Refusal is a powerful political act. Acting in defense of themselves, Black people and Black women in particular have systematically rejected the terms of oppression, discrimination, and dehumanization. Rejection is a forceful no, full of energy and meaning. “We refuse” is similar to black colloquialisms like “nah,” “no,” “not today, Satan,” or my personal favorite, “Oh hell no.”

The resistance is as one responds to white supremacy; the refusal is the reason. In the United States, we tend to focus more on how resistance is manifested or performed. Not enough emphasis is placed on why the resistance is so crucial to American history.

My great-grandmother Arnesta helps tell that story. In 1915, Arnesta was 9 years old in rural Alabama when she stepped on a rusty nail. Shortly after, the infection appeared and Arnesta became seriously ill. She most likely suffered from tetanus, which can be fatal if left untreated. Her mother, Mary, was frantic.

Mary took Arnesta to the only doctor she knew, a white man who lived in a large house on the other side of town. The doctor agreed to help Arnesta, but with one condition: that after curing her, she would have to live in her house and work for her family for the rest of her life. Slavery had been abolished 50 years earlier, but the doctor felt entitled to Arnesta's life and work in perpetuity.

For a black girl living during one of the worst periods of race relations in the United States, these were detestable but sadly predictable terms of compromise. The deal the doctor offered included a life of servitude and perhaps worse—a far cry from the doctor's oath to “first do no harm.” Maria was in a panic. Since she did not want to lose her daughter and her only son, she accepted.

Fortunately, my great-great-grandmother, who was previously enslaved, intervened. She rejected the doctor's excessive offer, picked up her sick granddaughter and took her home. There she administered all the natural remedies available to her. Arnesta survived, but for the rest of her life she walked with a limp. For me, this story has always summed up the power of white supremacy: choose a life of slavery or refuse and limp. What has formed me is not the doctor's proposal but the refusal of my ancestor. His answer was not no, but never, an answer that denied his authority to white supremacy.

Refusal sets boundaries and has defined unacceptable human interactions as those that deny dignity, respect, and decency. It is not apathy or cynicism, but an insistence on a fully lived human experience. It is not giving up the vote or looking at the world. Refusal requires activism through traditional or creative methods, of the kind recognized and celebrated by LGBTQ+ communities in June, Pride Month, and by African Americans on Juneteenth, to defend freedom for all.

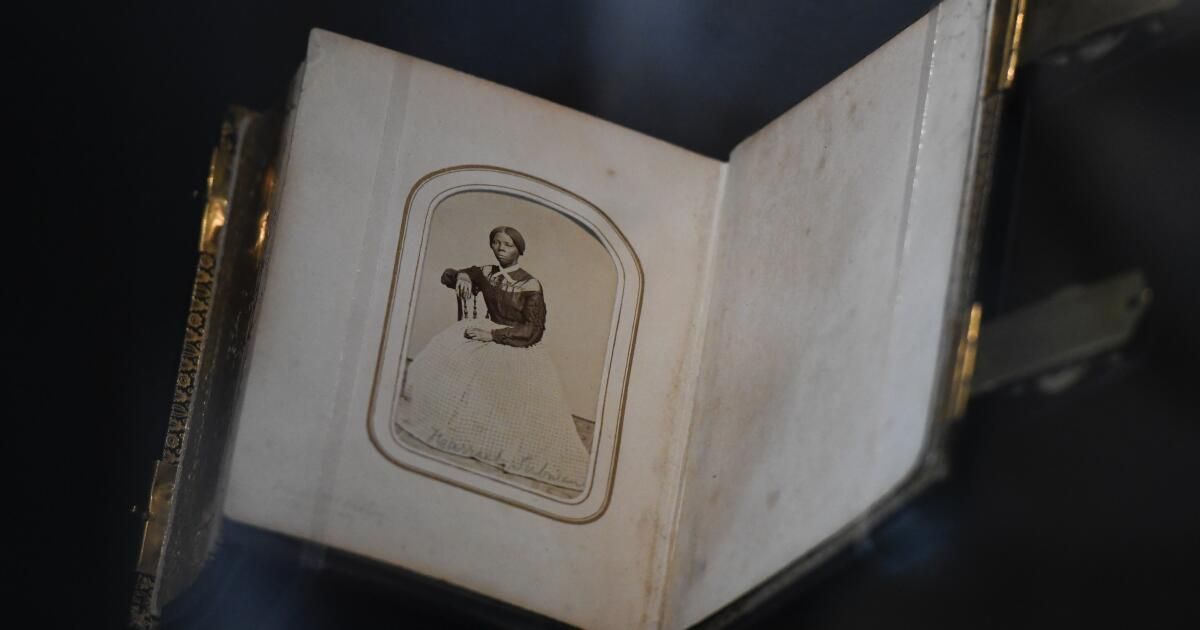

This activism has created countless programs that fed, educated, healed, and cared for Black communities. Many critical steps in ending slavery were acts of refusal: the Underground Railroad was created because abolitionists refused to be complicit in oppression and abuse. Black leaders and white allies formed protective societies and published newspapers, pamphlets, and personal narratives to establish a national abolitionist agenda based on intellectual, rhetorical, political, and physical rejection. When some 250,000 black soldiers fought during the Civil War, they rejected slavery on American soil.

In a similar spirit, during the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther Party rejected second-class citizenship, creating national breakfast programs, health clinics, ambulance services, legal aid, schools, and care programs to reject the void. of public services available to blacks. American people. In a period of racial and political unrest, the Black Power movement focused on joy and solidarity, invoking hope, happiness, and kinship as a shield against the demoralizing and degenerative effects of racism. James Brown’s “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” was a refusal to allow white supremacy to determine what is beautiful, inspiring, or good.

Although it can be carried out by an individual, at its core, rejection is collective. That is why the sentiment behind the phrase “we refuse” persists among subjugated people. It has been a key refrain in Black and Native American feminist politics, reiterating that oppressed people can and must refuse to be invisible, silenced, or denied. From slave ships arriving in the New World, through slavery, segregation and persistent structural racism, black people have always fought back.

And black culture refuses to be defined by oppression. Rejection has been our anthem, a way of being, present in the novelty and genius of our vernacular, in the newspapers and literature we create to tell our stories in the face of attempts to deny us literacy. It is present in the drums, banjo and bass that permeate our music that refuses to be replicated or erased, in the voices that refuse to be timid or diluted. It is even present in our traditions of forgiveness and hospitality in societies that are often unwelcoming to us.

The revolutionary culture, art, and community that have emerged from these traditions are proof that, like my ancestors, we can forge a new path and reject the choice between a life in bondage or limping. Now and always we can refuse and insist on creating our own destinies.

Kellie Carter Jackson is professor of Africana studies at Wellesley College and author of “We Refuse: A Strong History of Black Resistance,” from which this piece is adapted. On X/Twitter: @kcarterjackson