Book Review

The Riverside Boys: A Deaf Football Team and a Quest for Glory

By Thomas Fuller

Doubleday: 256 pages, $28

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

For starters, it’s an inspiring story: The football team at the California School for the Deaf in Riverside had endured 51 losing seasons, and in nearly a dozen of them, they lost every game. But then came 2021, when everything changed and journalist Thomas Fuller heard their story. “I was drawn to it like metal to a magnet,” he writes in his new book, “The Boys of Riverside.” Fuller follows two winning seasons for the Cubs, told in nonfiction narrative at its finest, packed with drama, detail and action.

In late fall 2021, the school wrote to Fuller, a Bay Area-based reporter for the New York Times, to tout the team’s unexpected winning season: The Cubs were in the playoffs for the first time in history. The email was sent in hopes of garnering donations for new bleachers, but that wasn’t what interested Fuller. The team’s broader story was irresistible.

He took a leave of absence from the newspaper, moved to Riverside and joined the Cubs.

Radical! Risky! But it's really the only way to tell the whole story.

“The Boys of Riverside” is roughly divided into two parts: the 2021 season, which Fuller joined late that fall, and the 2022 season, which he watched every minute of and recounted with enthusiasm.

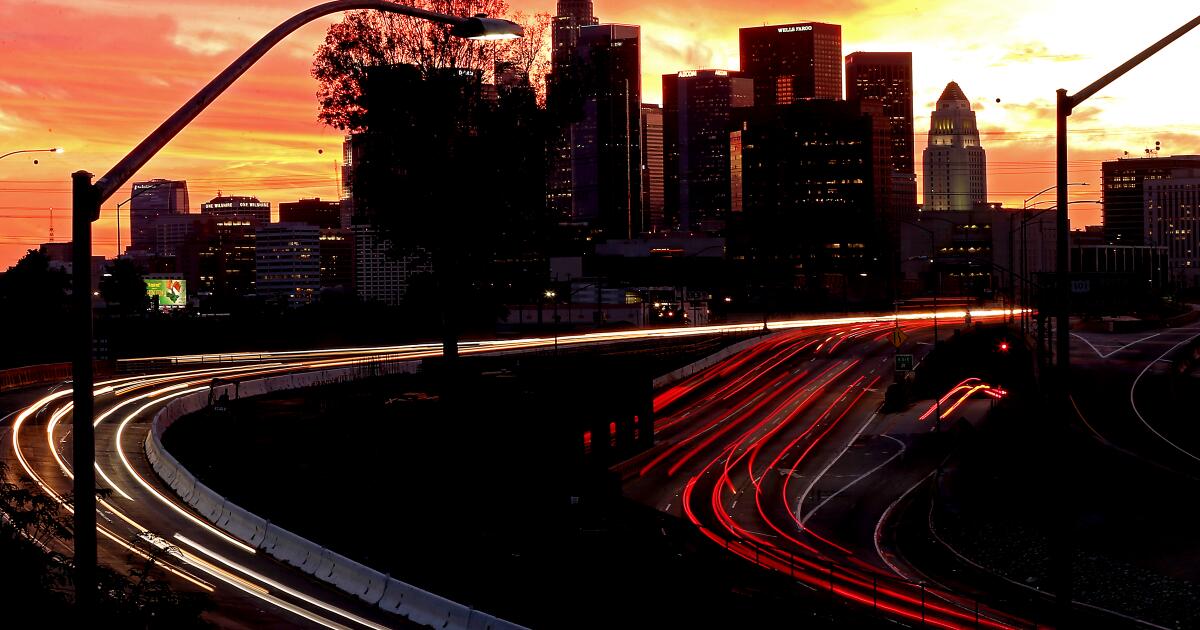

Players from the California School for the Deaf communicate using sign language during a 2022 game in Riverside.

(Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times)

Perhaps because Fuller came so late to the 2021 season, the first half of the book is less vivid than the second. We get to know some of the players, but only superficially. The book is packed with background and history, necessary information that could have been spread out in smaller chunks throughout the book.

But bear with us. The story opens as the 2022 season begins and never loses its rhythm.

Nearly half of Riverside High’s 51 students were on the football team. They played in an eight-man division rather than the more traditional 11-man division, but “smaller … doesn’t mean less athletic,” Fuller writes.. And these guys are tough, to be sure: One player breaks his leg during a game, then buys a brace on Amazon so he can rejoin the team. Another breaks his ankle but finishes the game. A third does his best to play despite being sick with atypical pneumonia. “He looked like a ghost, his sunken eyes ringed with black circles and his bony face more drawn than usual,” Fuller writes. “He wasn’t as jovial as before, but he had greeted his family that morning with a mantra: ‘I’m playing! I’m playing! I’m playing!’”

What made the 2021 team so special? Fuller attempts to answer the question, but it’s not quantifiable. “Success in sports almost always involves more than raw athletic talent,” he writes. “There’s another crucial intangible: the mechanics and mysteries of successful teamwork.”

The team’s cohesion is due in part to the players’ deafness. Not being able to hear doesn’t put them at a disadvantage; in many ways, Fuller comes to understand, being deaf is an advantage on the field. The players pay intense attention to their coach and each other, and they rely on visual rather than verbal cues (they’re never penalized for being offside, for example, because they don’t move until the ball does). They’re not distracted by cheering crowds, trash talk or announcers. And when they do huddle or confer, they can conceal their intentions from opposing teams, who presumably don’t know American Sign Language.

Riverside's players come from many countries and cultures (Mexican, Romanian, Ethiopian and Native, to name a few); they have different economic backgrounds (one lives in a car parked in a Target parking lot); and they have different experiences. Several of the players began their soccer careers at mainstream schools, where they were relegated to lesser positions on the team because communication was a challenge. But at Riverside, they flourished.

“In writing the book, I came to see the Cubs as the embodiment of the American dream in flesh and blood,” Fuller writes.

The action takes place in the last third of the book, as the Cubs make the playoffs again, and the final chapters are game stories, told almost minute by minute. Fuller keeps the chapters short and dramatic, the pace fast and the sentences concise. He doesn't hint at the outcome, but lets the story unfold.

What's the best way to end this book? If the Cubs lose, will the book be meaningless? If they win, will it be a feel-good cliché?

Fuller recovers from his slow start like a running back recovers from a tackle attempt and runs toward the end zone with gusto.

Laurie Hertzel teaches in the low-residency MFA program in narrative nonfiction at the University of Georgia.