Book review

The supreme law of the land: How the unbridled power of sheriffs threatens democracy

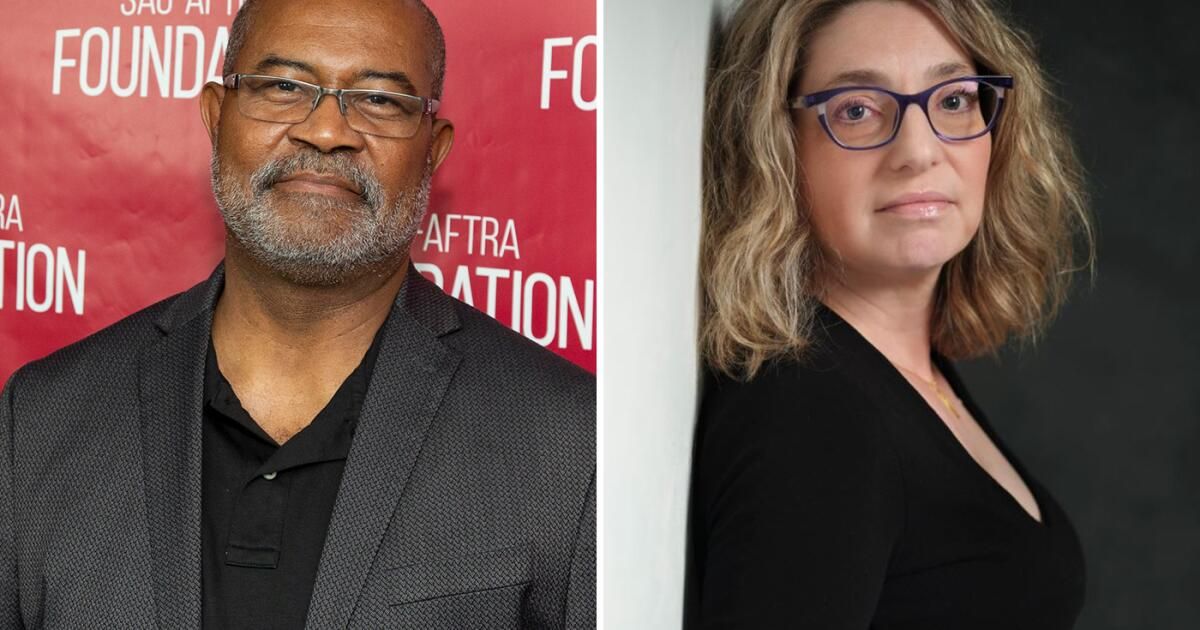

By Jessica Pishko

Dutton: 480 pages, $32

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Book review

Zion's Gangs: A Black Cop's Crusade in Mormon Country

By Ron Stallworth

Legacy: 288 pages, $30

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A stock character in American crime stories is the maverick cop, the hero who rebels against the system and bends the rules to catch the bad guys. Intrinsic to the macho stereotype is that his shield (or, rarely, hers) is backed by physical violence, or that his ever-present gun is his ultimate expression of authority.

Two new books by Ron Stallworth and Jessica Pishko It looks at American law enforcement from different perspectives, both of which highlight the dangers when this fictional trope becomes reality.

Stallworth, the retired police detective and author of “Black Ku Klux Klan member” He takes readers on a journey as he recounts his years with the Salt Lake Area Gang Project and his mission to end gang activity among Mormon youth.

Pishko, an investigative journalist, turns readers into witnesses in interviews with those who declare themselves “constitutional sheriffs.” They claim that their legal authority is based on a certain reading of the Constitution, making them arbiters of the laws they administer, or do not administer — within their jurisdictions.

As a lawyer, Pishko performs a tour de force of investigative journalism and astute legal analysis of how these sheriffs turn their counties into fiefdoms. In the United States, 3,000 sheriffs in 46 states are the primary police force for 56 million Americans. Sheriffs make 20% of all arrests in the country and account for 30% of the annual officer-involved murders. They are also overwhelmingly white and male: Black sheriffs make up 4%; only 2% are women.

In this case, race matters. In whitewashed histories of the American West, maverick sheriffs stood their ground to protect white settlers, and in reality they have been tools of white supremacists. Sheriffs sought out and captured people who had escaped slavery; enforced the Black Codes after Reconstruction; and aided the forced removal and murder of Native Americans on tribal lands. Today, sheriffs are the administrators of county jails and, as Pishko documents, have control over many people targeted by racist law enforcement.

Prisons are the scene of gross violations of basic civil rights (detention without appearance, confinement of the mentally ill, lack of segregation between violent criminals and those arrested for traffic violations), with horrific results. An arrest for shoplifting led to The death of the suspect in a Los Angeles County jail in 2022; Fresno County In 2018, 11 prisoners died and 13 others required hospitalization after being beaten.

Sheriffs have resisted efforts to reform county jails. As sole administrators, sheriffs directly benefit from the daily payments they receive for each inmate. Full jails mean maximum revenue.

If county voters continue to support them, there are few avenues to discipline sheriffs for corruption or for failing to enforce laws they personally disagree with. rightist groups and white nationalists find compassion and protection from sheriffs who hold similar beliefs. Pishko points to the reliance on sheriffs to enforce the law: “We have no other mechanism to hold white supremacists accountable other than an institution that is itself a product of white supremacy.”

In tune with growth fascist movementConstitutional sheriffs claim ultimate authority, even surpassing federal law enforcement.

Pishko cites an example from Pinal County, Arizona, where Sheriff Mark Lamb made the same point at a rally. “We are not politicians,” he said, even though he holds elected office and ran for Senate this year. “I am the sheriff of your county. My job is to protect people from bad guys and from the excesses of government.”

In several counties, constitutional sheriffs have refused to enforce state or local mask mandates or firearms regulations. They claim the right to verify immigration status and have appointed themselves Guardians of the Voteciting the Big Lie and other conspiracy theories about “unfair” democratic elections.

The conservative Claremont Institute in California offers sheriff scholarshipswhere sheriffs who claim extreme powers have a legal framework and a philosophical basis for legitimation. Claremont’s radical promotion of his “nihilistic desire to destroy modernity,” as Pishko puts it, has made him “an indispensable part of the American right’s evolution toward authoritarianism.”

Strict gender hierarchies, racial hierarchies, and an aggressive heteronormativity that sees “deviance” everywhere underlie constitutional sheriffs’ interactions with the public. They embody a toxic hypermasculinity that relies on violence, a willfully ignorant interpretation of the Second Amendment, and a rejection of traditional authorities, such as scientists.

Violence and similar themes of hypermasculinity are explored in Stallworth’s fascinating account of his work as the Crips and Bloods established strongholds in Salt Lake City. By teaching police officers to classify children not based on their race but on the color symbols that identified them as gang members, he attempted to deflect the racial profiling that informs many police officers’ interactions with black and Latino communities.

Stallworth writes that he also took gangster rap seriously as a source for understanding “an intellectual upheaval in the body politic, especially in the police establishment.” Many lyrics denounced police brutality. Others, he argued, rejected the “white social castration” of black men by the mainstream culture and instead “exaggerated their masculinity through the psychological subjugation of women.”

Stallworth's own accounts of his police work are also troubling. In his account, he takes the bait when provoked and lashes out, even escalating conflicts, as when he challenges a gang member to a fight while his armed white partner looks on or when he responds to racial epithets from white supremacists with his own misogynistic statements of sexual domination over their mothers. In 2019, he shook hands with Director Boots Riley, who had He criticized a film based on Stallworth's lifeHe then incapacitated him while grabbing a pressure point on Riley's neck.

“The Gangs of Zion” alternates between a well-researched and thoughtful analysis of gang culture and Stallworth’s behavior in walking the thin blue line when he ignores the civil rights of suspects or claims that rules made by those without experience as “street cops” don’t apply to him.

Stallworth explains the role that white supremacy plays in the policing of bad cops in black communities. Because his gang-related work was in Utah, the Mormon church looms large: despite the arrest of white gang members carrying the Book of Mormon in their pockets, the church maintains that only ethnic minorities are to blame for the gang problem in the area. The church’s official responses are based on creating its own facts to fit that narrative.

But Stallworth himself does not question another disturbing narrative: that drug dealers are “young punks” who need to be punished. He acknowledges the racism that led many to reject hip-hop; why does he not examine whether the “war on drugs” is also a threat? fueled by racism? It has served for decades as a pretext for mass incarceration of Black and Brown people.

Rather than dealing with that reality, “The Gangs of Zion” embraces the idea of “good” cops enforcing the law with questionable methods. Stallworth embodies that same reckless hypermasculinity seen in the constitutional sheriffs profiled by Pishko; both cite disturbing claims to justify using any means necessary to achieve their goals.

That’s where the key difference lies: Whereas Stallworth was a cop dedicated to enforcing the law (however problematic it may be), these sheriffs’ goal is to disregard the law and pose a threat to society. They see their mission as upholding white supremacy and a rising fascist movement.

Lorraine Berry is a writer and critic living in Oregon.