On Friday, the Supreme Court once again reduced the government's power to protect the American people from gun violence. In a 6-3 decision divided along ideological lines, the justices invalidated a rule adopted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives that banned a device, stocks, that effectively converts semi-automatic rifles into machine guns. Although the case involved the interpretation of a federal law and not the Second Amendment, it shows us again that the conservative majority on the court will protect the right to bear arms and put lives in unnecessary danger.

A federal statute adopted in 1934 prohibits people from owning machine guns. Congress passed the law because machine guns have the ability to fire many bullets quickly and therefore cause enormous damage. The law defines a machine gun as one that automatically fires “more than one shot, without manual reloading, through a single trigger function.” In contrast, with a semi-automatic firearm, the shooter must release and re-pull the trigger to fire multiple shots.

However, a buffer stock allows a semi-automatic pistol to fire repeatedly, almost at the speed of a machine gun. A rifle equipped with a stock can fire at a rate of between 400 and 800 rounds per minute.

In 2017, a gunman in Las Vegas fired into a crowd at a music festival, killing 58 people and wounding more than 500. The gunman's weapons had stocks.

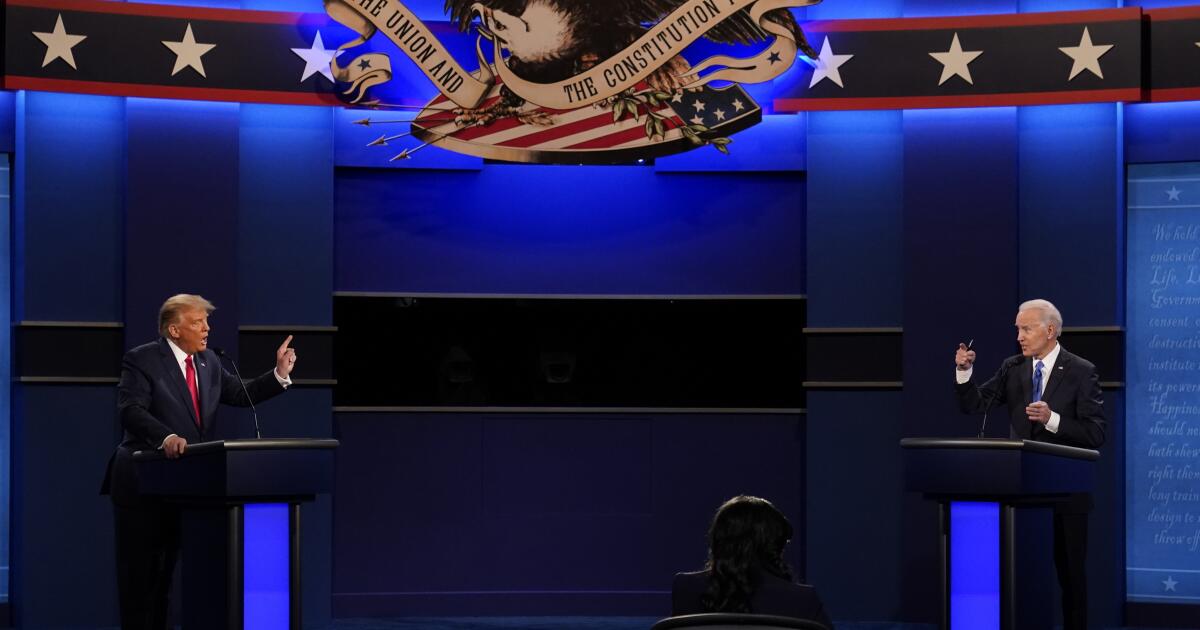

The tragedy in Las Vegas caused the ATF to change its position and consider bump weapons to be prohibited by the statute prohibiting machine guns. It is worth noting that the new rule was adopted by the conservative Trump administration and even the National Rifle Association. agreed regulation was necessary. The rule ordered owners of reinforcement stocks to destroy or surrender them within 90 days.

The new ATF rule made a lot of sense. A weapon equipped with a stock is, for all intents and purposes, a machine gun; Common sense dictates that it should be under federal prohibition. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent on Friday: “When I see a bird that walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, I call it a duck.”

Unfortunately, the court, in a majority opinion written by Justice Clarence Thomas, decided that minimal differences in bump-fire weapons and machine guns meant that the ATF lacked the authority to adopt its standard. A “semi-automatic rifle equipped with a stock does not fire more than one shot with a single trigger pull,” he wrote. “All a buffer does is speed up the rate of fire by causing these different functions[s] of the trigger occurs in rapid succession.”

In addition to discarding common sense, the court ignored the principle that there should be deference to federal agencies, such as the ATF, when interpreting federal statutes. Nor did he follow the principle that laws must be interpreted to serve their purpose.

Both Thomas' majority opinion and Sotomayor's dissent include detailed descriptions of how emergency actions work. Both agree, and it is indisputable, that stocks allow a semi-automatic weapon to function like a machine gun, although the mechanics are slightly, very slightly, different. And it is also undeniable that such weapons can kill a large number of people in a short time.

Why would six Supreme Court justices deny the federal government the ability to interpret federal law to prohibit escalation actions? The only explanation is that the ultra-conservative majority supports the right to bear arms practically without a doubt. They refuse just as steadfastly to acknowledge the enormous cost of gun violence in the United States.

Because this case does not involve the Second Amendment, Congress could adopt a law banning booster stocks. So far, the gun lobby has prevented this from happening. We have to hope that it will not take another tragedy like the one in Las Vegas for Congress to ban a device that serves no purpose other than to effectively convert a rifle into a machine gun.

Erwin Chemerinsky is an Opinion contributor and dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.