New research from cybersecurity company Mandiant provides surprising statistics on vulnerability exploitation by attackers, based on the analysis of 138 different exploited vulnerabilities that were revealed in 2023.

The findings, published on the Google Cloud blog, reveal that providers are increasingly being targeted by attackers, who are continually reducing the average time to exploit zero-day and N-day vulnerabilities. However, not all vulnerabilities have the same value for attackers, since its importance depends on the attacker's specific objectives.

Uptime is decreasing significantly

Exploit time is a metric that defines the average time it takes to exploit a vulnerability before or after a patch is released. Mandiant research indicates:

- From 2018 to 2019, the TTE lasted 63 days.

- From 2020 to 2021, it fell to 44 days.

- From 2021 to 2022, the TTE was reduced further, to 32 days.

- In 2023, the TTE remained at only 5 days.

SEE: How to create an effective cybersecurity awareness program (TechRepublic Premium)

Day Zero vs. Day N

As TTE continues to reduce, attackers are increasingly exploiting zero-day and N-day vulnerabilities.

A zero-day vulnerability is an exploit that has not been patched and is often unknown to the vendor or the public. An N-day vulnerability is a known flaw that is exploited for the first time after patches are available. Therefore, it is possible for an attacker to exploit an N-day vulnerability as long as it has not been patched on the target system.

Mandiant exposes a 30:70 ratio of N days to zero days in 2023, while the ratio was 38:62 in 2021-2022. Mandiant researchers Casey Charrier and Robert Weiner report that this change is likely due to the increased use and detection of zero-day exploits, rather than a drop in the use of N-day exploits. It is also possible that actors threats have had more successful attempts to exploit zero days in 2023.

“While we have previously seen and continue to expect increasing use of zero-days over time, in 2023 there was an even greater discrepancy between the exploitation of zero-days and the exploitation of n-days, as the zero-day exploitation surpassed n-day exploitation more strongly than we did. we have previously observed,” the researchers wrote.

N-day vulnerabilities are primarily exploited during the first month after patching

Mandiant reports that they observed 23 N-day vulnerabilities being exploited in the first month after releasing their fixes, however, 5% of them were exploited in one day, 29% in one week, and more than half (56% ) in a month. In total, 39 N-day vulnerabilities were exploited during the first six months after the release of their fixes.

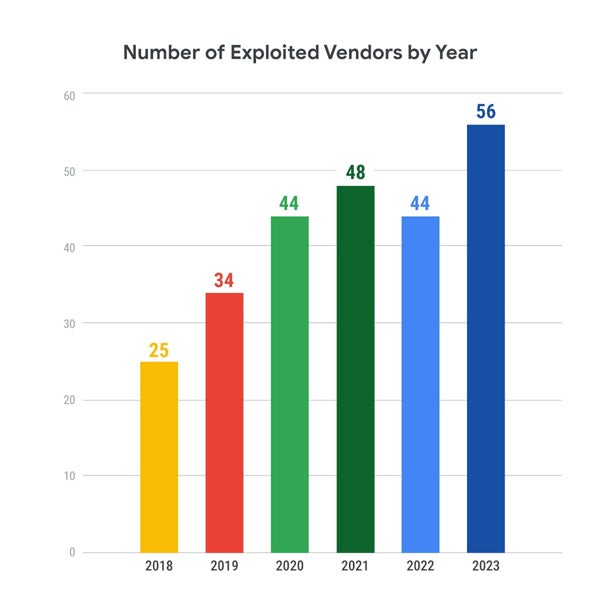

More suppliers targeted

Attackers appear to be adding more vendors to their target list, which increased from 25 vendors in 2018 to 56 in 2023. This makes it more challenging for defenders, who are trying to protect a larger attack surface each year.

Case studies describe the severity of exploitations

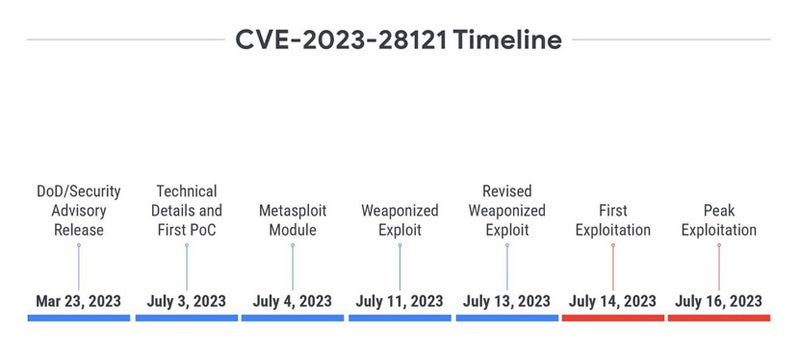

Mandiant exposes the case of the CVE-2023-28121 vulnerability in the WooCommerce Payments plugin for WordPress.

Released on March 23, 2023, it received no proof of concept or technical details until more than three months later, when a post showed how to exploit it to create an admin user without prior authentication. A day later, a Metasploit module was released.

A few days later, another weaponized exploit was released. The first exploit began one day after the revised weaponized exploit was released, with exploitation peaking two days later, reaching 1.3 million attacks in a single day. This case highlights “increased motivation for a threat actor to exploit this vulnerability because a functional, reliable, and large-scale exploit is made available to the public,” as Charrier and Weiner stated.

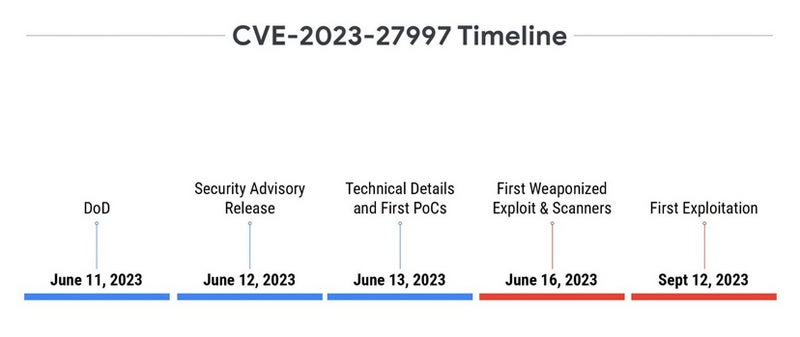

The case of CVE-2023-27997 is different. The vulnerability, known as XORtigate, affects the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/virtual private network (VPN) component of Fortinet FortiOS. The vulnerability was revealed on June 11, 2023, and immediately appeared in the media, even before Fortinet published its official security advisory a day later.

On the second day after disclosure, two blog posts containing PoC were published and an unarmed exploit was posted to GitHub before being removed. Although the interest seemed evident, the first exploitation came only four months after the disclosure.

One of the most likely explanations for the variation in observed timelines is the difference in reliability and ease of exploitation between the two vulnerabilities. The one affecting the WooCommerce Payments plugin for WordPress is easy to exploit as it simply needs a specific HTTP header. The second is a heap-based buffer overflow vulnerability, which is much more difficult to exploit. This is especially true on systems that have various standard and non-standard protections, making it difficult to trigger a reliable exploit.

A key consideration, as Mandiant explains, also lies in the intended use of the exploit.

“Directing more energy toward developing the more difficult, but 'more valuable' vulnerability would make sense if it better aligns with your goals, while the easier to exploit and 'less valuable' vulnerability may present more value to more opportunistic adversaries.” . ”the researchers wrote.

Implementing patches is not an easy task

More than ever, it is mandatory to deploy patches as soon as possible to fix vulnerabilities, depending on the risk associated with the vulnerability.

Fred Raynal, CEO of Quarkslab, a French offensive and defensive security company, told TechRepublic that “patching 2 or 3 systems is one thing. Patching 10,000 systems is not the same. It takes organization, people, time management. So even if the patch is available, it usually takes a few days to release it.”

Raynal added that some systems take longer to patch. He took the example of the mobile phone vulnerability patch: “When there is a fix in the Android source code, Google has to apply it. So SoC manufacturers (Qualcomm, Mediatek, etc.) have to test it and apply it to their own version. Then phone manufacturers (e.g. Samsung, Xiaomi) have to adapt it to their own version. Then, operators sometimes customize the firmware before compiling it, so they can't always use the latest versions from source. So here, the propagation of a patch is… long. It is not uncommon to find 6-month-old vulnerabilities in current phones.”

Raynal also insists that availability is a key factor when deploying patches: “Some systems can afford to fail! Consider an oil rig or any energy manufacturer: patching is fine, but what if the patch causes a failure? No more energy. So what's the worst? A critical system without patches or a city without power? An unpatched critical system is a potential threat. A city without power, these are real issues.”

Finally, according to Raynal, some systems do not have any patches: “In some areas, patches are prohibited. For example, many companies that make health devices prevent their users from applying patches. If they do, the warranty is void.”