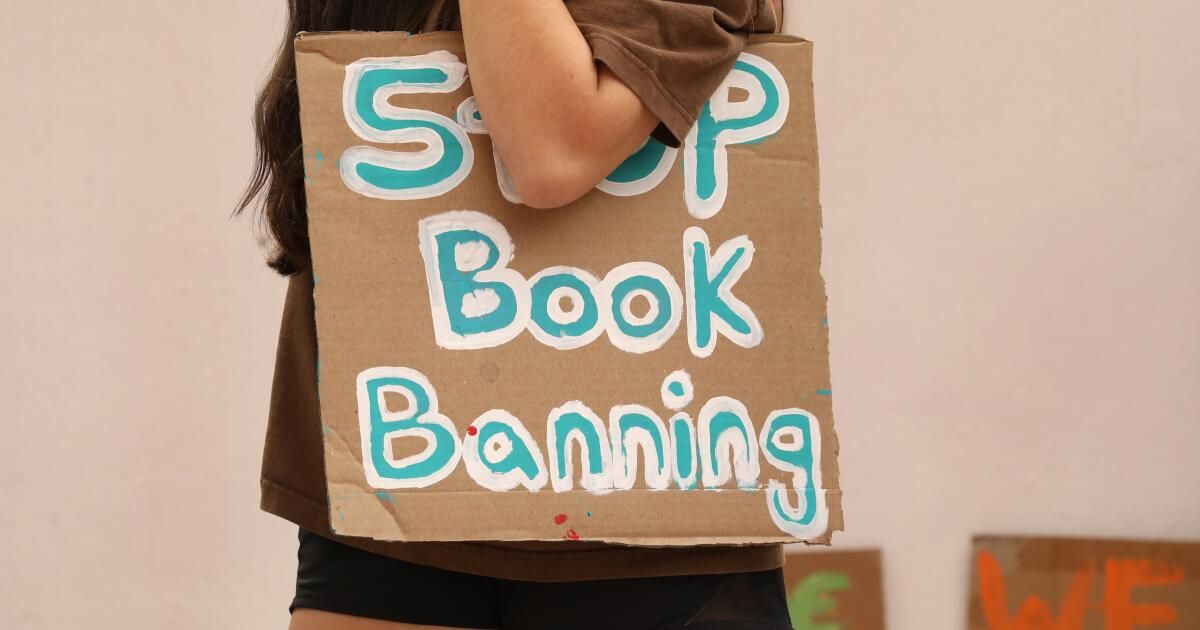

When PEN America emailed me, I was excited. The organization, whose mission is to protect the freedom to write, was looking for volunteers to code banned books. The goal was clear: identify what kinds of information and representation are under attack by censors. Armed with that knowledge, PEN can send free speech and diversity advocates to speak to parent groups, school boards and city councils, to fight to keep books on school and library shelves.

I am a writer. I believe that no book should be banned. There are many that I would not recommend, but I rarely do so because of their content.

Not all books are suitable for all ages, but that is no excuse to turn readers away from good books and good authors, not to mention classic works and great authors. The purpose of reading is to open us up to new things, to meet characters we would otherwise never meet, to discover cultures and entire worlds we cannot imagine. Sometimes that is disturbing, intense or difficult. Sometimes it makes you think. Thinking is a good thing.

I signed up for PEN's codification project. At our training session, I was heartbroken to discover how many book bans have been documented. In 2023, A new record was set:4,349 bans from July to December in 23 states and 52 public school districts—more bans than PEN documented in the entire 2022-23 school year. The list of titles and authors goes on for pages and pages. Some will be rescued in one school district, only to be attacked again in another.

My assignment was to complete a lengthy questionnaire for each of the 30 books I had been assigned. After examining the text and reading secondary sources, I looked at whether the book was fiction or nonfiction, the intended grade or age level, and the setting and genre. Next, I looked at whether it had LGBTQ+, BIPOC, disabled, or neurodivergent characters (as protagonists or supporting characters) and whether it explored themes or metaphors related to those identities. Was race discussed in the book? Did it depict racism? Was it about social activism, immigration, or incarceration?

I answered questions aimed at measuring violence in the books, how sexuality and sexual behavior were portrayed, whether sex was consensual or not, and whether religion, self-esteem, or self-empowerment were central to the plot.

You know where this is going. Books with a queer character, even a minor character, who questions their gender seem to end up on banned books lists.

In Florida, some versions of “The Diary of Anne Frank,” including a graphic novel adaptation, were banned or challenged because they failed to remove passages in which Anne writes about experiments with kissing a girl and her own explorations of her pubescent body. Often, it is the sex, however bland, that makes the books popular.

Censors constantly question the award-winning and successful youth title “The hate you give” In the film, a white police officer unjustly shoots a young black man, and the woman is labeled as anti-police and racist against whites. Should the young witness have remained silent? Should her parents have praised the police officer?

One book on my list didn’t make any sense to me: “A Separate Peace” by John Knowles. It’s a classic, beautiful story set during World War II about friendship, loss, and patriotism. It’s been challenged time and time again. In 1980, the Vernon-Verona-Sherrill school district in New York called it a “dirty, vulgar, sexual novel.” There’s no sex in it. It’s been challenged for its language (less vulgar than anything you hear on TV these days) and negative attitude of teenagers (!!), and because the friendship between Gene and Finny, the main characters, has homosexual overtones. You can read it that way, but that’s your fault, because the author was adamant that his characters are not gay.

““Charlotte’s Web” has been banned, deemed sacrilegious because a spider is smarter than humans. And these classics for slightly older readers are also among those often banished or questioned: “The Kite Runner,” for depicting homosexuality and promoting Islam; “Bless Me, Ultima,” for blasphemy, sex and “anti-Catholic” ideas; “Heart of Darkness,” for racism; and “Brave New World,” for almost everything: “the language of the book and its moral content.”

I read my granddaughter one of the most banned picture books of all time, “And Tango Makes Three,” the true story of two male penguins at the Central Park Zoo who hatched an abandoned egg and together raised the new chick. No matter how many times I read it to her, it won’t make her gay, or turn her into a penguin. It might lead her to a truthful and non-inflammatory insight: there are all kinds of families.

All the greatest writers, from Chaucer to Shakespeare, from George Orwell to JRR Tolkien, from Harper Lee to Toni Morrison, have been banned. As Angie Thomas, author of “The Hate U Give,” saying“It’s an honor to be banned because every book that’s on that list has changed perspectives… it’s changed lives.”

After I finished coding the books on the PEN list, my main thought was not pleasant: envy. My novels are not well-known enough to be banned, not even “Spontaneous,” about spontaneous human combustion, happily incestuous sisters, and sex with a little person. I deserve to be banned. I live in hopes of gaining enough readers to merit banishment. I would be proud to be on the book publishers’ enemies list.

Diana Wagman, a contributing writer for Opinión, is the author of six novels.