To the editor: As a displaced resident of Palo Verde – one of the neighborhoods cleared in the 1950s on the current site of Dodger Stadium – I do not support Assembly Bill 1950, the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act. But I do support justice and government accountability for families displaced by the city of Los Angeles. (“What does Los Angeles owe to the people who lost their homes in Chavez Ravine? More than an apology,” editorial, May 9)

AB 1950 would require Los Angeles to create a nine-person commission chosen by politicians. It would be up to the newly created commission to determine who would qualify for compensation, a daunting task considering the number of children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. This is likely to cost millions of dollars before a single penny reaches their descendants.

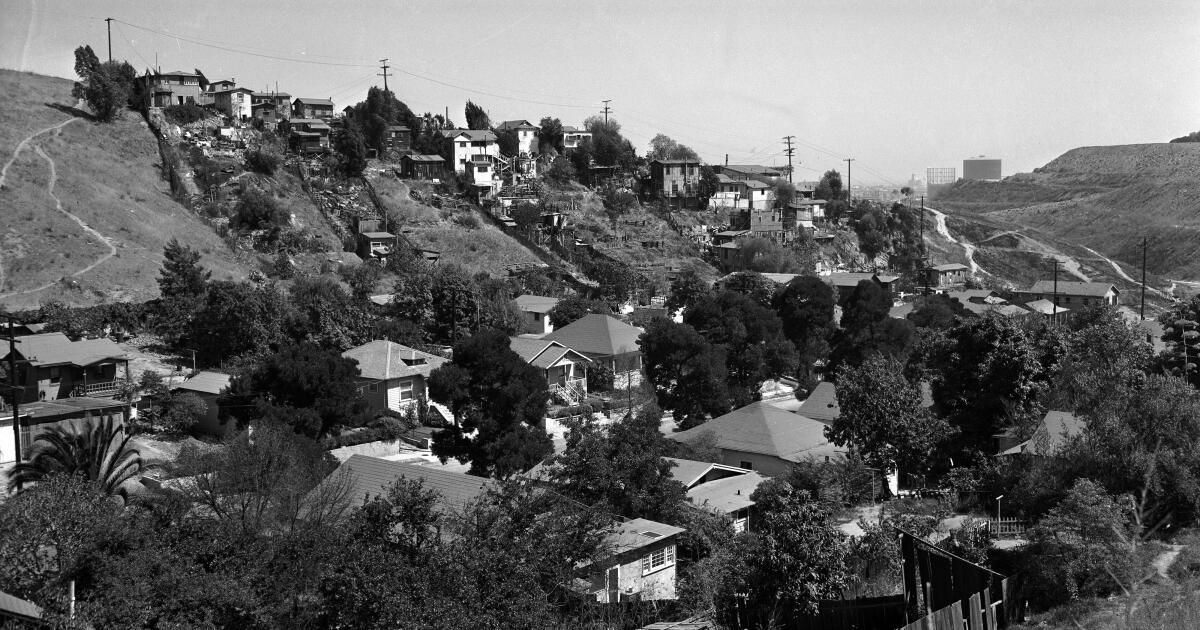

Instead, let's include the stories of these people in our history books. My community was destroyed because the city said we were a poor neighborhood. We were not slums. There was plumbing in the neighborhoods. Many of the Mexican and Mexican American families were third generation and on an upward trajectory. My uncle was a pharmacist and graduated from USC.

Let's put a face to this history and teach future generations not to repeat the city's mistakes.

The city should create a monument in Elysian Park to honor our ancestors who settled Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop in the early 20th century, as required by AB 1950. The city should accept responsibility for unfairly displacing us. This could be accomplished without state legislation that would spend money on yet another commission.

Carol Jacques, Los Angeles

..

To the editor: I would like to remind Angelenos of another missing neighborhood that was taken under eminent domain at the same time Chavez Ravine residents were losing their property. For similar reasons, what happened to Chavez Ravine happened in Bunker Hill, where I once lived.

Bunker Hill, now part of downtown Los Angeles, was made up of low-income residents, powerless, devalued, and in possession of property coveted by a city bent on appropriating it. They, too, were displaced with the promise that they would soon be able to return to new homes. That promise was not fulfilled.

Now I read that there is a “growing movement to get reparations for people whose property was unjustly taken for decades.” While I don't expect compensation, the former residents of Bunker Hill deserve recognition and an apology from the city for what was done to them.

Gordon Pattison, Napa, California.

..

To the editor: What responsibility do the Los Angeles Dodgers and the city have to provide reparations to the people who lived in Chavez Ravine? None.

Many adults who lived in Chavez Ravine are no longer alive. Most families came under eminent domain in 1951. Between 1951 and 1959, Chavez Ravine was primarily open space. In 1959, the remaining families were evicted from land they no longer owned.

The city should not spend millions of dollars on a commission, collecting data on descendants' land ownership and providing tax-free compensation.

AB 1950 presents a “daunting” task. Who determines who gets what? How much will the city pay to defend itself against lawsuits filed by attorneys for descendants who believe they were denied improper compensation?

Although my family left Chavez Ravine in 1951, it flourished elsewhere. Self-sufficiency is a good thing.

Larry Herrera, San Juan Capistrano