Next week, the world's largest history organization will host a briefing on Capitol Hill in Washington to share its findings from a two-year study that looked at, among other areas, the teaching methods of the nation's educators.

It's not going to be pretty.

Opinion columnist

Granderson Landing Station

LZ Granderson writes about culture, politics, sports, and navigating life in America.

The American Historical Association calls the report “the most comprehensive study of secondary history education in the United States undertaken in the 21st century.” It identifies the events of 2020 as the impetus for this review, calling it a year of “contentious debate over history education” that has “generated outrage, outlandish claims, and a growing sense of alarm in homes and communities across the country.”

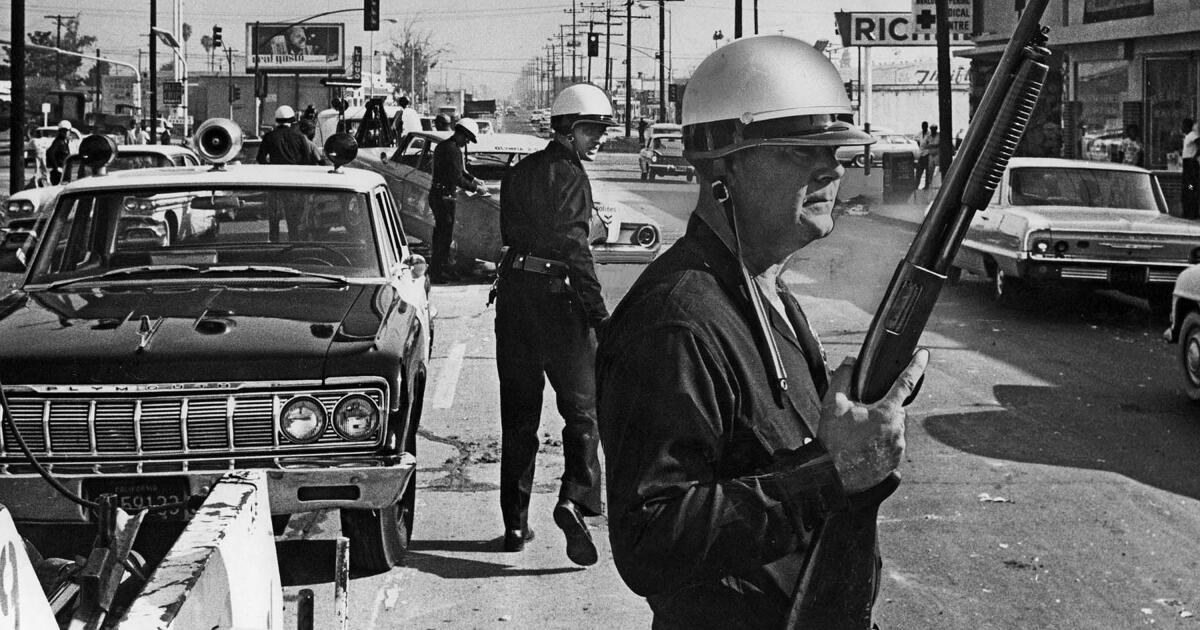

The pandemic that struck in early 2020 was devastating, and the presidential election in late 2020 was consequential, to say the least. But history may well show that the events of that year that most transformed America were the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery.

Much of the country didn’t even know anything about Juneteenth or the Tulsa massacre until the protests sparked by these three murders forced this nation to have deeper conversations about race relations and our past. Collective ignorance has held us back. The reason we can’t have a serious conversation about reparations is that too many Americans don’t know the history of this country. The real history. Not the history that fed Baby Boomers stories about “Christopher Columbus discovering America” or George Washington who “can’t tell a lie.”

From legislative backlash against the 1619 Project to the conservative effort to downplay slavery as a cause of the Civil War, history lessons have too often been edited to protect white comfort, to the detriment of this nation’s progress. In many ways, that’s why we still talk so much about race. It’s not that racism will never die; it’s that we have a knack for keeping lies alive, which means the fight for candor has to continue, too.

Of course, there are those who prefer lies. They romanticize past moments in America as “the good old days” — hence the “again” emblazoned on those red baseball caps. To them, it’s all a game and history is written by the winners. But we’re all in this together. They can’t see the flaw in cheering on their own teammates. Some on the right are so committed to their fantasies about America’s past that the truth seems like a betrayal.

Hopefully, the historical association’s study — “Mapping the Landscape of Secondary US History Education” — and the subsequent briefing in Congress will be an important step in helping elected officials and educators identify how to change this limiting way of thinking.

All 50 states were represented through a legislative review, over 200 interviews with teachers and administrators, and the 3,000 surveys of middle and high school teachers reviewed. It's refreshing to see experts weighing in with data, rather than the flood of unsubstantiated book posters using (likely unsubstantiated) anecdotes to scare school boards.

The American Historical Association is a nonpartisan organization, so there is a glimmer of hope that its work will not be dismissed by conservatives who disagree with the results. If the country can find a way to bridge the gap in thinking about how to teach history, then perhaps the generations that inherit this land will not be burdened by our ignorance, willful or otherwise.

Earlier this week, during her interview with members of the National Association of Black Journalists, Vice President Kamala Harris was asked about reparations for the descendants of slaves and whether she would create a commission to study it or support one in Congress. Her friend, the late Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, advocated for the latter for decades, noting that the call for reparations for slaves came after the 1987 Civil Liberties Act provided reparations to Japanese Americans affected by World War II prisoner camps.

“We need to tell the truth about the generational impact of our history,” she said. “And we need to tell the truth about it in a way that will help drive solutions.”

Generally, that is not what is happening. Consider this: Depending on the format, Plato’s “Republic” is usually around 400 pages long. Written around 380 BC, the text has survived many global calamities, but it cannot overcome the fact that it is boring, at least by today’s standards. Of course, “The Republic” was never intended to be a light book, and it surely exceeded all initial expectations by becoming so important to Western philosophy and the formation of governments over the course of more than 2,000 years.

So imagine my surprise when I saw it among the titles offered by a book summary app that promised that the ideas in “The Republic” could be all mine in 15 minutes or less. I used to listen to a chapter of an audiobook while walking the dogs. Now, I can “read” Plato’s masterpiece in two poop bags or less. I imagine that by the end of the year, I could “read” half of the Los Angeles Central Library if I didn’t care about details like detail or context. If I didn’t care about learning.

Aside from the culture wars, and perhaps in part because of them, this is what has happened to history in general: it has been boiled down into bullet points so that we can grasp the essence. It's like cramming for a test instead of learning the material. That's why when race relations in America are put to the test, we continue to fail.

@LZGranderson