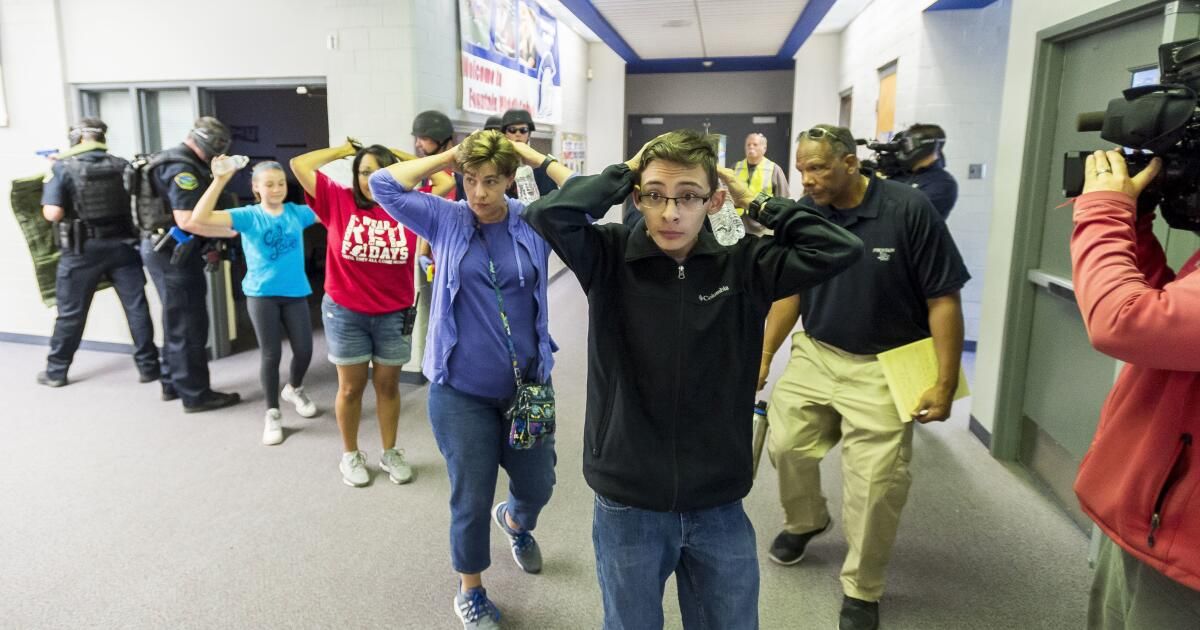

A school safety drill in San Gabriel came to a head last week when, according to parents and students, the elementary school principal walked around, using her fingers to simulate holding and firing a gun. She reportedly pointed to individual students and said, “Boom. You are dead.”

Principal Nina Denson has been removed from her duties while the school district investigates parents' complaints. If the allegations are true, it would appear that Denson was acting on a terribly mistaken belief that traumatizing children is the way to get them to take exercise seriously.

Although the circumstances in this case appear to have crossed a line, it is worth considering whether schools are overdoing disaster drills, especially those involving gun violence. Certainly, drills are needed in some situations: “evacuation drills” for fires and “cover and stay still” for earthquakes. There are also shelter-in-place drills when off-campus circumstances require students to remain in school. “Reverse evacuation drills” have students return to the school building when there is a dangerous situation outside. Then there are lockdowns or active shooter drills.

California schools require disaster drills and other “multi-hazard” drills. But school officials should think more about how many drills are performed and how to reduce the level of fear, especially in young children, because researchers say there is no objective evidence that they increase preparedness for a dangerous attack.

Most schools don't do anything like what allegedly happened at San Gabriel. On the other hand, some exercises have been worse. Without warning that a drill was approaching, a preschooler blasted the sound of gunshots through his speakers. Some Missouri schools had students paint what looked like bleeding bullet holes on themselves. In 2020, San Marino High School was planning a drill in which police would fire blanks for 11 minutes so students would understand the sound of gunshots. The high school backed down after the American Civil Liberties Union raised concerns.

There have been multiple calls to eliminate active shooter drills, or at least the more realistic ones. Although the headlines can be scary at times, the world is not as scary as those simulations would have kids believe. The gun violence prevention organization Everytown for Gun Safety advises against them, noting that 0.2% of gun deaths occur in school, while drills were practiced in 95% of schools in 2015. 16. Those are the most recent figures available, but there's no reason to think drill use has declined. Drills can even be counterproductive, the organization says, because shooters tend to be current and former students learning how the school will react to a shooting and possibly how to bypass protections.

In 2023, 57 people died in school shootings, compared to drastically higher rates of off-campus suicide and homicide. If we want to save more children's lives from gun violence, we should work harder to prevent teen suicide, intercede more quickly when young people show signs of emotional distress, and regulate access to guns.

Understandably, some parents and schools want students to know how to protect themselves in dangerous situations. States should provide some solid guidelines on how to conduct drills, keeping in mind that children's mental health is just as important as their physical health. In neighborhoods where students hear gunshots and worry about their safety, experts say, the drills can be especially frightening. There is no reason why young children need to know that a drill involves an active shooter, especially given the small chances of such a thing happening. They can give their drills nicknames or, as some schools do, call the lockdown something like “dark and quiet,” which describes what to do without inducing nightmares.

School shootings are terrible to watch. But the horror should not lead us to believe that they are more common than the data tells us, or that schools can somehow get out of it.