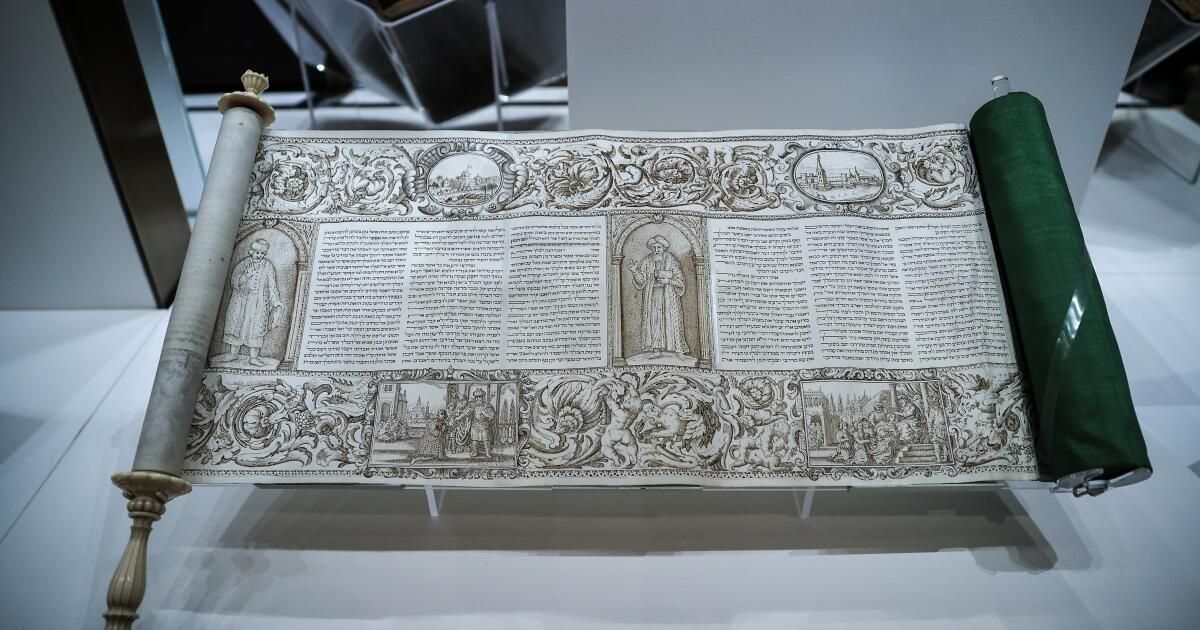

In a few days, Jews will gather for the holiday of Purim and read aloud from the Book of Esther. A month later, another meeting, another book: the Passover Haggadah. These ancient texts speak to us across the centuries, a conversation at once illuminating and intermittent, bringing the past into the present in ways that are reassuring but also uncomfortable.

This year I feel the discomfort a lot. Since Hamas launched its horrific massacre and hostage taking on October 7 and Israel retaliated in a brutal, ongoing war, the texts seem prophetic and agonizing, more disturbing than ever.

The Book of Esther and the Haggadah were written in response to trauma, which may have been historical or mythical, but ultimately the difference between historicity and mythology does not matter here. Centuries of interpretation invite us to read the words and lessons of texts through the lens of our own experiences and sensibilities, much as most Americans read the United States Constitution and other similar founding documents. We highlight what resonates for us and deny or minimize the parts that make us cringe, but dealing with text is very human. And very, very Jewish.

Purim falls on March 23 and 24 this year, when Jews commemorate what is generally considered a story of joyful triumph of good over evil. Esther, a beautiful maiden who hides her Jewish identity, becomes a king's favorite and bravely takes advantage of her proximity to inform him that her henchman, Haman, wants to destroy her people. Led by her uncle Mordechai, Esther prevails and Haman is destroyed in the Jews' place. This is a rare diaspora biblical text (the events take place in Persia (outside the Holy Land)) and presents a woman as the savior of an oppressed minority, able to muster the courage to move from powerlessness to power. God is not mentioned even once in the Book of Esther; It is a story driven by human action.

It resonates today in the heartbreaking aftermath of the October 7 attack. If only An Esther could have prevented the massacre and kidnapping. If only an enlightened monarch could have stopped the rape and killing. Haman. Hitler. Hamas. All eerily intertwined.

But as we relate to victimization, we must also recognize and relate to the revenge taken. by the Jews. The ninth chapter of the Book of Esther, often read quickly as if it were an afterthought, details a violent episode of state-sanctioned retaliation, when Jews murdered 75,000 Persian “enemies,” including women and children, and They rejoiced afterwards.

Not only was Haman executed, but at Esther's request and with the king's acquiescence, so were his ten sons. The text says that many Persians were so afraid of the newly militarized Jews that they also professed to be Jews.

For centuries, rabbis and scholars have tried to justify this problematic spasm of violence. Maybe the death toll wasn't 75,000. Maybe they didn't kill women and children, even though that was explicitly allowed. Perhaps all of this was necessary self-defense.

I find these rationalizations unsatisfactory. The ninth chapter seems to me to be a warning of the extremes to which a previously oppressed people will go when presented with a rare opportunity to exercise their political and military power. It uncomfortably echoes the Israeli attack on Gaza today, with entire families wiped out, hunger and displacement rampant, thousands of children killed and orphaned, and cities virtually destroyed. Does one trauma justify another? When does self-defense become revenge? How do you weigh proportionality during what is today an existential crisis for Israelis and Palestinians?

There is an equally uncomfortable section of the Passover Haggadah, read each year at the Seder table. Its location in the second half of the Haggadah (after the matzah ball soup, brisket, and macaroni have been happily consumed) means that many Jews simply skip it. But those who take the text seriously must deal with the shfokh hamatkha, a prayer that asks God to “pour out your wrath” against Israel's enemies. While the revenge sought on Purim is committed by humans, this prayer asks for divine retribution – more abstract and even more powerful – and appears after the part of the Passover story where the Israelite slaves have been freed.

For centuries, Jews have been bothered by shfokh hamatja, so much so that an alternative wording (“pour out your love”) appears in some versions of the Haggadah. But like the ninth chapter of Esther, this text gives voice to a malevolence in Jewish tradition that makes me shudder, highlighting an unfortunate characteristic of human behavior, inviting us even today to plead with God to pursue and destroy our enemies.

And yet, as my friend Rabbi Richard Hirsh tells me, “eliminating unpleasant things does not make the emotional impulses behind them disappear. He just avoids them. The most important question is: what do we do with the ugly things in our tradition? And not only our tradition. Is it better to read it, contextualize it, debate it? Or avoid it and hope no one notices?

Earlier in the Haggadah, there is another disturbing account, taken from the biblical book of Exodus, of the ten plagues that God directed on the Egyptians as a show of force to persuade Pharaoh to free the Israelites. But as the plagues are recited, a little wine is poured out for each one.

What I was always taught, what I believe today, is that we reduce our wine to diminish our own joy because of the suffering experienced by the innocent Egyptians as God's punishment reaches a crescendo, before Pharaoh finally lets go of the town.

This warning to recognize the pain and destruction suffered by our enemies and temper our own sense of vindication is instructive, important, and even comforting. It demonstrates how these foundational texts give voice to our impulse for revenge and also provide a roadmap for empathy. In this, they are not simply stories of the past but necessary lessons for the present.

Jane Eisner is the former editor-in-chief of Forward, a national Jewish news outlet, and former director of academic affairs at the Columbia Journalism School. She is working on a biography of Carole King.