Book review

“Playground: A Novel”

By Richard Powers

WW Norton, 400 pages, $29.99

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Richard Powers has long been fascinated by artificial intelligence. Back in 1995, his novel “Galatea 2.2” reimagined the story of Pygmalion from that perspective, and is set in a computer lab at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where the author studied as an undergraduate and later taught. “Plowing the Dark” (2000) presents a twin narrative: the first is about an American hostage in Lebanon who uses memory to preserve his sanity, and the second, about a group of researchers trying to create an immersive virtual environment in a three-dimensional space.

In both cases, the stakes could not be higher: the relationship between memory and imagination, the infinite regenerative possibilities of the human mind and the challenges (or even the obvious risks) of technology. “Playground,” Powers’ latest novel, occupies related territory, moving back and forth between environmental and digital concerns, between the troubled ecosystem of the oceans and the problematic ethics and dislocations of the virtual world. And why not? After all, Powers’s books often read like installments in a long series of narratives, feeding back into one another in a stream of ideas and reference points.

Part of “Playground,” like “Galatea 2.2,” is set in Urbana-Champaign; like “Plowing the Dark,” the novel relies on an interlocking structure, with one thread centered on the French Polynesian island of Makatea and the other told in the voice of Todd Keane, an artificial intelligence pioneer whose Playground project (think a cross between Facebook, ChatGPT and Google, but refracted through a gamer’s sensibility) has made him a billionaire. At the center of the plot, though, “Playground” presents a set of overlapping love stories, requited and unrequited, involving parents and children, friends and, most essentially, humanity and the oceans we’ve studied and fouled.

“The course of civilization is set by currents,” Powers observes. “The global ocean engine determines where sea layers mix, where rains move or wastelands spread, where great currents of water bring deep, cold, nutrient-rich water to the surface bathed by energy and fish go wild with fecundity, where soils become fertile or anemic, where temperatures become habitable or harsh, where trade routes prosper or fail.”

The epic sensibility of this passage recalls Powers’s 2018 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Overstory.” Both that book and “Playground” are what we might call systems novels, a term coined in 1987 by the critic Tom LeClair to describe the trafficking of fiction across social, political or global networks.

Because of its scope (or perhaps its success), “The Overstory” has come to cast a vivid shadow over Powers’s work. Through a fluid sweep of nine characters’ lives, it focuses on the Pacific Northwest logging wars of the 1990s, a tipping point of resistance that allows the author to address the interdependence of humanity and the biosphere. “Playground,” then, might be read as an extrapolation in which it is not the forests (the so-called lungs of the planet) but the oceans (let’s call them the Earth’s circulatory system) that are in danger.

You might think of “Playground” as “The Undergrowth.”

At first, the novel is exhilarating. Powers is a vivid writer, and it can be intoxicating to get lost in his words. “For centuries, my ancestors kept in their heads hundreds of islands spread across several thousand miles of ocean in singing maps,” explains a Makatea artist named Ina Aroita. “All those islands and the paths of all the stars and the swirls of a hundred currents and the behaviors and migrations of all the sea creatures… Now all those maps are gone, and my generation of islanders wanders the beach in a daze, shocked by history.”

What Ina describes is folk knowledge, knowledge of the soul, to which we are all now oblivious, but the brilliance of the passage lies in how the language, its exuberance, embodies what it describes. After all, Ina has also suffered a concussion moving from Makatea to Urbana, where she meets Todd and his best friend Rafi.

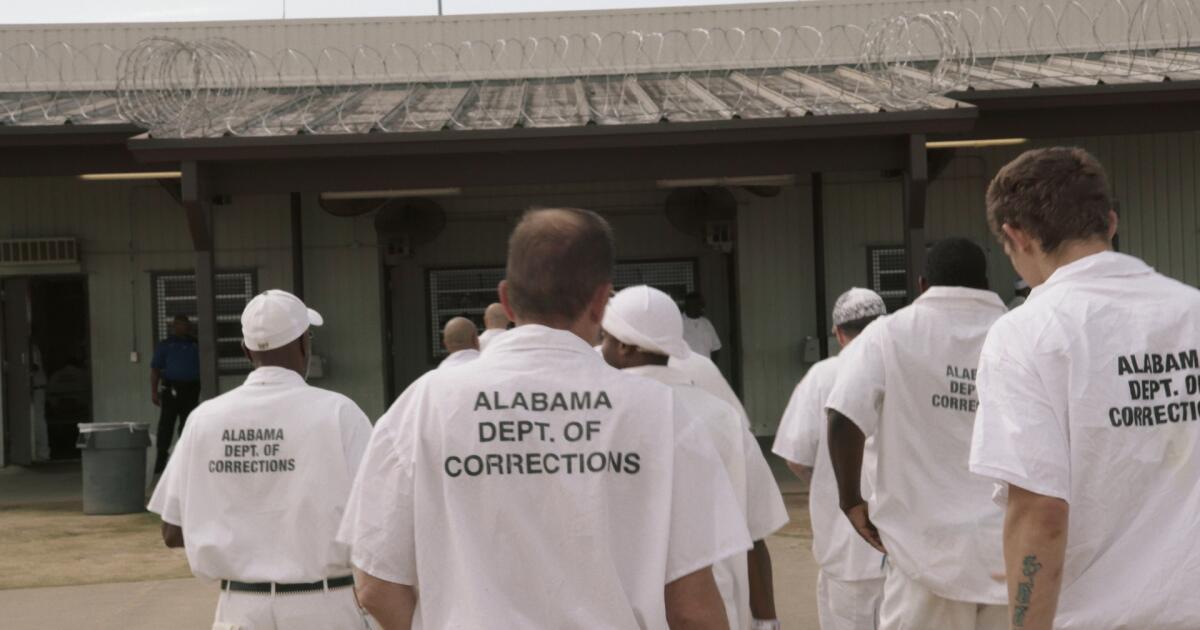

The two men make an odd pair: the first a white boy from Evanston, an affluent suburb of Chicago, the second a black man raised on the city’s Near South Side. What connects them is their love of games: first chess and then, most intensely, Go, the ancient Chinese pastime characterized by its near-infinite options and outcomes. For Powers, these endeavors offer a portal to a new kind of potential, less regenerative than exponential.

As “Playground” progresses, however, it becomes increasingly mired in its polarities. On the one hand, there are the seemingly limitless capabilities of technology, which might even (or so Rafi believes) save us from death. On the other, there is the tunnel vision of the technology’s creators, which more often than not results in exploitation. It’s a rich dichotomy, the kind Powers has already explored in nuance. But here the exploration never comes to three-dimensional life. Even in Rafi’s relationship with Todd, which is partly destroyed by the corrupting influence of Big Tech, Powers remains oddly neutral, even distant.

A similar distance emerges with regard to Makatea, an island that was open-pit mined for phosphate until the 1960s, after which it was virtually abandoned until a shadowy group of Californians proposed reindustrialising it in the service of “seasteading”, a form of eco-colonialism in which modular floating settlements are built and then launched into the ocean. The island’s 82 residents, including Ina and Rafi (whom she has married), put the matter to a vote. Arguments were presented and a decision was made. However, the ethical implications (both of the effect on the island and its culture and of the environmental impact of seasteading itself) remain contentious.

I don't mean to suggest that there are easy answers to these polarities, nor that Powers has to provide an answer. As he himself acknowledges, the consequences are always unforeseen and there is no way to predict an outcome (the world as an augmented reality version of Go).

Perhaps the most vivid representative of this elusive unpredictability is Evelyne Beaulieu, a 92-year-old French-Canadian marine biologist who came to Makatea to end her time on Earth as she began it, in conversation with the deep.

Evelyne is fading. Time has her in its grip. “Memory,” she insists, “should be like a vice in youth, when the emerging navigator needed it most. But no one who has survived to old age has failed to open that vice and let many of the facts she held fast to break free.” It’s not just Evelyne who is losing herself; half a world away, Todd is facing the same hard truth, afflicted at age 57 with Lewy body dementia. The connection (intentional, by the way; for Powers it is, at the very least, intentional) is that Evelyne’s first book, a manual called “Clearly It Is Ocean,” was an early influence on Todd’s thinking about networks, after he read it as a child.

Here, we get a glimpse of how intertwined “Playground” is, with coincidence or serendipity its own kind of web woven beneath the surface, not unlike the turbulent currents of the sea. Still, and unlike, say, “Plowing the Dark” or “The Overstory,” it’s oddly unsatisfying — or perhaps “predetermined” or “calculated” is the more appropriate word. The collapse of Todd and Rafi’s friendship may be inevitable, but it seems like narrative contrivance rather than emotional necessity. The same goes for Evelyne, who reaches an ending that may be consistent with the novel’s structure but seems ungrounded in reality.

“Games now ruled humanity,” Powers writes. “…and it made perfect sense…that the machines that would doom us would be cut their teeth watching humans play.” Still, the novel, like every virtual reality machine, must be a reflection of the world, and in this sprawling parable of a book, which has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, that world and the humans who inhabit it are too often read as failures or archetypes, driven by the hand of the author – or the player – rather than by any organic urgency of their own.

David L. Ulin He is a contributor to Opinion and was an editor and literary critic for The Times.