Picture this: You're looking to buy a place to live and you have two options.

Option A is a beautiful home in California near good schools and job opportunities. But it costs almost a million dollars. The median California home sells for $906,500. – and you would be paying a mortgage that is increased 82% since January 2020.

Option B is a similar home in Texas, where the median home costs less than half: only $353,700. The trick? Option B is located in an area with significant risk of hurricanes and flooding.

This is not just a hypothetical scenario. It's the impossible choice millions of Americans face every day as America's housing crisis collides with climate change. And we are not handling it well.

Migratory patterns are marked. Take California as an example, which lost 239,575 residents in 2024, the largest emigration of any state. High housing costs are the main driver: The median home price in California is more than double the national average.

Where are these displaced residents going? Many go to Southern and Western Statesincluding Florida and Texas. Texas, that's the top destination for former California residentsmade a net profit of 85,267 people in 2024largely from internal migration.

This is a housing affordability crisis underway. The annual household income needed to qualify for a mortgage on a mid-level home in California was about $237,000 in June 2025, according to a recent analysis: more than double the state median family income.

More than 21 million renter households nationwide spent more than 30% of their income on housing costs in 2023. according to the US Census Bureau.. For them and others struggling to get by, the financial calculations are simple, even if the risk calculation is not.

In essence, the United States is creating a system in which your income determines your exposure to climate disasters. When housing becomes unaffordable in safer areas, the only available and affordable property is often in riskier locations: low-lying areas at risk of flooding in Houston and the Texas coast, or areas at higher risk of wildfires as California cities expand into fire-prone hills and canyons.

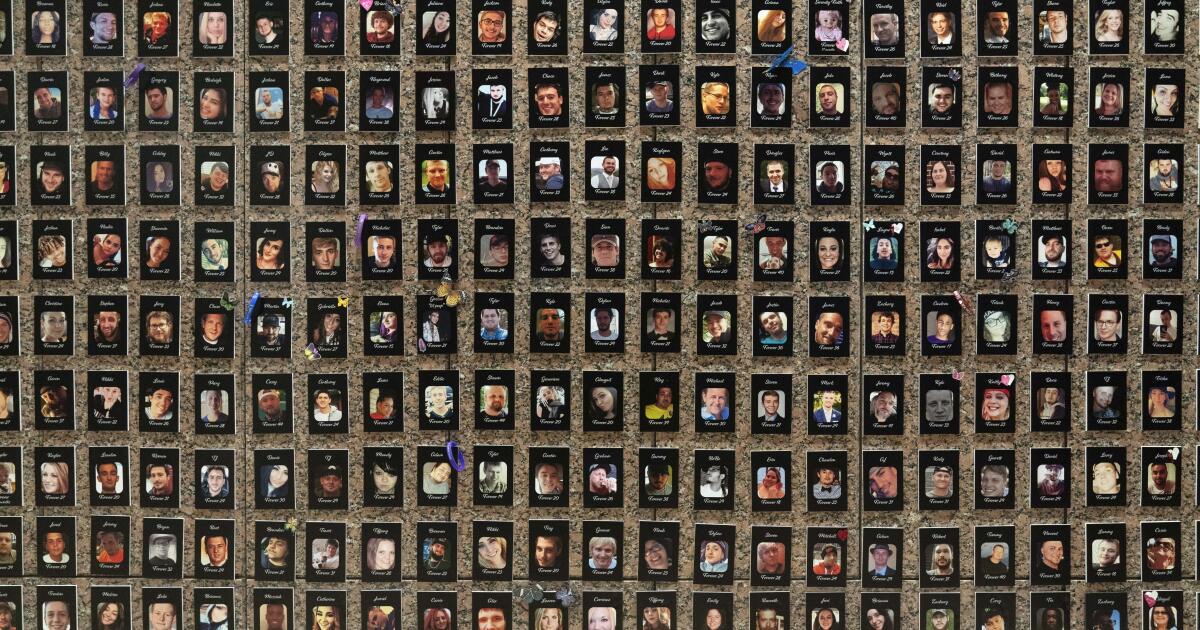

The destinations that attract newcomers are not exactly paradises. Research shows that high-fire risk counties in the United States suffered In 2023, 63,365 more people will enter than leavemuch of that flows into Texas. Meanwhile, my own research and other post-disaster recovery studies have shown how the most vulnerable communities (low-income residents, people of color, renters) face the greatest barriers to rebuilding after a disaster.

Consider the insurance crisis brewing in these destination states. Dozens of insurers in Florida, Louisiana, Texas and beyond have collapsed in recent yearsunable to sustain the growing claims arising from increasingly frequent and serious disasters, such as forest fires and hurricanes. Economists Benjamin Keys and Philip Mulder, who study the impacts of climate change on the real estate sector, describe insurance markets in some high-risk areas as “broken.” Between 2018 and 2023, insurers canceled nearly 2 million homeowners policies nationwide, four times the historically typical rate.

However, people continue to move towards risk areas. For example, recent research shows that people have been moving towards areas with higher risk of forest fireseven holding wealth and other factors constant. The wild beauty of fire-prone areas may be part of the appeal, but so is the availability and cost of housing.

In my opinion, this is not really an individual choice, but a political failure. The state of California aims to build 2.5 million new homes by 2030, which would mean require adding more than 350,000 units annually. However, in 2024, the state added only about 100,000… far below what is needed. When local governments restrict housing development through exclusionary zoning, they are effectively excluding working families and pushing them toward risk.

My disaster recovery research has consistently shown how housing policies intersect with climate vulnerability. Communities with limited housing options before disasters become even more limited afterward. People cannot “choose” resilience if there are resilient places will not allow them to build affordable housing.

The federal government began to recognize this connection, to some extent. For example, in 2023, the Federal Emergency Management Agency encouraged communities to consider “Social vulnerability” in disaster planningplus things like geographic risk. Social vulnerability refers to socioeconomic factors such as poverty, lack of transportation or language barriers that make it difficult for communities to cope with disasters.

However, the agency more recently took a step back on that measure: just as the 2025 hurricane season began.

When a society forces people to choose between paying for housing and staying safe, that society has failed. Housing should be a right, not a risk calculation.

But until decision-makers address the underlying policies that create housing shortages in safe areas and fail to protect people in vulnerable areas, climate change will continue to reshape who will live where and who will be left behind when the next disaster strikes.

Ivis García is an associate professor of landscape architecture and urban planning at Texas A&M. This article was prepared in collaboration with the conversation.