The following confession may come as a shock to those who know me: I am now a conservative. When it comes to baseball, that is.

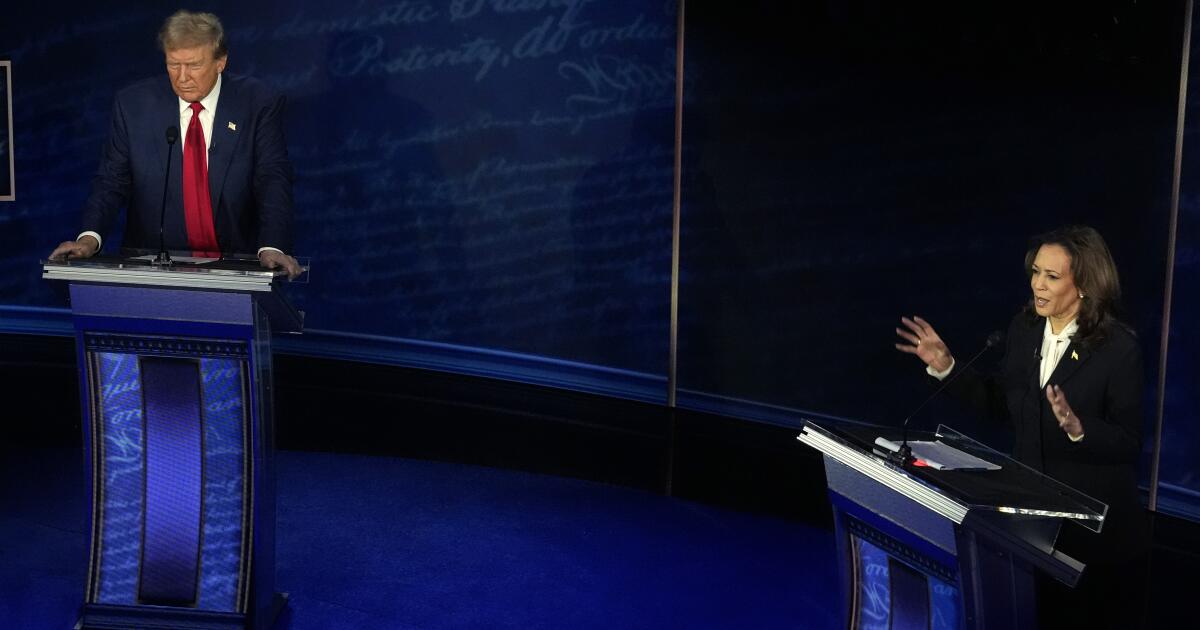

I looked at the failed check-swing that allowed the Dodgers to win a game against the Rockies last month in an improbable comeback and to the fury of Colorado fans. The umpire's clear error will only increase demands that check-swing calls be included in the instant replay protocol.

But subjectivity in swing control is a fundamental part of the way baseball is supposed to work: humanely, in a sublime, sometimes maddening imperfection. MLB’s interventions to “fix” it — bigger bases, the phantom runner on second base in extra innings, hitters limited to one timeout per at-bat and, worst of all, the pitch clock — are blows against the beauty of the game.

It's true that these changes seem to be quite popular. Games have gotten longer and longer with incessant pitching changes, batters being delayed, and, yes, play reviews. But what monstrous arrogance to think we know more than the original founders of baseball! Ninety feet between bases, 60 feet, 6 inches between the pitcher's rubber and home plate: these are divinely induced measurements. If you start messing with tradition, the heart of the game gets lost in the hyper-regulated “reality.”

Baseball is not reality. It is a myth played out by real bodies. And imperfection, which is also the unexpected, beyond the reach of metrics, is where magic comes from: magical triumph and magical heartbreak, larger than life, operatic.

There is no doubt that football is the “beautiful game,” but baseball is a competitor. Its very beauty is the result of the gradual accumulation of tradition, which has given us a poetics.

Languor is one of the essential characteristics of baseball. Nothing seems to happen for long minutes; no one scores, no double plays with a bang-bang twist, only weak fly balls and dribbling ground balls; the lullaby of sunshine and beer lulls you into a state of somnambulism.

And then, “just like that,” as Vin Scully would say, comes a majestic home run, a spectacular catch, a ferocious duel between pitcher and batter, a spectacular strikeout. The explosion of affection is all the more powerful for having emerged so suddenly from the caesura. (Football fans experience a version of these symphonic shifts of rhythm on the field.)

The temporality of baseball is inseparable from its physical dimensions, the space-time of the game: the vast stretch of grass between the outfielders, the tighter spaces between the infielders, the concentration tunnel that connects the pitcher, the batter, the catcher and the umpire.

The imperfection of referees is indispensable to the gestalt. Video appeals deprive us of the opportunity to yell at the referee to get some glasses, or suffer much worse. A wrong decision can lead to simultaneous jubilation and heartbreak, with the losers tearing their clothes and smarting from the insult of having been “robbed.”

Everything as it should be.

I say: Bring in smaller bases and keep stealing a base, a rare art! I say: No more ghost runners (what did he do to deserve to be there?) and keep playing all night with drunken players if that’s what the game demands. And above all I say: smash the pitch clock with an Adirondack bat. The stopwatch is an abomination under the baseball sky, depriving us of the organic crescendo of tension in an epic at-bat in the late innings of a close World Series game (Kirk Gibson, 1988).

When I interviewed Scully after the 1992 Los Angeles riots, I asked him what he had said on air about the chaos that erupted that first night, while a game was being played at Dodger Stadium. “I didn’t say a word,” he said. He thought first about his responsibility to the fans and their safety: What if he caused a panic? He added: “There should be a place where the rest of the world doesn’t interfere.”

He might as well have said that baseball is sacred and that no one should mess with it. Not even (as if that were possible) history itself.

In all this, I consider myself much more conservative than, say, old-school traditionalist and bow-tie George Will, who for once approves of “progressive” in the form of the new rules that he believes herald a return of baseball to its former status as a national pastime. The game, awash in game metrics, Will has arguedIt is not bloated by poetic languishing but by analytical boredom.

That's true, Mr. Will. We agree that baseball is slowly dying by the numbers. In the end, all the measurements don't reflect what's essential: the ineffable beauty of a summer afternoon that slowly turns into night at the ballpark.

Some of us know when the cure is worse than the disease.

There's a reason baseball was famous as the favorite sport of American writers In the mid-20th century, the clock was not part of poetry.

Rubén Martínez is a professor of literature at Loyola Marymount University, the author of numerous books, and co-creator and executive producer of the stage piece “Little Central America, 1984.”