Book review

Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian's Journey Home

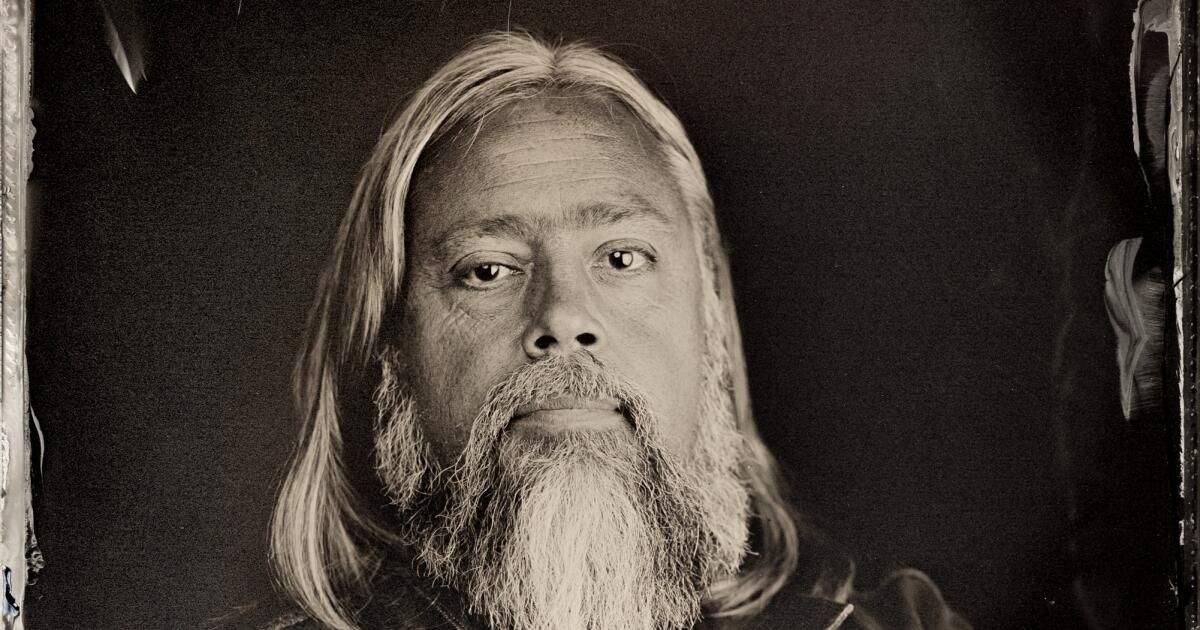

By Chris La Tray

Cottonwood: 320 pages, $28

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

What does it mean to “belong”? And how do we know when we feel it?

In “Becoming Little Shell,” Chris La Tray, a storyteller and member of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, sets out to explore the meanings of belonging in a country where many of the things that once created a sense of belonging—ties to the land, knowing one’s heritage—have been replaced by “story.”

Tray acknowledges that not all Americans feel this loss as deeply. “For many people, much of this seems like ancient history, the ‘good old days,’ as we called them as children when we chased each other around with toy guns and rifles,” he writes. “The reality is that it is a living, ongoing history that deeply affects the lives of many people every day.”

Even within his own family, La Tray found himself isolated from his ancestry. His father was mixed-race and Chippewa, his mother white, but his father refused to acknowledge his heritage. It wasn’t until 1996, when young La Tray was 29, at his grandfather’s funeral, with the pews packed with Native Americans, that he realized he didn’t know what tied him to this community of mourners.

Tray sums up the years between his grandfather's death and a particular weekend in October 2013. “Overcoming a Western Legacy,” a talk given by the historian Nicholas Vrooman At the Montana Book Festival, La Tray was galvanized. Learning about Little Shell, a landless tribal nation in Montana that includes a mixed-race European-American people, revealed missing parts of his identity and moved him to action.

La Tray's memoir is not just about her ties to a people; it is also an expansive and moving memoir of the land and the indigenous people who lived in Montana for 3,000 to 5,000 years before the westward expansion of European settlers.

Seventeenth-century French explorers and indigenous peoples in what is now Canada and the United States formed trading cooperatives that were often consolidated through marriage. The Métis, their descendants, and the dispossessed Pembina Chippewa diaspora inhabited lands stretching from Coeur d'Alene to Fargo and from Saskatoon to Sioux Falls.

La Tray’s journey to discover her own identity is paralleled by an effort by the Little Shell Nation in recent decades to gain federal recognition. Because a late 19th-century chief refused to sign treaties with a government that ignored agreements it imposed on tribes, the Little Shell were driven from their homes and denied recognition as a tribe.

Members of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians celebrated federal tribal recognition in 2019 with then-Governor Steve Bullock of Montana.

(Montana Governor's Office via Associated Press)

La Tray's travels are chronicled in a series of beautifully rendered chapters in which personal experiences become both a telescope into the past and a microscope on present-day realities. In one chapter, he and his wife offer a ride to a distraught young woman, an account that becomes a history of the role Métis women played as marriage partners, keepers of traditions, and as objects of ridicule by settlers. Racism and misogyny worked in tandem. “The clergy identified all Indigenous women as inherently promiscuous and blamed them for the immorality that was taking place,” La Tray writes, adding that this thinking “remains in many modern communities across the West.” The story has contributed to the continuing genocide of Indigenous women.

In another chapter, in which La Tray details the steps to becoming an enrolled member of a specific tribe, he links the current obsession with DNA ancestry testing to the highly divisive concept of “quantum of blood” the measure of “blood” imposed by white settlers to determine who they categorized as white. Modern and historical versions cause deep divisions among Native communities. Tracing biological ancestry has revealed “suitors” — those who falsely claim to be Native American — but, La Tray says, they could also erase entire peoples with narrow definitions of who belongs.

One of the most remarkable revelations in his memoir is how the process of establishing his identity broadened his understanding that all identity is intersectional. This manifests itself in a variety of ways, but is most clearly brought to light in his acceptance of his father’s denial of La Tray’s ties to the Métis. Recognizing the various identities he contains leads him to recognize that being part of a “landless” people connects him to homeless people everywhere, historically and today.

“Becoming Little Shell” offers readers a detailed history and close analysis of American society, which can be a daunting start. The first few chapters, which chronicle La Tray’s slow process of understanding, feel scattered and disconnected. But the tentative beginning becomes a memoir of profound joy. In acknowledging her and her tribe’s history of repeated trauma, La Tray finds new beauty, like the green shoots and wildflowers that grow after a forest fire. In La Tray’s understanding, trauma is not so much the end as part of a cycle of destruction and renewal.

After formally establishing his membership in the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, La Tray captures one of those moments of joy.

“I take a breath. I am part of this, part of them. I wipe the sweat from my brow and take a quick look around for snakes. Then I follow the trail down the slope, through time, through genocide and diaspora, fear and death and now rebirth, toward food, companionship and, increasingly, community.”

Lorraine Berry is a writer and critic living on Kalapooia land in Oregon. Topics: Lorraine2536