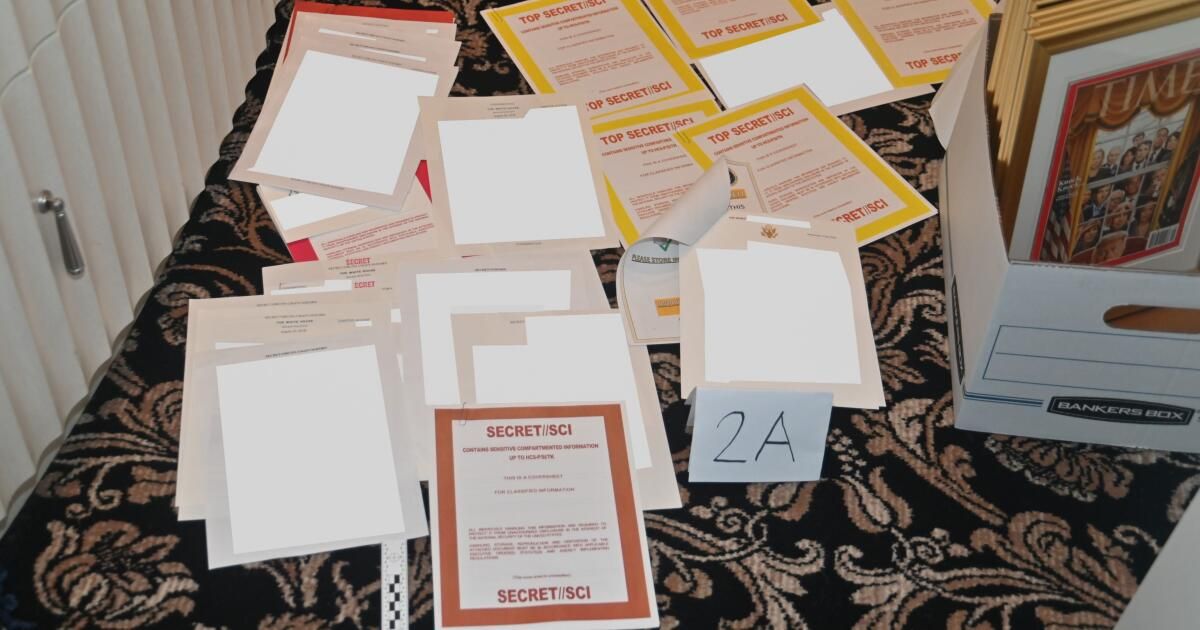

Judge Aileen Cannon's stunning ruling dismissing the federal indictment against Donald Trump for mishandling classified documents is simply wrong as a matter of constitutional law, but it can easily be overcome.

Cannon argued that it is unconstitutional for the attorney general to appoint a special prosecutor to handle a prosecution unless there is a specific law authorizing it. The simple solution is for Attorney General Merrick Garland to treat the classified documents case as a crime like any other, which does not require a special prosecutor. He can order a U.S. attorney to immediately refile the case in federal court, and, by Cannon's reasoning, there would be no constitutional problems.

From the beginning, Cannon, who was appointed by Trump to the federal district court bench, has handled the case in a way that seemed designed to protect him. For example, she had previously ruled that a higher standard had to be met to justify a search warrant against a former president. The federal appeals court reversed this decision, saying the same standards apply to everyone under the Fourth Amendment.

In addition to saying that the attorney general cannot appoint a special counsel and shield him or her from impeachment, Judge Cannon also said that it is impermissible for the Justice Department to fund a special counsel on an ongoing basis.

Judge Cannon's decision on Monday is completely wrong because it is inconsistent with U.S. Supreme Court precedents and the rulings of many other courts.

The crucial problem is that under Article II of the Constitution, the Attorney General, like all Cabinet officials, can appoint and fund “inferior officers.” The statutes give each chief of staff broad authority to make such appointments.

The Supreme Court said all this explicitly in United States v. Nixon in 1974. A unanimous Supreme Court declared: “Congress has also invested [the attorney general] the power to appoint subordinate officers to assist him in the performance of his duties.” The court explicitly held that the attorney general could appoint a special prosecutor to investigate crimes arising from the 1972 presidential election and allegations involving President Nixon.

Cannon said that this was simply a “dictation” by the Supreme Court, unnecessary language for its decision, and that she was not bound by it. Quite the contrary, if the Supreme Court had reached Cannon’s conclusion, it would have had to dismiss the case before it.

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia has repeatedly addressed this issue and reached the exact opposite conclusion to Cannon.

In 1987, a constitutional challenge was filed against the special prosecutor who investigated the Iran-Contra scandal during the Reagan administration. The federal appeals court said: “We have no difficulty in concluding that the Attorney General possessed the statutory authority to create the Office of the Independent Prosecutor: Iran/Contra and to transfer to it the ‘investigative and prosecutorial functions and powers’ described in… the regulations… [the specific statutes] “While they do not explicitly authorize the Attorney General to create an Independent Prosecutor’s Office virtually free of permanent oversight, we interpret them as an accommodation to the delegation at issue here.”

In 2019, a very similar challenge was raised to special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. Again, the federal appeals court said the attorney general had the authority to make and fund the appointment. And last year, a federal court rejected the same constitutional challenge to the special counsel who was prosecuting Hunter Biden. Cannon’s ruling simply says that he believes these courts got it wrong.

Cannon also argues that the Justice Department cannot fund a special prosecutor on an ongoing basis. Each department has discretion over much of its budget. In fact, in the last term, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and highlighted the flexibility the Constitution provides for funding federal activities.

What makes Cannon's decision dangerous is that it would remove a crucial tool for allowing the Justice Department to conduct prosecutions that are independent, and appear independent, from political control, given that the attorney general is a presidential appointee.

Following Watergate, Congress passed the Ethics in Government Act to create special prosecutors who could only be removed for cause and who were completely independent of the attorney general. In 1988, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of this act, but after several lengthy investigations, including the Whitewater investigation of President Clinton, the act was allowed to lapse and was not renewed.

A new mechanism was created to allow for independent, but more accountable, investigations. The attorney general appoints the special prosecutors and, through internal Department of Justice regulations, guarantees their independence. This gives the public confidence in the investigation that would not exist without that independence, which is particularly desirable when the person under investigation is a president or former president or one of his or her relatives or a high-level government official. Because of Article II powers, this mechanism, like the previous law, is constitutional.

Special counsel Jack Smith could appeal Judge Cannon’s decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit, but that process will take months and will ultimately likely end up at the Supreme Court. The expedited solution for this case is for Attorney General Garland to get the Justice Department, through a federal prosecutor, to refile the indictment against Trump. This would avoid Cannon’s trouble with the special counsel.

Erwin Chemerinsky is a contributing writer for Opinion and dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.