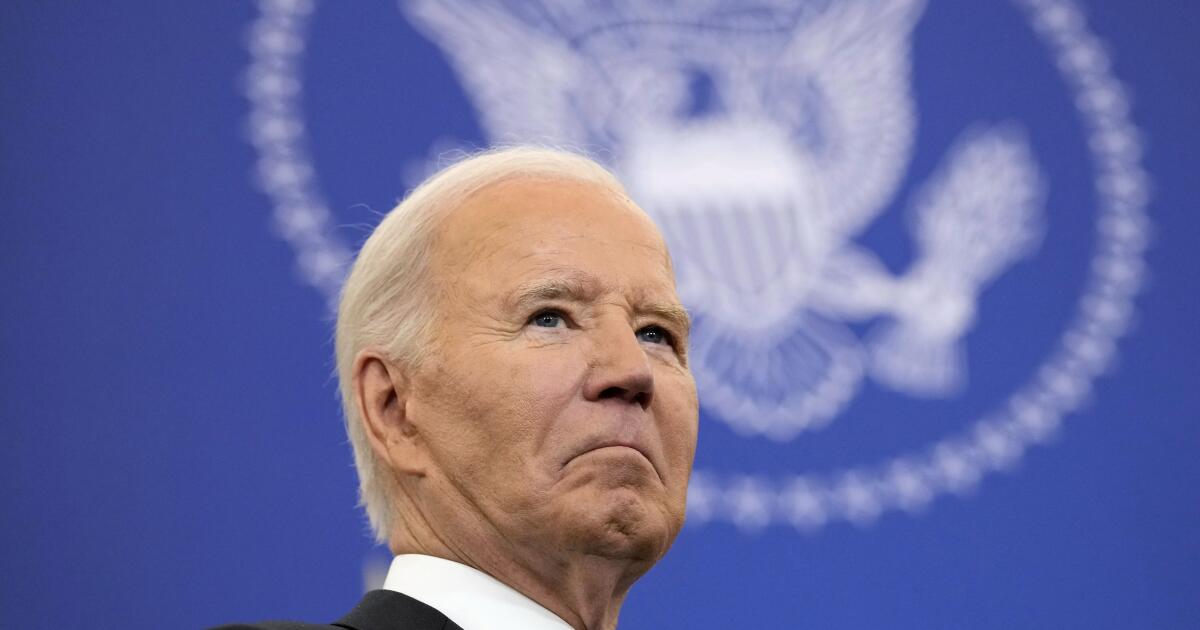

Smart Republicans could have foreseen that a day like this would come — and worked hard to prevent it — in 2010.

That was the year that Kamala Harris, a brilliant, young and charismatic prosecutor from San Francisco, ran her first statewide campaign for California attorney general and eventually won. The race foreshadowed the politics of 2020 and possibly 2024.

Republicans could not have predicted 14 years ago that Harris would become the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee in 2024. But they could be confident that if she prevailed then, the state’s top law enforcement post would not be her last stop.

After all, in California and other states, the position is a stepping stone: AG means not only attorney general, but also a candidate for governor. That's why many Republicans thought it would be easier to stop Harris's rise before it began.

At the start of her presidential campaign, Harris is trailing Republican candidate Donald Trump in most polls, a position that feels familiar to her.

Harris was an underdog when she ran for San Francisco district attorney against a well-known incumbent, Terrance Hallinan, in 2003. He won that race Partly because of her stance to the right of Hallinan, the San Francisco Chronicle endorsed her with the headline: “Harris, for law and order.”

But she could not stray too far from San Francisco's liberal orthodoxy, and she also made a costly promise not to seek the death penalty if elected.

Three months after she took office, a man shot and killed Isaac Espinoza, a young San Francisco police officer, husband and father. True to her word, the new district attorney announced that she would not seek the maximum punishment. The response was swift and brutal.

Senator Dianne Feinstein He spoke at the officer's funeral. And as Harris sat in a pew at the front of the cathedral, he said the police officer's killer should have been charged with a capital crime. The officers filling the cavernous cathedral stood and applauded. Harris did not.

Prosecutors obtained a conviction for second-degree murder and a life sentenceBut Harris’ decision not to seek the death penalty resurfaced in the 2010 campaign, and will likely resurface in 2024.

Harris was again the underdog in 2010, when she ran against Republican Steve Cooley, a three-term Los Angeles County district attorney who had spent most of his tenure in office. Four decades as a prosecutorSome Democratic Party veterans publicly predicted Harris would lose to Cooley, similar to what Democratic pundits have done more recently who questioned Harris’ ability to run a national campaign.

Cooley was a prosecutor who looked like he stepped out of a leading man role, as Trump would say, gray-haired and a bit disheveled, who gave the impression that he had seen more than his share of crime victims' pain. He was known for bringing successful cases against corrupt politicians and convicted murderers alike.

The Tea Party movement helped Republicans take control of the House of Representatives and state legislatures across the country in 2010. They had legitimate hopes of making gains in California, too, and the attorney general’s office was a prime target. A national political action committee spent more than $1 million attacking Harris’s handling of the Espinoza killing, hoping to stop her rise before it began.

“If that's a consequence of defeating her, we're perfectly happy with that,” a PAC spokesperson, who was covering it for the Sacramento Bee, told me a few weeks before the election.

The Republican primary had also foreshadowed what was to come. Cooley faced a challenge from the right in the person of John Eastman, the former dean of Chapman University’s law school who later played a key role in Trump’s failed attempt to overturn the 2020 election.

Among Eastman’s donors was Federalist Society leader Leonard Leo, who would be instrumental in Trump’s nomination of Supreme Court justices who helped end federal abortion rights. That decision is critical for the 2024 election, perhaps even more so given Harris’s likely nomination.

Although Eastman’s primary campaign failed, it did not leave the eventual candidate unscathed. Eastman had raised the possibility that, if elected, Cooley would collect his Los Angeles County pension in addition to his salary as attorney general, for a combined annual salary of about $425,000. During Cooley’s only debate with Harris, which I moderated, the Los Angeles Times’ Jack Leonard asked the Republican if he would actually collect his pension along with his salary. Cooley answered that he had earned the pension and would take it “to supplement the very low, incredibly low, salary that is paid to the state attorney general.”

Harris saw the answer for what it was — a little too honest — and left it at that. “Go ahead, Steve,” she said. “You’ve earned it; there’s no question about it.” The exchange became fodder for a pointed Harris campaign ad.

In the end, the 2010 Republican wave stalled on the eastern slope of the Sierra. Harris won by about 74,000 votes out of 9.6 million cast, the narrowest margin statewide that year.

A decade later, Eastman wrote a column questioning Harris's qualifications for the vice presidency on the grounds that her parents were not naturalized citizens when she was born. marginal theoryYes, but it caught Trump's attention and is already being… resurrected.

In the coming weeks, Harris will face all kinds of attacks. Some may be substantial, but I'm guessing most will border on the ridiculous. Can you imagine? The candidate laughs. And dances!

During Harris’s campaigns for California attorney general and U.S. senator, I saw firsthand what kind of candidate she can be: tough, formidable, disciplined. Republicans should surely wish they had stopped her when they had their best chance.

Dan Morain is a former Times reporter and the author of “Kamala's Way: An American Life.”