Book Review

The Power of Chinatown: Seeking Spatial Justice in Los Angeles

By Laureen D. Hom

UC Press: $29.95, 300 pages

If you buy books linked to on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Laureen D. Hom, author of the new book “The Power of Chinatown: Searching for Spatial Justice in Los Angeles,” admits that she had originally “dismissed Chinatown as too personal” and wanted to “move on,” like so many others. She is Chinese Americans of her generation, solidifying her thesis plans as a doctoral candidate in urban planning and public policy at UC Irvine. However, the death of both of her grandmothers while she was in graduate school forced Hom to consider what Chinatown meant to her family, now that the first-generation elders who had lived there had passed away.

Hom took on Chinatown as an intellectual project, engaging in rigorous research and field work on the history of development, political power, and the intimate human stories of the neighborhood's legacy in Los Angeles. The result is a rich community history that illuminates the heterogeneity of Chinese American (and, more broadly, Asian) racial politics in forging the evolving and continually contested identity of an urban ethnic space, and a call to action to Let Asian Americans envision a just society and equitable Chinatown for the next generation.

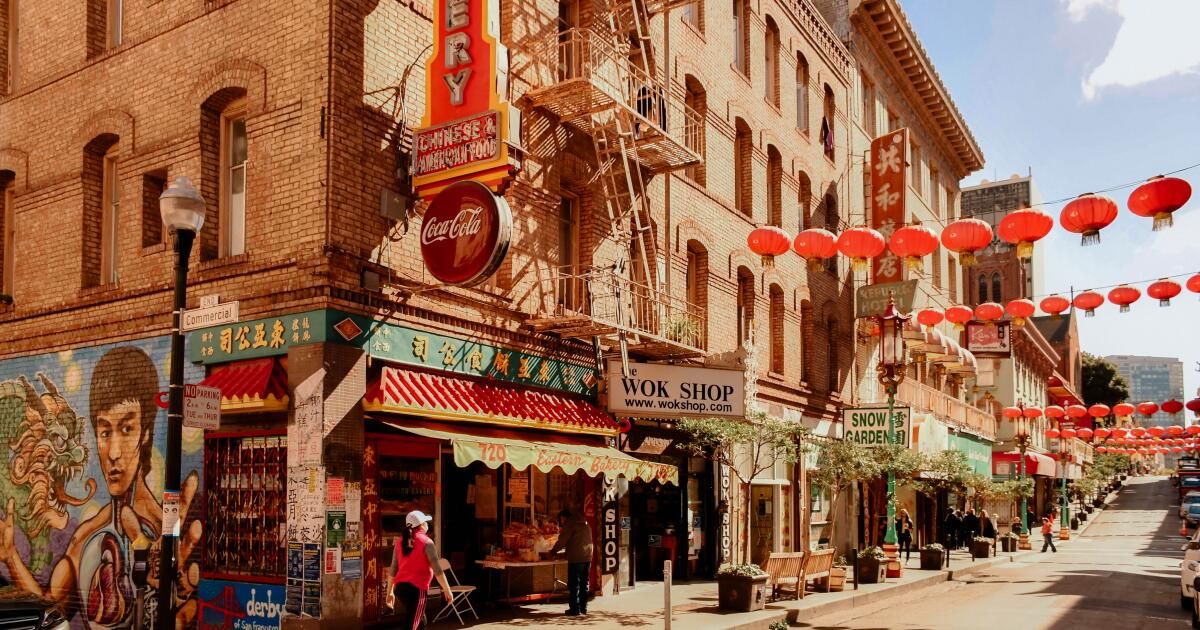

Hom's research interests in gentrification and civic engagement in Asian American communities took her in 2012 to Irvine, where Asian Americans had been settlement in newer, often suburban areas, rather than in historic urban ethnic spaces like San Francisco's Chinatown, where Hom grew up.

That same year, however, Hom's interest was sparked by the controversial development proposal for a Walmart neighborhood market in Los Angeles' Chinatown. Residents, business owners and grassroots organizers had starkly different ideas about whether a Walmart best served community.

Chinatown in San Francisco, where author Laureen D. Hom grew up.

(Christopher Reynolds/Los Angeles Times)

The Walmart opened in 2013 and closed three years later. Community leaders argued it would bring resources to predominantly low-income residents. Progressive activists, however, pointed to Walmart's history of labor violations and its potential to drive small businesses out of Chinatown. The controversy also raised questions about who has a say in controlling preservation and change. What role did members of the geographically dispersed Chinese-American community in greater Los Angeles, like Hom, play in shaping the future of Chinatown?

Hom wanted to know more: He embarked on an ethnography of political culture in Los Angeles' Chinatown as it relates to gentrification, community development, and cultural preservation. Hom's fieldwork between 2014 and 2018 includes interviews with 52 community leaders. She also attended and participated in more than 90 community events and public meetings, and conducted meticulous archival research on the history of the neighborhood's development.

Historic Chinatowns across the United States face the pressures of gentrification, contributing to the belief that these legacy neighborhoods are disappearing and will soon disappear from the American urban landscape. Hom argues against this narrative, stating that ethnic enclaves are sites where “the identities of racial communities are reproduced, contested, and rearticulated” and therefore the political processes that contribute to and respond to gentrification are also a project. critical race. Conflicts over gentrification in the community, Hom argues, are a critical intersection of “how we define community, the commodification of land, and the impacts of racialization of our communities.” Hom's intervention as an urban theorist adds powerful perspective to existing social and political case studies of Los Angeles' Chinatown as a singular expression of race, class, and culture.

At the end of the 19th century, Asian immigrants were perceived as unassimilable “others” and were legally denied citizenship. Since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 eliminated quotas that favored EuropeansThe racialized identity of Asian Americans has largely become the image of the “model minority”: educated, upwardly mobile, white-adjacent.

Hom theorizes that certain elites in Los Angeles' Chinatown have directed development to support this simplified representation of Chinese Americans, including those with business interests in the neighborhood who have fabricated a narrative of the community's transition from a ghetto. ethnic group formed from racial exclusion into a vibrant enclave. with emerging socioeconomic power. However, Hom also highlights the progressive Asian American antigenrification organizers in Los Angeles' Chinatown, whose civic engagement emerged from the anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist philosophies of the 1960s.

Hom begins with a history of Los Angeles' Chinatown through an urban planning lens, providing readers with a racialized political context for contemporary development issues. Hom traces the trajectory of neighborhood development, informed by the intersection of immigration and urban development policies. Throughout the book, Hom shares excerpts from interviews with community members; It is a pleasure to “hear” directly from these voices, as Hom skillfully weaves a series of dissenting narratives into a fascinating vision of a diverse community.

An acronym-filled chapter studies the variety of community organizations that have historically provided space for public participation in discussions about neighborhood development. Hom's survey offers readers a poignant insight into the internal tensions that arise with local community work. Another chapter is dedicated to how community leaders eschew the term “gentrification” for “balance” in Chinatown. Although, of course, there is a dispute over the “right” balance, such as maintaining affordable housing and luxury amenities in new residential developments and creating new businesses that attract tourists without threatening the legacy institutions that serve the community's working-class residents. . Going forward, it offers a multi-layered picture of how the neighborhood's built environment (businesses like galleries and restaurants, and public cultural events) contribute to cultural displacement. This fascinating chapter interrogates the problem of defining ethnic culture amid a lack of political tools to protect and preserve the neighborhood, as Hom returns once again to the question of who has the right to promote and control change in Chinatown.

“The Power of Chinatown” lucidly examines why historic urban Chinatowns still matter: place-based racial politics are continually reshaping neighborhoods' physical environments, amid gentrification and forced displacement. Hom effectively argues that Chinatowns persist and change simultaneously; They are static sites with radical potential for equitable development, if countless Chinese and Asian American actors across generations, socioeconomic status, and immigration cohorts commit to a vision of spatial justice that foregrounds histories of resistance. and collective power.

Jean Chen Ho is the author of “Fiona and Jane” and an assistant professor of creative writing at Chapman University.