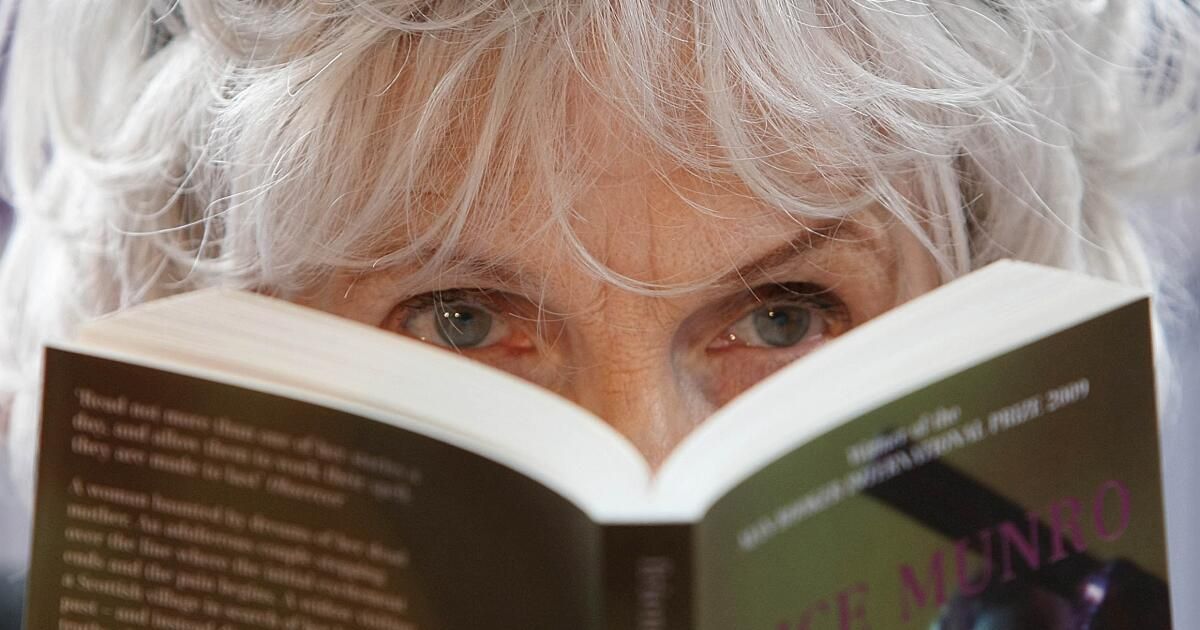

I was 15 (a Canadian kid growing up on a diet of my country's many notable authors and an aspiring writer) when I first read Alice Munro's “The Lives of Girls and Women.” I leafed through that small volume of stories with the supreme arrogance of youth. I remember thinking something like this: Women's lives are nothing like that.

Less than two decades later, I would close the last page of that same book with a shudder, thinking to myself: Women's lives are exactly like that.

Alice Munro, who died on Monday aged 92, saw our lives very clearly.

Why did it take me so many years to understand the stories about women Munro had to offer? My youth began in the 1990s, at a time when young women were assured they could be anything. Wasn't gender inequality yesterday's news? Surely the fact that Munro was a famous writer was proof that the complex problems he wrote about were naturally becoming a thing of the past. He could appreciate the creative genius of his abilities, but if women's lives were such a problem, he was sure the problem was already solved.

At some point in my 20s, I began to realize the complete deception of this view. I began to read it seriously, this time with a certain humility. In their stories, I saw the lives of women I recognized: the college degree my grandmother longed for but she was never able to obtain, the career as a television producer my mother gave up when she married, the unequal power men wielded in the workplace. world. And I also saw my doubts, my relationships with decent, sometimes very damaged men, the conflict between my dreams for my own life and the competing demands of my own family. These things were almost indescribable; They were as difficult to characterize as air. But Alice Munro made them real, and somehow the fact that these quiet revelations took place in parts of Canada I knew made them even more real.

Later, I saw their stories reflected in the mirror of the lives of my patients, older women of Munro's generation who enthusiastically confided to me how happy and relieved they were to have a woman as a doctor. They often confided to me the same kinds of stories that Munro naturally told, those that had seemed fantastic or exaggerated to me before I began to understand the lives of girls and women.

I once asked a patient in her 80s about the origin of a weak, knotted scar that ran along the midline of her lower abdomen. She told me that she had had a cesarean section performed when her only living child was born. Then, almost as an afterthought, she told what was practically a Munro story: she had once given birth to a stillborn child. That day she had gone to milk the cows in the barn and had worked harder than expected. The next day the baby was stillborn. She had carried that weight for 60 years. She had always blamed herself for the loss of that child, for being, as she told me in a low voice, “a damn fool.”

Munro's stories often have the same kind of dark turns. They are full of necessary revelations: about marriage and sex, childbirth and death, fidelity, recklessness and desire. But often their central events are private revelations, small but important failures, confessed to the reader or some third party much later in life. And perhaps most importantly, her writing invites compassion for her narrators, who are often unable to muster it themselves.

By inviting that compassion, perhaps their stories also opened the door to a crucial question, one that occurs to me only now. If we see ourselves in those narrators, aren't we obligated to also have some compassion for ourselves?

Not all of Munro's stories were about disasters. Many of his best and unforgettable works are about grenades that only briefly lost their shafts, the grace of the moments when a split second, good instinct or a stroke of luck protects a protagonist from catastrophe. These are moments when the children could have drowned but didn't, moments that seemed primed for violence, until the storm cloud silently passed and headed elsewhere.

That's the life of a woman too, right? The constant and necessary surveillance in the face of possible disasters. If disaster never occurs, a man can say that all that fuss was simply neurotic. But that is a view from outside fear, formed after the danger has passed. The ever-present threat of what could It happens, wherever you are, whether crossing the street or the Atlantic: that tension defines a woman's life. Of course, not just a woman's life: men feel it too. But she is inseparable of a woman's life, because women's lives often consist of taking care of everyone except themselves.

There is a line in Munro’s story “Wood” and it is one of my favorites in all of his work. A man named Roy is cutting down trees and walks into a hole. When he realizes that he is about to fall and break his leg, Munro writes: “What happens to Roy now is the most common and yet the most incredible.”

I think about that line all the time. Tragedy is a common event in human history, and it is only incredible when it happens to us. A writer who wants to take us to that tragedy has to take good care of us. That's what Alice Munro did. And she made it look incredibly easy, dissecting that plane between the ordinary and the incredible as expertly as any surgeon. She showed us life as a series of moments that can cradle us or betray us, full of endless, undulating aftermath, the miraculous banality in the days we rearrange over and over again before, one day, we die.

That's how I felt when I heard about Munro's death, which was no surprise at the age of 92. The most common and the most incredible. It describes what happens every day in a hospital and, hopefully, in a few days of our lives. And it is also the space where the best writers in the world live.

Jillian Horton is a writer and doctor. Her first book, “We're All Perfectly Well: A Memoir of Love, Medicine, and Healing,” is being adapted for television. @jillianhortonMD