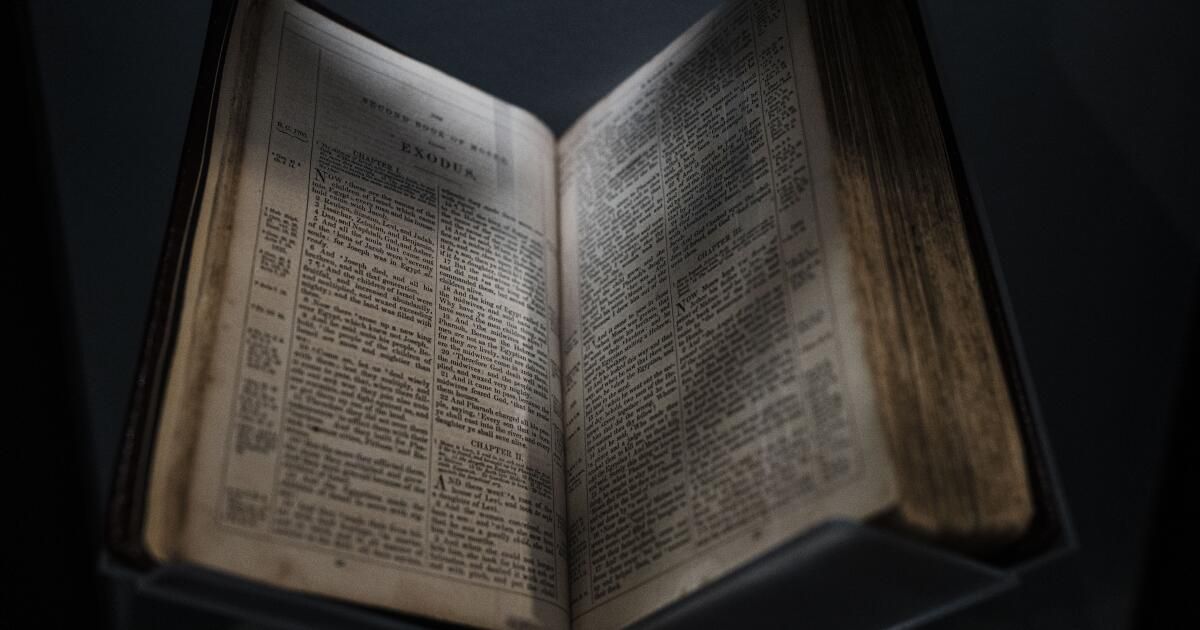

For those who supposedly revere the Founding Fathers, some Christian conservatives seem to have no problem ignoring one of their most deeply held principles: the separation of church and state. Now, Oklahoma's schools chief is requiring all public schools to teach the Bible from fifth through 12th grade, arguing that it is necessary to understanding the country's history. Rather, it is an attempt to ignore much of that history.

The Bible can have a valid place in public school classrooms. In a 1968 case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that while daily Bible reading in Pennsylvania schools was an unconstitutional attempt to inculcate religious teachings, the Bible can be part of the curriculum “when objectively presented as part of a program of secular education.”

Literature, for example, is full of biblical references. How could students understand John Steinbeck’s classic, “East of Eden,” if they were not familiar with Eden or the story of Abel and Cain? Shakespeare’s works are full of biblical references. Comparative religion classes are another appropriate place to visit the Bible in public school; the AP World History course includes a unit on world religions.

But that's not what's happening in Oklahoma, where, by the way, teachers were already free to use the Bible if it was relevant to an object or secular lesson. In a memo, state Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters said the Bible and the Ten Commandments should be taught in the classroom because of “their substantial influence on our nation's founders and the founding principles of our Constitution.”

Although he didn't say it explicitly, Walters' language clearly implies what the First Amendment was intended to prevent: America being governed as a Christian nation. It is, to be sure, the predominant faith in the country, but the Constitution forbids religion from being imposed on others by popular vote or political fiat.

In her new guidelines for teachers, Walters is at pains to repeat the line about using the Bible only in the context of literature, history, art, etc., but her guidelines require teachers to use it to conduct close literary analysis of the writings. This is certainly an unusual choice in lieu of the genius of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ernest Hemingway, Maya Angelou, and others. Because teachers have limited teaching time, the mandate leaves out great literary works and consideration of great non-Western cultures.

The careful wording cannot obscure what is clearly an effort by Christian conservatives to blur the line between church and state in the classroom, especially in a country that is growing in religious diversity. This coincides with the recent order by Louisiana’s governor to place the Ten Commandments in public schools and a recent decision by Oklahoma’s state board to approve a Catholic charter school. Charter schools are privately operated but publicly funded, and the state Supreme Court rejected the use of taxpayer money for a religious school.

More moves to introduce Judeo-Christian religion into schools are expected. It is unclear, given recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings, whether the current court majority will respect the wise precedents that preserved intact Thomas Jefferson’s “wall of separation” between church and state. The current wave of Christian nationalism should, if anything, prompt the justices to keep that wall as strong and clearly delineated as their predecessors did.