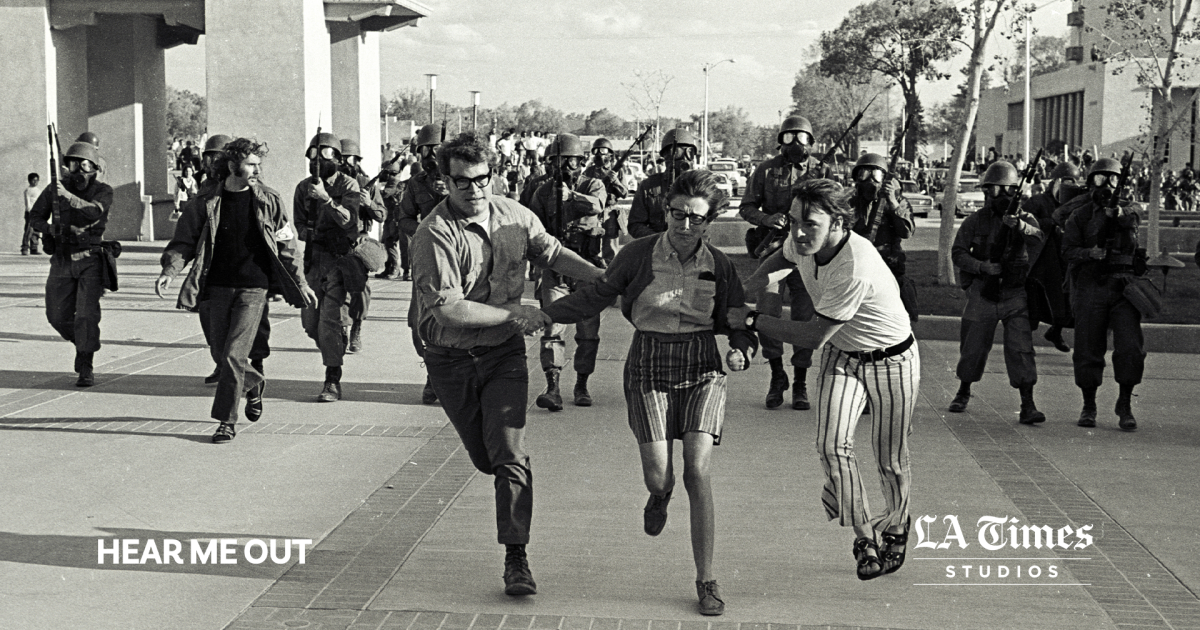

The Los Angeles city government has a corruption problem. Since 2020, three Los Angeles council members and a former deputy mayor have been convicted or found guilty of charges such as bribery and lying to authoritiesAnother board member has been accused of embezzlement, perjury and conflict of interest, and yet another is accused of violating city ethics laws. During the same period, three other council members (including a former City Council president) They were recorded making racist comments as they discussed how to manipulate municipal districts to their advantage.

This cascade of scandals has eroded trust in local government. Now the City Council is considering charter reforms that would give new powers to the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission. The council should be commended for addressing its corruption problem. However, the proposed reforms are inadequate.

What is offered has positive points: the reforms include expanding the number of members of the Ethics Commission, establishing a minimum budget for it, and increasing sanctions for violations of the Los Angeles Code of Ethics. But the overall package is not ideal because the City Council will not give up enough power to ensure the commission has the independence it needs to do its oversight work.

Specifically, the proposed charter amendments do not give the Ethics Commission authority to place ordinances related to its mandate directly on the local ballot, without the City Council having the final say.

That kind of independent power has worked well in San Francisco. In the decade 2013-2023, in response to government scandals, the San Francisco Ethics Commission placed two ethics-related measures on the local ballot. Both passed by significant margins. Those two measures represented just 2% of all San Francisco ballot measures during that period. In other words, the SF commission has not abused its authority to independently update the city's ethics laws, as some Los Angeles council members fear will happen in Los Angeles.

Giving the Ethics Commission the power to go directly to voters would not prevent the agency from first engaging with the City Council to achieve its ends. In fact, that would be preferable: Angelenos' elected representatives should be able to weigh in and reach an agreement with the commission to fix flaws in ethics laws as they arise. But if the council and commission can't find common ground, commissioners need the option of putting an ordinance on the ballot.

In other words, ballot placement would be an action of last resort, a lever to help the council properly address the city's ethical issues.

Unfortunately, the proposal that the full City Council will vote on only this week aspect as if it provided a way for the Ethics Commission to recruit voters against a recalcitrant council. The legal loopholes are gigantic.

First, the charter amendments would allow the commission to place ordinances on the ballot only if the council ignores their proposals entirely or disapproves them without any amendments. If the council accepts a commission proposal and waters it down or even guts it with amendments, the commission would have no recourse. Worse yet, if the council ignores or votes no on an ethics reform, and the commission decides to bring it to a vote, the council could veto that decision.

This is far from the tried and true San Francisco model, and is not likely to result in changes that strike at the heart of corruption: consolidated power and inaction on reform.

The barrage of scandals at Los Angeles City Hall has created a once-in-a-generation opportunity to clean up Los Angeles government. It should not be wasted with half solutions. The reform package passed by the City Council, which will have to be approved by voters in November, should give the Ethics Commission the independence it needs to hold officials accountable to the people they represent.

To face the moment, the City Council must give up power for the greater good.

Sean McMorris is the director of California's Common Cause program for transparency, ethics and accountability.