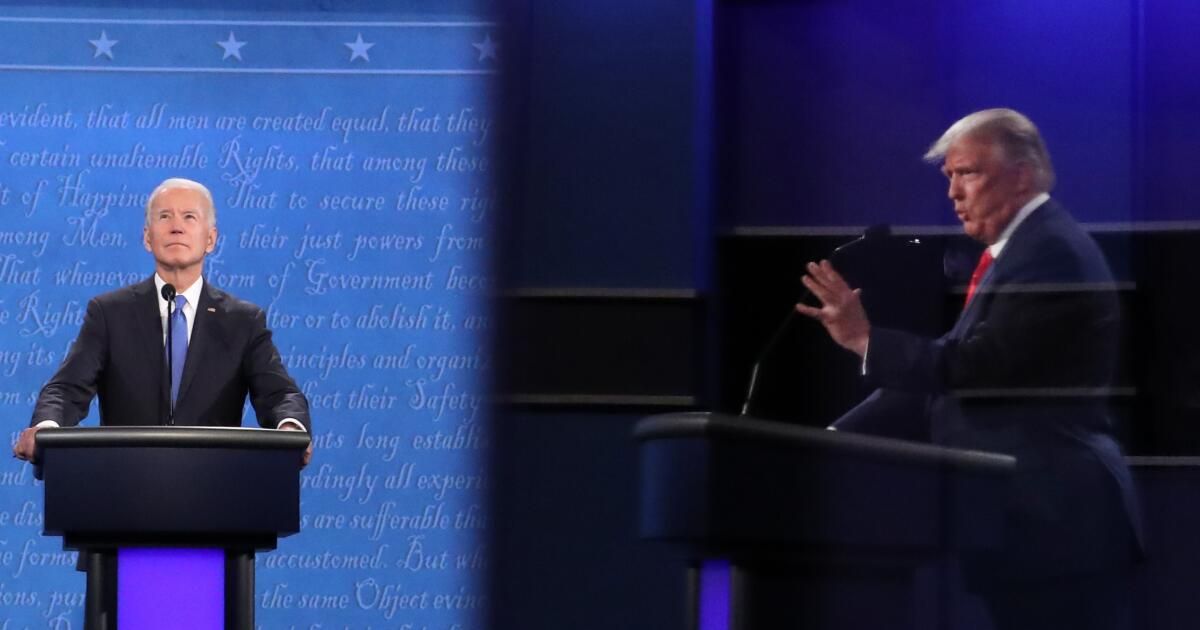

A new phase of this election season will begin Thursday as President Biden and former President Trump face off, and the blame game is sure to be part of the spectacle. Presidents are blamed for almost everything that happens during their time in office. But in reality they are not responsible for so many things that voters, journalists or political opponents try to blame them for.

The public demands action and the candidates promise it, but the presidency is an impossible position. It combines excessive expectations (which the presidents themselves have embraced by campaigning as the voice of the entire country) with very limited political power in a system that is currently characterized by stagnation. Neither Biden nor Trump is likely to take office in January with a majority in the House and a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate. And the public pays little attention to the area where presidents have the most direct authority: foreign affairs.

Instead, in the debates, both candidates are likely to talk about their economic backgrounds and make promises about what they would do in a second term. But the economy is a complicated picture. Unemployment is low, the stock market is doing well, and inflation may be under control. Consumer confidence is rising, but that change has not translated into a more favorable view of Biden. This may be because grocery prices have not dropped, so higher prices are on voters' minds. According to Gallup polls, the high cost of living is by far Americans' most pressing financial concern.

Voters tend to blame the incumbent president and his party for economic problems. Credit for good times doesn't always flow the same way. Shouldn't history tell us whether presidents are responsible for the direction of the economy? While some studies have found that the economy performs better under Democratic administrations, one study concluded that partisan differences in economic performance do not stem from different political approaches but rather from factors such as oil crises, growth in defense spending and greater economic growth abroad.

A decade ago, a colleague and I discovered that gas prices, foreclosure rates, and local unemployment levels in a community of voters influenced their perceptions of the national economy, which in turn affects the vote for president. Factors such as local unemployment, federal spending in the community itself, and federal response capacity after a natural disaster drive support for incumbent presidents in affected communities.

This research helps explain why Americans may not broadly agree about how well the nation is doing and whether Biden should be blamed or credited for the direction of the economy. Partisan polarization also leads some voters to set aside their own knowledge and experiences and blame the president, or a candidate, for almost anything.

Voters also change their opinion of presidents due to events that are far beyond the president's control, such as when a local college football or basketball team wins a game just before an election, or even the occurrence of a natural disaster. One study even found evidence that voters blamed President Wilson for the shark attacks off the coast of New Jersey in 1916.

Here's another thing presidents can't control: the weather. In 2012, Superstorm Sandy hit the East Coast in late October, when the presidential campaigns were in their final stages. The storm gave current President Obama the opportunity to be seen coordinating the federal response, comforting affected communities and meeting with Republican and Democratic leaders. Some research shows that Obama received votes based on his response to Sandy.

Presidents cannot control natural disasters, but they do decide how to respond, sometimes demonstrating leadership and even bipartisan cooperation. These responses can reveal information about the quality of an elected official and potentially influence votes.

The election could be influenced more by a random act of Mother Nature in the fall than by a debate in June.

Andrew Reeves is a professor of political science and director of the Weidenbaum Center for Economics, Government and Public Policy at Washington University in St. Louis. This article was prepared in collaboration with the conversation.