The death of a parent is often a heartbreaking and disconcerting experience for adults. For a child, it is even worse, fuelling feelings of frustration and abandonment and sometimes self-destructive behaviours, such as drug use, that can continue well into adulthood. This has particularly severe consequences when the child is black and therefore more likely to end up in the child welfare system.

A recent report A study by federal researchers provides the most comprehensive picture yet of the widespread impact of overdose deaths on Black children in Los Angeles and other cities — and what we can do about it.

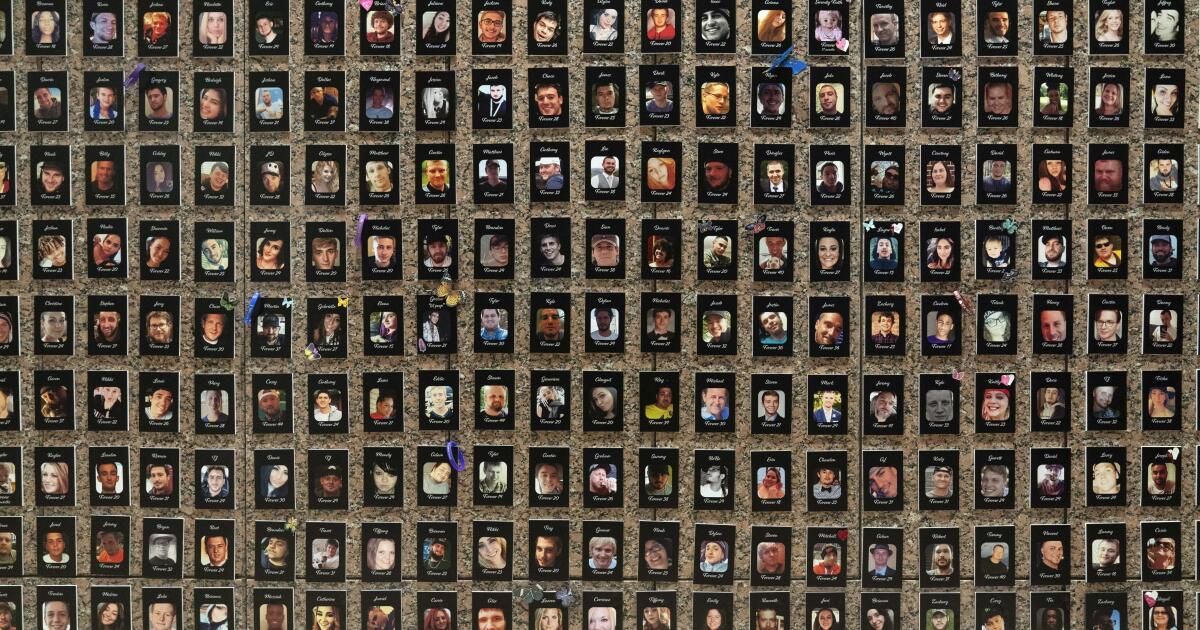

From 2011 to 2021According to the report, more than 321,000 American children have lost a parent to a drug overdose. Black children experienced the largest increases in the rate of such losses during those years, aggravated A long-standing public health crisis across Black AmericaLike much of the United States, Los Angeles has seen a rise in drug overdoses in recent years, with Disproportionate losses among black adults in the city.

Black people are significantly more likely to suffer drug-related deaths Because of limited access to treatments and resources like naloxone, which can reverse overdoses, when parents are involved, the toll on their children is swift and profound. Parental drug use is highly associated with drug use among children.

Although black children make up only 7.4% of the population in Los Angeles CountyThey represented 24% of those who entered the child welfare system in a recent year. A study found that approximately 47% of black children in California were subject to an investigation for maltreatment before age 18, and substance use accounted for 41% of child abuse cases in the state.

The disproportionate number of black children in the Los Angeles child welfare system has been under scrutiny since the late 1980s, the height of the heroin and crack epidemics in Los Angeles. Drugs, then largely addressed as a criminal problem through heavy-handed policy and prosecution, condemned a generation of young and middle-aged black Angelenos, both users and dealers, to premature death and incarceration. Many of their children ended up in the city’s fragmented child welfare system and, all too often, on a similar path to addiction and entanglement with the justice system.

When a parent dies, other family members — the other parent, grandparents, aunts or uncles — are the first to take on the responsibility of caring for them. But black children, especially those from low-income communities, often end up in the child welfare system.

Why? Surviving family members of the child may lack the resources to fill the gap, but racial bias also predisposes child welfare workers to separate black children from their families and hinder reunification efforts.

Research has consistently shown that Child welfare workers more easily define black parents' behavior as abusive or neglectful. Even when it is comparable to the behavior of parents of other races. Child welfare workers are also are more likely to view black families as less loving to their children and less redeemable.

Children who enter the child welfare system due to the death of their parents are already twice as long in the systemBlack children tend to stay in the system even longer because of prejudice.

The ravages of the opioid epidemic in Los Angeles and its child welfare system are daunting, but not irreparable. The first necessity is to reform the city’s racially biased child separation process. Los Angeles officials have been testing a “blind separation” approach in which investigations are followed by a decision-making process that excludes demographic details such as the child’s race. This is a step in the right direction.

However, A UCLA study on the pilot The program revealed that racial disproportionality persists, demonstrating how deeply rooted biases are in child welfare. For blind culling to be effective in eliminating racial disparities, it must be complemented by greater transparency, expanded coverage, and increased access to care. civilian review boards and implicit bias training.

Second, we need to better understand the consequences of placing Black children in the child welfare system. In general, Black children in the system are highly stigmatized, especially when they come from families with a history of drug abuse. That contributes to making them more vulnerable. less likely to be adoptedThe trauma of losing a parent also means they are more likely to experience depression and anxiety.

These experiences often lead to social isolation, poor academic outcomes, limited employment prospects, and incarceration. Policymakers must work to identify these patterns early and provide resources, such as mental health care, to interrupt this damaging cascade.

Finally, policymakers should continue to explore the benefits of a guaranteed basic income to provide a cushion for personal and professional growth. Another pilot program in California Provide a guaranteed basic income to those leaving care at age 21 or older.The state should lower the eligibility age to 18 to take into account the significant housing and employment challenges facing young black men as they become adults. Stanford researchers and other institutions have found that such policies lead to better health, housing security, and employment prospects.

Addressing the growing overdose epidemic in Los Angeles’ Black communities requires attention not only to the immediate risks faced by drug users, but also to the childhood experiences that often lead them to use. One of our most powerful tools for preventing future overdoses is to better care for the children most directly affected by today’s losses.

Jerel Ezell is an assistant professor of community health sciences at UC Berkeley who studies the racial politics of substance use.