Voters see the economy and inflation as the most important issues facing the country, and despite good news on both fronts, discontent over economic woes remains persistent. There's one area of Southern California where, you could say, it all began: the port and coastline of Los Angeles.

As the hub of American trade in the Pacific and the epitome of buoyant real estate markets around the world, the region's coastal belt sheds light on why so many Americans feel frustrated and under pressure — and how difficult it can be to fix that, no matter who becomes the next president.

Since the mid-19th century, when the United States annexed Southern California to the Mexican Republic, Americans have turned to Pacific trade and western settlement to stabilize their nation. That's why our local ports developed.

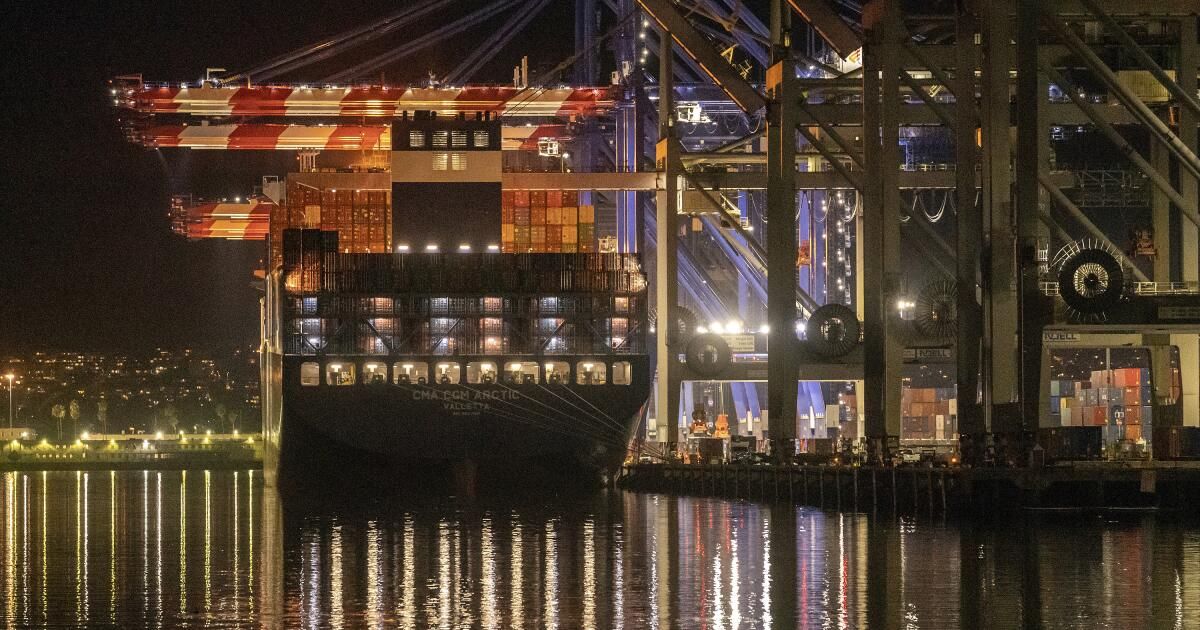

In the 1850s, a federal agency, then called the U.S. Coast Survey, identified San Pedro Bay as a focal point for shipping activities. Since the 1910s, the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach have been located here, together constituting the busiest shipping hub in the Western Hemisphere, making the region prominent in global supply chains and trans-Pacific trade.

Officials believed that trade and settlement in the Pacific would provide an outlet for unrest in the East, particularly over slavery. The results proved them wrong. Trade and settlers escalated political conflict, both in Washington and California, by raising the stakes. Land speculators (who in most places drove out Indians and Mexicans) sought to snap up old ranch grants near prospective California ports in Southern California’s enviable climate. It was a rush for waterfront property such as the region had never seen. Their actions set the boundaries of Los Angeles property and the basis for today’s real estate markets, from Malibu to Newport Bay.

This history was invisible to me growing up in Los Angeles, but its effects were and are everywhere, and continue to transform Southern California in my lifetime. In the early 2000s, container ships, larger than ever before, piled up in the outer waters as ports were sometimes overwhelmed. Semi-trucks clogged the 110 and 710 freeways. At the same time, the coastal real estate market boomed again. My parents, newcomers to the region, found it full of opportunity. They bought their first and only home, in a subdivision on former ranch land, and paid it off as valuations soared around them and their savings grew. The region’s economy was a dynamo, a safe harbor in more ways than one.

Shipping and competitive real estate, two legacies of 1850s Southern California, are still with us. And they are part of an ongoing story about Los Angeles and its place in American life. Today’s voters’ perception of economic well-being is based on the prices of household necessities — mostly imported goods, with about a third entering the U.S. through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Historically, the ships and containers crowding San Pedro Bay have expanded affordability, but the COVID-19 pandemic and international crises disrupted their flow. Suddenly, trans-Pacific trade was blamed for rising costs, not credited for making household goods affordable. Even after the disruption subsided, high prices and memories of scarcity have persisted. Nationally, politicians and the public have come to doubt the virtues of globalization. The clash between high hopes for the Port of Los Angeles and the realities of global trade is once again contributing to Americans' sense of an uncertain world, and once again, the high stakes associated with Southern California's economy are fuelling tensions across the country.

Meanwhile, safe investments no longer make up for hard times. The top investment for Americans, which triumphed in the post-World War II era, is the single-family home. But the country's high real estate prices have upended this convention. Rather than absorbing newcomers and providing a path to financial security, they have multiplied voters' sense of angst by excluding many from the possibility of home ownership. The exultant prices and low interest rates of recent decades—profits and security for earlier buyers—now exert inflationary pressure on renters and prospective buyers, and especially on middle- and low-income or young voters. This is especially true in coastal Los Angeles, west and south of the 405 Freeway. It is true, too, in more distant markets, such as Phoenix and Las Vegas, long shaped by immigrants and money from Southern California.

Southland residents and visitors were drawn to the promise of Pacific waters, as were generations before them. And while many in every era have benefited from the region’s industries and real estate appreciation, many others have always been left behind. Remembering those connections to history can clarify uncertain times. The recent polarization in American politics has been compared to the Civil War era, but perhaps there is a more apt parallel between today and the 1860s: The economic ideas of trade and land investment, meant to calm political passions and spread prosperity, did not pan out in either time.

The consequences will be felt in the coming months, as economic issues are very likely to decide the presidential election. But regardless of the election outcome, we must understand that Southern California is never a place removed from American politics and its dilemmas. On the contrary, these have deep roots in the region. And today, the region continues to invest in imports and real estate as vehicles for prosperity, even as adverse costs pile up in national politics.

That makes Southern California the opportune place to resolve these dilemmas of history and lead America forward, whether through policy experimentation or through new principles for how wealth can be generated, sustained and shared. Shaping a better future for the nation will involve making difficult choices. It will certainly take visionaries and boldness. But that, too, is a legacy of Southern California’s past, one that is ripe for reclamation.

James Tejani, associate professor of history at Cal Poly San Luis Bishopis the author of “A machine to move the ocean and the land:The formation of the port of Los Angeles and the United States.”