In 2018 I became a one-way pen pal of democracy, writing letters and postcards to strangers in the run-up to that year’s midterm elections.

I had spent the previous months marching for women, science, immigrants and Muslims. Then I decided that marching wasn't enough. I needed to involve individual Americans in electing politicians who shared my values.

In September, I attended a grassroots event to learn about voluntary voter outreach organized by a Los Angeles group called Civic Sundays. We could choose to learn how to knock on doors, call and text potential voters, or write postcards to engage with people.

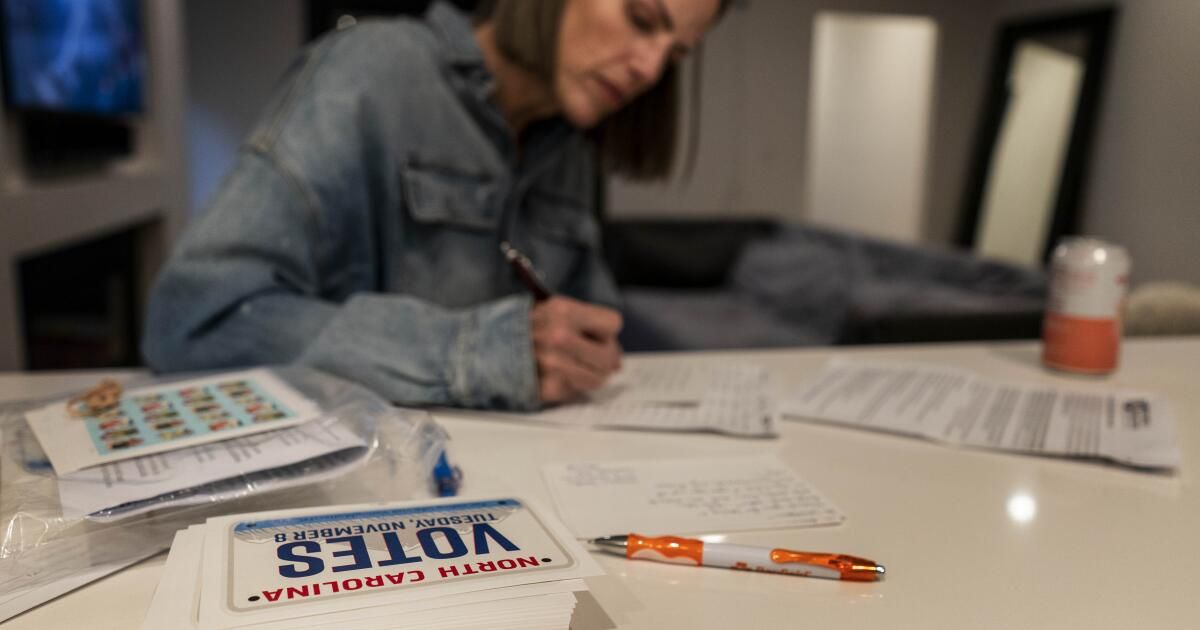

I had never heard of writing postcards to strangers as a way to encourage them to vote, but I loved the idea of an analogue medium to save democracy. Civic Sundays and other organisations, many of which sprang up in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, provide volunteers with lists of names and addresses of registered voters. Writers provide handwriting, stamps and sometimes the postcards themselves.

I joined a large table of people who apparently had professional skills with marker and glitter. While their postcards looked like illuminated manuscripts, I worked hard to make mine legible. A fourth-grade teacher once told me that my handwriting looked like a kidnapper's ransom note, but fortunately I didn't have to take a handwriting test to get a spot at the postcard table (some organizations do require this).

I thought it was a pretty healthy job, but I wasn't convinced by the idea of trying to involve a population that didn't want to vote.

The more I wrote postcards, the more I wondered: Who were these infrequent voters? Why were they not doing their civic duty? If I looked up their address on Google Maps, what would I see? Unmowed lawns? Boarded-up mansions?

I was overcome with the desire to know who exactly these civic evaders were, but we had been given clear instructions: not to make personal contact with the recipients of our letters. Instead, we followed a clear and concise script of just a few sentences.

I participated in another postcard-writing campaign for the 2020 presidential election. This time, I specifically asked for names from a key state, Michigan. As I wrote to these strangers, I grew increasingly frustrated, imagining them enjoying their weekends without a shred of guilt for having voted, while I agonized over whether they would be offended by a postage stamp featuring a cat.

When I mentioned these frustrations to a cynical friend, he told me to read the Trappist monk Thomas Merton’s famous 1966 “Letter to a Young Activist.” I should have been suspicious, since my friend would be the last person to write a postcard to a stranger. Sure enough, Merton’s words did not reassure me about the fate of my postcards.[D]“Do not depend on the hope of results,” he wrote. “When you are doing the kind of work you have taken on, essentially apostolic work, you may have to face the fact that your work will be seemingly useless and even yield no results at all, or perhaps results opposite to what you had hoped for.”

After reading Merton's letter, I spent a few months No writing to delinquent voters in Michigan, Georgia, Arizona, or anywhere else.

But when the 2024 election campaign began, with the future of the country once again at stake, I asked for another list of postcards.

This time, one of the options was to write to people in my own state, California. It felt more like writing to a neighbor than to someone far away and completely unknown. Once I had my list and started reading the names and addresses, I realized that some of my postcards would go to people who lived near the city where I work.

And then it happened. I recognized a name. The Gen Zer who needed a nudge to vote was one of my thoughtful, capable students.

I finally got a response about the people I was writing to. They were just like the rest of us: singles and matriarchs of large families, people who drive electric cars and people who drive big trucks, lovely people and irritating people and neighbors who play music too loud but are sweet to their kids. People so busy with their lives that they sometimes forget or choose not to vote.

Recognizing just one name made me certain that I must continue to write these epistles of democracy, to remind others, even if they did not listen or did not want to hear them, that their vote mattered. With a new understanding of Merton’s famous missive, I had to place my trust in, as he said, “the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.”

Melissa Wall is a journalism professor at Cal State Northridge who studies citizen engagement with news. This article was produced in collaboration with Zócalo Public Square.