Two years ago, without a single “no” vote among them, California lawmakers passed a law to curb the kind of pay-to-play corruption that has tarnished local governments across the state.

Since then, business groups, campaign donors and local elected officials have attempted to dismantle the law, and this session they pushed two bills designed to do exactly that. Lawmakers should reject any attempt to dismantle the law and instead focus on changes that make it clearer and easier for local officials to comply.

Senate Bill 1439 by Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda) expanded a 1982 law known as the Levine Act, which prohibited appointed members of local boards and commissions from voting on a license, permit or other approval that has a direct financial benefit to someone who donated more than $250 to their campaigns for elected office.

The 2022 bill extended that ban to local elected officials, including members of city councils, school boards, water boards and county boards of supervisors, who had previously been exempt from the Levine Act. The new law required officials to refrain from voting on donor-related matters for one year after their campaign contributions were accepted. They would also have to refuse political contributions from any person or organization for one year after making a vote benefiting that donor.

The goal is to reduce conflicts of interest and pay-for-play politics. The exchange of money between those seeking approval for construction projects or public contracts and those granting approval creates the perception of a quid pro quo, which undermines public confidence in decisions. Strict, time-specific restrictions on accepting campaign contributions and voting on behalf of donors help reduce the perception of favoritism. And it's not a new idea.

The Los Angeles City Council, reeling from a series of corruption scandals involving real estate interests, voted in 2019 to ban campaign contributions from developers with projects that require city approval. The city also bans contributions from registered lobbyists and bidders on municipal contracts.

That's why the vehement opposition to the provisions of SB 1439 is surprising and frustrating. Business groups sued to overturn the lawarguing that it would discourage its members from making political contributions and violate constitutional protections for free speech. A Sacramento Superior Court judge defended the lawnoting that the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized that preventing quid pro quo corruption or its appearance is a compelling state interest.

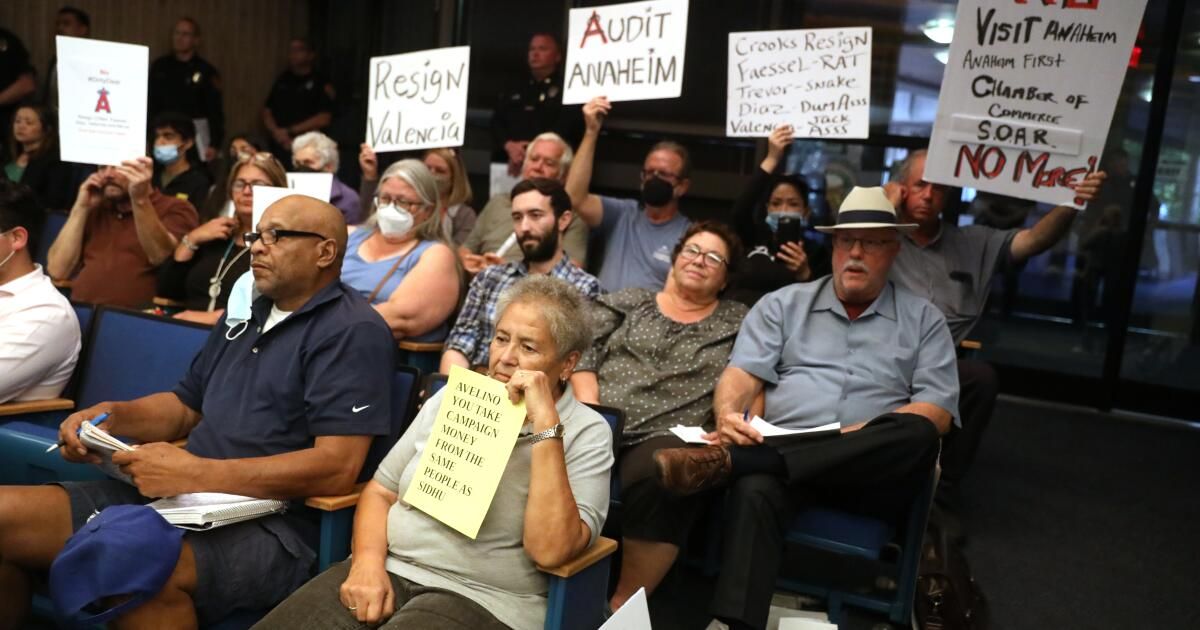

Business groups and some local officials then turned to the Legislature to undermine the law. Government organizations, including the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and the League of California Cities, complained that the law is too broad and the contribution limit too low, and that it has been difficult to enforce.

Glazer and good-government groups supporting the law acknowledge that some adjustments are needed. This year, Glazer introduced Senate Bill 1181 to address implementation issues without undermining the intent of the original law. He also said he is considering raising the $250 contribution threshold for recusal. Supporters, including the California Clean Money Campaign, have suggested that $500 would be reasonable.

Senate Bill 1243 The bill proposed by Sen. Bill Dodd (D-Napa) would shorten the recusal period and raise the threshold to $1,000, which is too high. It would render the law virtually irrelevant in many cities that already limit campaign contributions to levels well below $1,000, so that no donation would trigger pay-to-play protection. An invoice Assemblywoman Tina McKinnor's (D-Hawthorne) proposal would have raised the threshold to $1,500 but thankfully died in committee last week.

Opponents of pay-to-play restrictions argue that the law makes it harder For candidates with fewer financial resources, the law does not limit the ability to donate money to their campaigns, but only to those who have a permit, contract or other decision pending before the local elected body. And if critics of the law say that the only way to finance a city council campaign is to squeeze donations from people who do business with the city, well, that's an argument for public financing of campaigns, not for removing safeguards against corruption.

Trust is essential to a functioning government and is easily lost when elected leaders put their own interests above those of the public. Lawmakers made the right decision two years ago to fight corruption among local officials. They should not change their stance now.