Book review

A sunny place for gloomy people

By Mariana Enriquez. Translated by Megan McDowell

Hogarth: 272 pages, $26

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Critics have called Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez the queen of terror, and since the publication of her magnificent, monstrous novel Our Part of the Night, her fans have turned her into a literary rock star. Her new collection of short stories, A Sunny Place for Dark People, offers another surprising interpretation.

Told primarily in the first person by female narrators, these 12 stories are set in Argentina, with a foray abroad in Los Angeles. While Enríquez revisits themes from her previous work — sexism, illness, and the cruelties of class inequality — the razor-sharp focus on mental, physical, and economic ruin in this collection, which was originally published in Spanish in March, has a distinctly post-pandemic quality. Perhaps the past few years have brought reality more in line with the horror genre. Entertaining, political, and exquisitely gruesome, these stories invoke terror in the context of everyday horrors.

Enriquez has described his sensitivity as twisted — twisted. It draws inspiration from a broad spectrum of influences, including viral videos, Tupi-Guarani myths, popular roadside saints, urban legends, and the Argentine dictatorship of the 1970s and 1980s.

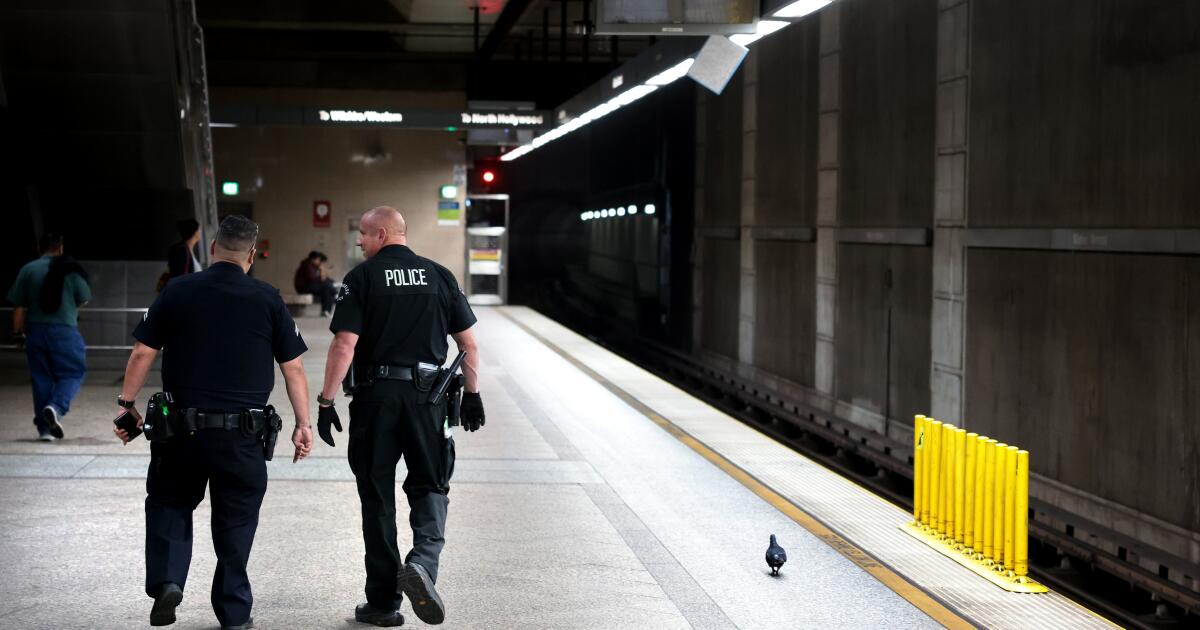

The eponymous story takes place in post-pandemic Los Angeles. An Argentine journalist travels to the infamous Cecil Hotel to observe a ritual. Participants believe they can summon the spirit of Elisa Lam, who in real life disappeared in early 2013; her body was found in a water tank at the hotel a few weeks later. During the investigation, police released a security video showing Lam behaving unusually in the hotel elevator. The video went viral.

“It’s legendary, an Internet classic,” says the story’s narrator. She’s raw, as irredeemable as any of the millions of us who watched the video out of morbid curiosity. Enriquez, a cultural journalist, has a lot to say about the nature of fandom; in a recent work of nonfiction she recounts her obsession with the British band Suede. Here, she illustrates the macabre fandom that arises around a shocking and inexplicable tragedy. The ritual succeeds in summoning something In the water tank. An “answer” comes from beyond the veil, but is that what we wanted?

Readers cannot turn to Enríquez for closure. The retired doctor in “Mis tristes muertos” helps calm and chase away the ghosts of her neighborhood, but they always come back: “It’s as if they were forgotten and we had to start over.”

This is Enríquez’s labyrinth. There are no exits. In “The Face of Misfortune,” a woman tries to break a multigenerational family curse that began with a rape. She believes that telling her daughter, bringing the truth to light, will dispel it. As the curse erases her facial features, she runs blindly toward her daughter and a tremendous fear invades her, since “she did not know if telling her daughter everything was going to be the end or just another mocking laugh… just another trick like the feet whose footprints always led somewhere else, far from their owner.”

“A Sunny Place for Dark People” lacks the deeply imagined lore of Enriquez’s 600-page novel “Our Share of the Night,” which centers on a power-hungry cult and its worship of an all-consuming darkness. But Enriquez still manages to imbue these stories with a sense of place, politics and history. “Hyena Hymns” takes us to a haunted mansion once used as a torture center by the Argentine dictatorship. In “A Local Artist,” tourists visit a ghost town whose abandoned women have been saved by a strange “baby.” “The Refrigerator Graveyard” is set in an abandoned factory that the military used to store weapons and became the site of one woman’s heinous crime.

Feminism and homosexuality are central to Enríquez’s work. In “Metamorphosis,” a woman undergoes a hysterectomy and has several fibroids removed. She decides to keep one, described as “a pale pink, vein-irrigated egg of flesh,” “a hormonal ginger root,” and “a fat mandrake.” It’s not a baby, she insists, but she created it nonetheless. Why let the hospital throw it away? She decides to reinsert it through a unique body modification. The reunion with her fibroid, an experience she describes as “very gentle and very clean,” is more healing than her traumatic hysterectomy. In the world of this collection, it’s a happy ending.

Enriquez’s writing, translated by Megan McDowell, is mesmerizing. I couldn’t look away from some of the tactile descriptions, like “her nails were eaten away as if she had termites under her cuticles.” The humor is dark: “the tantrum of a woman who has just had a hysterectomy” (a pun on “hysteria”). Her images are often sickening, perfect. In one story, a milk container rolls down the front steps of a house and explodes pink, a symbol of the gruesome double homicide that has occurred inside.

In their morbid tapestry, these stories also invoke other writers, music, fashion and the arts. The collection includes epigraphs by Thomas Ligotti and Cormac McCarthy; characters reference “Game of Thrones,” a Michael Myers mask from the “Halloween” movies and Taylor Swift. “Night Birds,” which echoes Shirley Jackson, was written for a 2020 exhibition of the work of the Argentine artist Mildred Burton. “Julie,” about a young woman who claims to have sex with ghosts, should be paired with Marjorie Cameron’s 1955 drawing “Peyote Vision,” of a woman having sex with a demon. And “A Local Artist” includes descriptions of paintings so disturbing I longed to see them.

Enríquez has numerous works that remain untranslated from Spanish, including novels, novellas, and a nonfiction exploration of cemeteries. “A Sunny Place for Dark People” is another argument for bringing more of that work to a wider audience. If we look for justice, redemption, and freedom in Enríquez’s stories, we will be devastated; her characters are lucky to survive. But we are lucky to witness their strange and fascinating journeys.

Gina Isabel Rodríguez is a fiction writer and essayist. The daughter of Chilean immigrants, she is revising a novel set during the Pinochet dictatorship.