficult to go far in any big city without seeing an ambulance rushing by.

The public often assumes that the vehicle is headed toward a life-or-death emergency. But those who have worked in EMS know that, for the vast majority, that is not the case.

What began in the 1960s as a response to increasing carnage on the nation's highways has evolved into a complex subspecialty of American health care. Early research in this field demonstrated that immediate emergency medical care benefits a small subset of patients, that is, those suffering from heart attack and certain types of severe trauma. The enormous marketing success of the 911 system also fueled the expansion of EMS.

Between 1980 and 2010, as the US population increased by 36%, the country's fire departments experienced a 267% explosion in EMS races. The number of life-threatening emergencies obviously didn't grow that quickly, so what happened?

The EMS system became too good at its job, not so much the job of saving lives but the job of showing up within minutes at any time, day or night, for anyone who dials those three numbers. As affordable access to health care continued to erode, 911 was a reliable and readily available substitute.

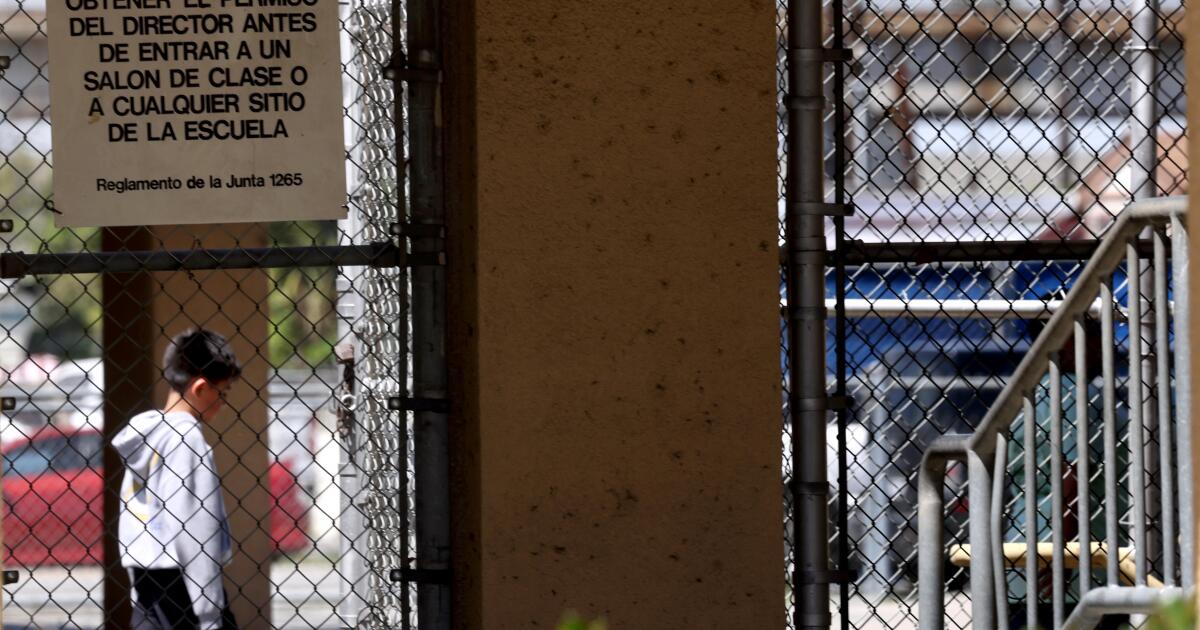

In its fifth decade, the modern EMS system doesn't look much like it did when it was formed. In most cities, it has become commonplace for everything that can go unnoticed in our health care networks: communities with poor access to primary care, homeless populations, and people with mental illness and substance abuse issues. substances, to name a few.

All of these people need and deserve access to health care. The problem is that EMS systems were not designed to handle this volume or breadth of patients. While emergency medical services are less expensive than Byzantine hospital systems, they are by no means cheap.

EMS is a labor- and equipment-intensive industry that struggles to recruit staff, collect insurance reimbursement, and, most recently, transport patients to emergency rooms in a timely manner. As a result, their ability to respond to any rapid increase in demand for care is very limited.

Take the Los Angeles Fire Department, which responded to nearly half a million calls for service in 2022 (a 10.3% increase over 2018) for a ratio of 1 response per 7.8 residents. To accomplish this feat, the department operates approximately 150 ambulances per day at its 106 fire stations. While that sounds like a lot of resources, the truth is that it is only enough to cover 0.004% of the population at any given time. This is just one example of the vulnerability of our overloaded EMS system.

Further exacerbating the difficulties in providing EMS coverage, usage patterns are notoriously uneven; certain neighborhoods rarely use the system, while others rely on it for most of their health care. But it can't simply be eliminated from neighborhoods that don't use it much.

Homelessness is an extreme example of these divergent patterns. They represent only 0.8% of the population, but account for 10.2% of the city's EMS calls, using the service in 14 times the rate of housed residents.

Recognizing that it is difficult to improve something that is not measured, the LAFD has been a leader in EMS research. One example was an evaluation of more than 33,000 calls for abdominal pain over a three-year period to see how many turned out to be life-threatening emergencies. The answer, surprisingly, was simply Seven.

Los Angeles is not alone; The staggering growth in non-emergency calls has affected services across the country. A 2021 study of nearly 6 million 911 calls involving nearly 1,200 U.S. agencies found that while 86% of responses sent crews running with lights and sirens on, less than 7% resulted in a potentially life-saving intervention.

The repercussions of inadequate healthcare are rampant in calls to emergency medical services and emergency departments. Only 8% of Americans age 35 and older receive all recommended preventive services and screenings, and 1 in 8 of people ages 12 to 65 does not have health insurance. Complications from diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, obesity, and alcohol consumption overwhelm the healthcare system in volume and cost. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 90% of US health spending goes toward treatment. chronic conditions.

As EMS has been forced to fill the gaps, it has become clear that it is neither sustainable nor effective in that role. Meanwhile, their ability to respond effectively to life-threatening emergencies has been affected.

Many local leaders are aware of this and are looking for answers. Strategies they have implemented include referring non-emergency calls to nursing hotlines, employing alternative transportation to sober living centers and urgent care clinics, and bringing mental health professionals to patients. Much effort has been spent trying to discourage non-emergency 911 calls with minimal success.

It has become clear that the answer is not so much to discourage the public from calling 911 as to change what happens when the calls come. One obstacle has been accurately identifying conditions that are not life-threatening. EMS systems have generally chosen to make a pronounced mistake by tolerating non-emergency calls to avoid liability. Refining dispatch algorithms and integrating physician and nurse assessment can help alleviate the impulse to simply dispatch an ambulance.

Ultimately, 911 centers will need to be viewed as health care centers and ambulance transportation as if only one spoke to providing them. The ability to triage patients like an emergency room does and dispatch the appropriate response (whether an ambulance, taxi, or mobile lab) can help conserve resources.

Above all, any large-scale solution will require system-wide access to primary care for people who call 911. The ultimate goal, which our modern EMS system has largely lost sight of, is to help people obtain the most appropriate and effective care.

Jon Nevin is a Southern California Fire Department Battalion Chief and a long-time emergency medical services practitioner and researcher.