A fleeting memory from the archives of my life: It’s the summer of 1997, and we’re moving my disabled sister, Wendy, into a nursing home. She’s in her bedroom at my parents’ house. She’s a woman in her 30s who needs 24-hour care, and my elderly parents can no longer provide it. Her life is being dismantled around her: her ornaments are carefully packed away for transport, the cords from her prized stereo are unplugged and set aside in a snake-like tangle. My sister can’t understand what’s happening. She looks up at me from where she’s sitting on the floor and angrily yells, “I’m not going to be able to get my hands on it.”Because, why “Do things have to change?”

This memory has been on my mind for several weeks, ever since the US presidential debate. At first glance, nothing about Wendy reminds us of President Biden's life (he never had the chance to play politics or run a country), but the more I see Biden caught in the gears of time or doing his best not to confront it, the more I realise that he is fighting the same war my sister fought for decades. We are all called to those front lines, where we all, in the end, lose.

Wendy had a brain tumor as a child. The surgery to remove it was fraught with postoperative complications. And yet, she defied many odds, living to the age of 52 and regaining mental and physical faculties that doctors initially said had been forever destroyed. In many ways, she was the beating heart of our family. I always felt that her life told the story of the kind of people we were. She was the person who defied the odds, and we were the ones who never stopped betting on her. It's a good story. A Hollywood story, even.

At some point, stories of “beating the odds” can turn tragic, starting microscopically. The line between hope and delusion grows thinner, and in the moment, it’s sometimes hard to know when you or your family are crossing it. Some people will never walk again. Some brains will never heal. You can’t beat odds that are unequivocal, either. Those aren’t even “odds,” really, because the expected outcome isn’t possible. One of my hardest jobs as a doctor is helping patients and their families face the moment when those odds lead them toward an inevitable truth — one we’re all tempted to resist.

Like my sister, Biden survived a dangerous neurosurgery, in his case After the aneurysms in 1988But what my sister and the US president have most in common is a personal narrative about overcoming adversity, which Biden alluded to in his much-criticized speech. interview with George Stephanopoulos. Biden may be the author of his own narrative of triumph, but in my sister’s case, that story came from the people who loved her. They were both cast in that classic Hollywood role: the fighter who could never be dispensed with, no matter the odds.

Practicing medicine has helped me stay grounded when it comes to the notion of “fighters.” While personal characteristics such as resilience are important, they cannot overcome the inevitable. Decline and death are non-negotiable parts of life.

And yet there was still There were times when even I believed my sister would overcome any adversity. In those early years, every time she nearly died, she seemed to bounce back. But it was also true that as the years passed, with each new medical challenge, she was like a basketball with a little less air in it. It no longer bounced. Deflated, it slowly began to fade away. Her brain, vulnerable after the surgery and subsequent seizures, had no reserves to absorb further injury. If she had nine lives, then she had suffered enough for nine lives, too. When she died, she was a shell of her former self.

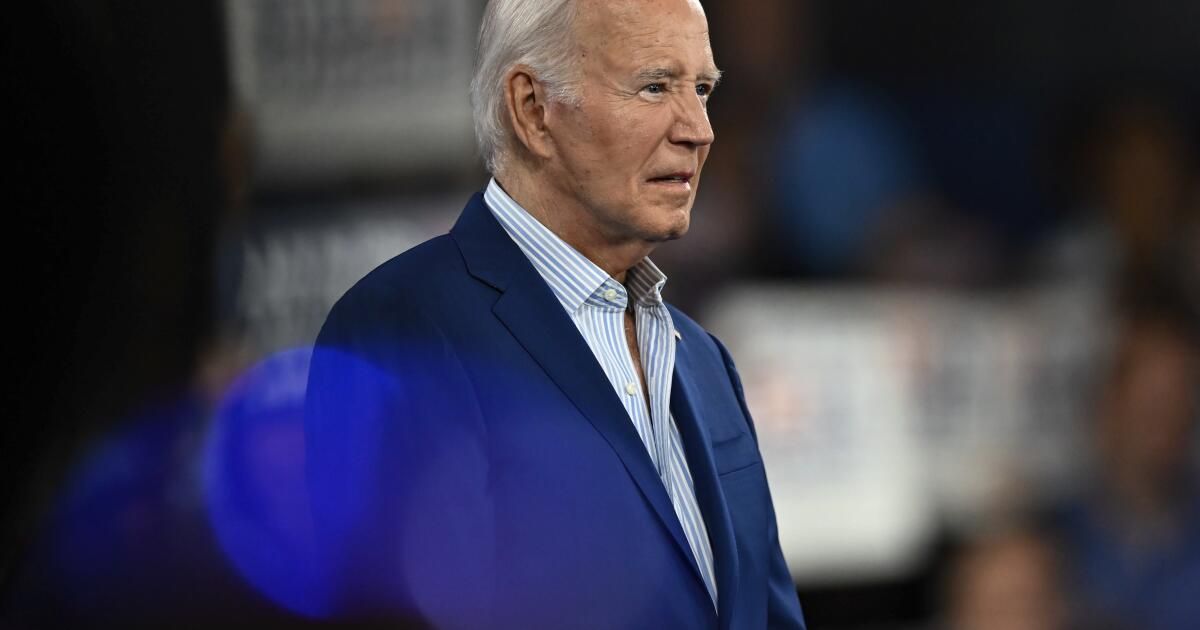

Biden also seems despondent, a shell of the lackluster, inspiring career politician he once was. His apparent lack of understanding of the public’s concern about his health is an alarming symptom in itself. Nothing seems to shake his insistence that he will recover.

The irony, of course, is that Biden’s self-image as a fighter has served him well so far. He bounced back early, smiled, and persevered. His family has likely come to believe in his “fighter” status as some kind of mythical, unassailable truth, and I’m sure that story has given them power and comfort during very difficult times. Don't count Dad out. Other people have made that mistake before.

But “other people” aren’t the only ones capable of making errors in judgment when it comes to our loved ones. Some research A study shows that cognitive decline in older patients can go unnoticed by families unless it is accompanied by behavioral symptoms and signs. Even when someone struggles to perform an act as simple as making toast, our long history of trusting in their powers can blind us to what is happening in real time. Even when not just the toaster but the entire house catches fire, families who have watched their loved one regress time and time again find it hard to believe that they won’t see that same magic trick again, just in time.

Time. Isn't that what it all comes down to? Not so much the right moment as the cuts of time: death by a thousand little cuts. The story of our lives cannot rewrite the story of life. Things have to change. Sometimes we can't understand why, and it hurts. But we can't change the reality of what comes next.

Jillian Horton is a writer and physician. Her first book, “We Are All Perfectly Fine: A Memoir of Love, Medicine and Healing,” is being adapted for television. @jillianhortonmd