Objectively, this is an astonishing progression in a short period of time. In 2008, Barack Obama, a Democrat, became the country's first black president. Sixteen years later, Kamala Harris is on the verge of becoming the first black woman chosen by the party as a presidential candidate.

But a lot has changed in 16 years.

The defining meaning of Obama’s historic candidacy, his brand, was hope. The simple symbolism of a black man in the White House made millions of us think differently about ourselves. Harris’s rise is no such symbol. She becomes the Democratic nominee because, as vice president, she was handed the baton by an aging white man who was forced to step aside because of concerns about his ability to do the job.

In other words, Harris’s skin color is not as important as her ability to do that job — not just to take President Biden’s place on the ticket, but to get Democrats across the finish line. She must salvage the desperate, dwindling hope that the entire nation can regain its moral footing in the face of the onslaught of MAGA recklessness and complacency that is eroding America’s shaky democratic foundations.

This is a much bigger task than Obama had to face. During his candidacy, the country also faced a crisis, the housing collapse that led to the Great Recession. That certainly tipped the scales in Obama’s favor, though the hope that was at the heart of his campaign remained strong. When he won, the joy and optimism that erupted across the country was due to the triumph of the “better angels,” not the idea of “it’s the economy, stupid.”

What Harris faces is an existential crisis that may paralyze as much as it motivates. This election is not born of joy or hope, but of a troubling question: Can we ever again assume that those in charge (not just Democrats) will be people of good will? There is growing cynicism that Republican chicanery, from voter suppression laws to a motley Supreme Court granting Trump criminal immunity, will continue to crop up, regardless of the outcome of the vote. The election simply won’t matter.

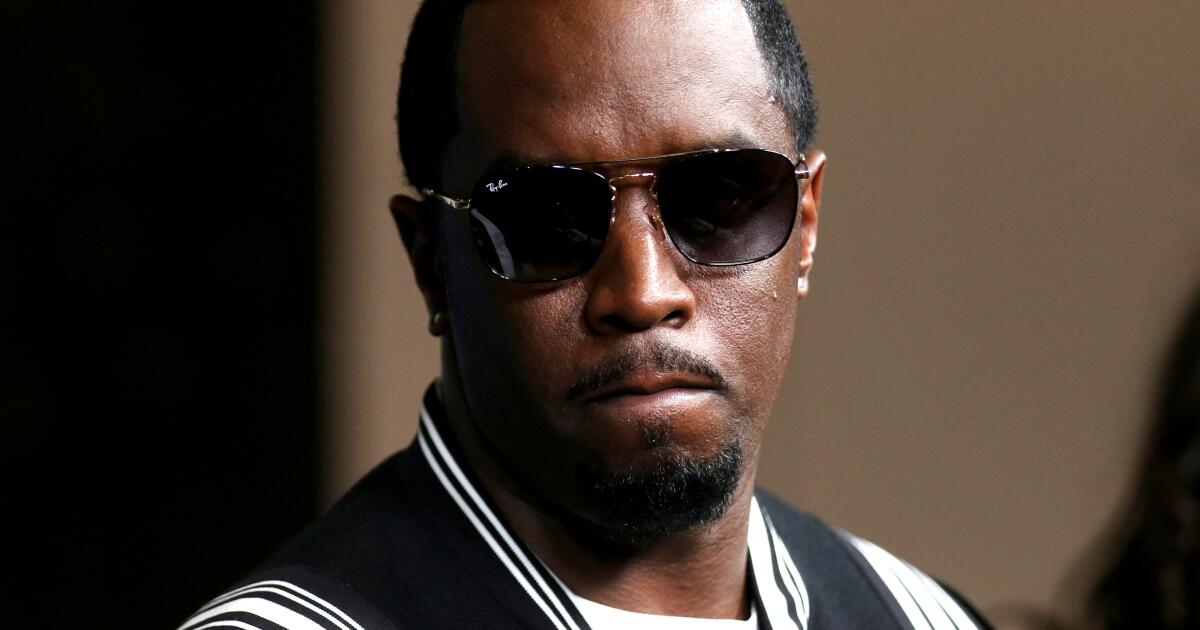

Harris appears well prepared for this tense moment. She wants to fight. Trump has made fighting a central element of his campaign, especially after the assassination attempt, though MAGA has always been belligerent, direct and dismissive of “wokeism.” Harris, a former prosecutor, is already in battle mode. She knows Trump’s type, as she has been telling rally-goers, because he stood up to predators, grifters and abusers. She is offering what Democrats desperately needed: an avatar not of hope, but of nagging.

Harris seems to relish the prospect. All her past mistakes and public struggles to convey a core ideology — as vice president and before that in her failed 2020 presidential campaign — can be forgiven if she leads with an obligation to fight back.

The fact that it was a Black woman who responded would be all the more satisfying. Trump is a racist who despises Black women, especially those who have dared to criticize him or hold him accountable: Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, federal judge Tanya Chutkan, U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters. Harris would have a platform like no other. As a presidential candidate, she would be on equal footing with Trump, her counterpart. And as a Black woman, she could skillfully carry the legitimate anger of so many Americans — women, gay and trans people, poor people, and immigrants — all of whom find themselves caught in the MAGA crosshairs.

For all the grimness and stakes at the moment, there is an undeniable magic. Harris had a gilded career in California, rising from San Francisco district attorney to state attorney general and then U.S. senator with relative ease. She called herself a progressive, and while critics have not embraced that, especially for her actions as a prosecutor, she is, at the very least, a solid Democrat. Her 2020 primary campaign stalled her ambition only briefly; Biden chose her as his running mate, the first Black and South Asian woman to be on a major party’s presidential ticket. Having broken that barrier, she is set to break another in a sudden twist of fate.

All of that drama excites certain segments of the party, especially Black women, a key constituency that must turn out to vote for Democrats to have any chance of winning in November. The “Black women’s phone call” that took place just after Biden’s withdrawal announcement catalyzed an unprecedented surge of financial support for Harris. The Zoom meeting, organized by the organization Win with Black Women, raised $1 million in an hour, evoking the infectious racial pride of Obama’s first campaign. A friend of mine who was on the call, which came to include thousands more women than expected, described it as “really something to behold.”

I have no doubt that was the case. But I cannot forget that Harris is rapidly being embraced not so much for who and what she is, but for who and what she is not: Trump, and in a different way and for different reasons, Biden. She is likely to be the Democratic nominee who will become a lifeline for all of us, for progress itself, and if being of color makes her a better lifeline, that is a plus. But of course we don’t know if she will be. What hasn’t changed in the last 16 years, what has only gotten uglier, is that racial and gender gap.

There are many attacks coming. Whether we can defeat them depends less on Harris than on the “we,” which is the true foundation of democracy.

Erin Aubry Kaplan is a contributing writer for Opinion and a columnist at Capital and principal.