California lawmakers passed a bill eliminating money bail in 2018, but voters killed the major reform in a tumultuous 2020 after a fear-stoking referendum campaign led by the bail bond industry. Now the state is inching toward more modest improvements put in place by judicial policies and lawsuits, leaving us with a fragmented system that is too slowly and inconsistently rolling back the role of wealth and poverty in determining who gets out of prison. before the trial. .

That left leadership in the hands of other states. The Illinois General Assembly passed a law in 2021 that made the state the first in the country to eliminate money bail. Opponents (again, supported by the bail bond industry) sued, but the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the law last year. Now arrested people stay in jail, regardless of how much money they have, if a judge deems them too risky to public safety to be released. Those not considered a risk are released, sometimes with conditions such as ankle monitors, no matter how empty their wallets may be.

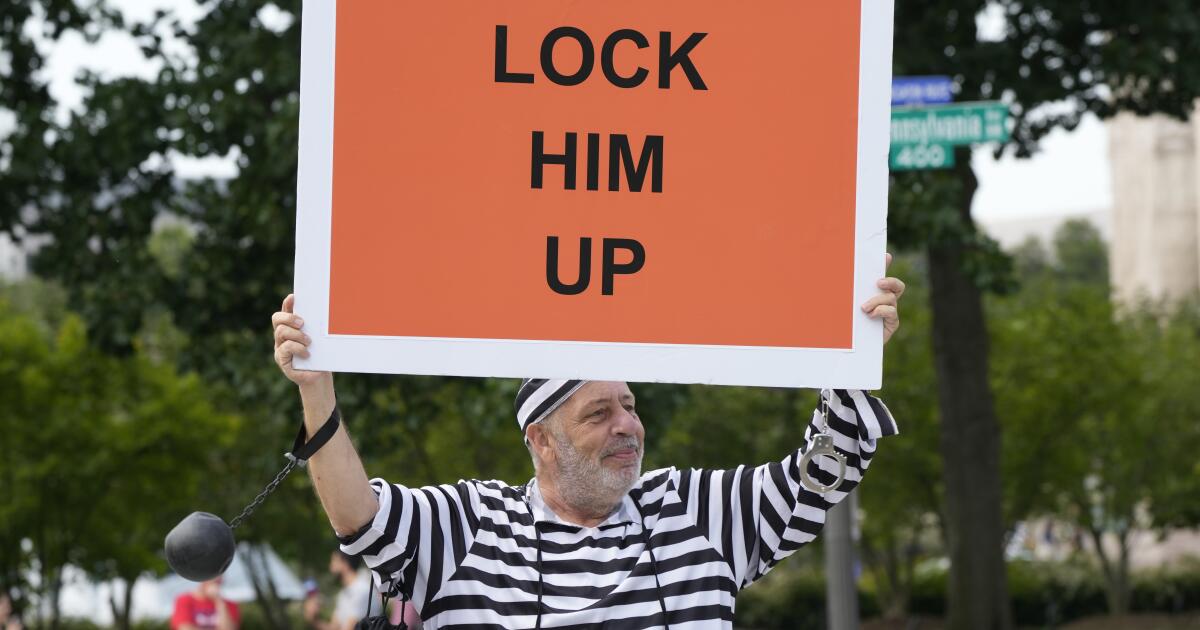

Bail reform opponents predicted chaos. Too many criminals would be caught, fined and released to commit more crimes, they said.

They were wrong. Nearly a year later, data shows that Illinois' no-bail program is working quite well. Arrests for new crimes committed by people released pending trial so far amount to about 4% in Cook County, which includes Chicago and much of the state's crimes. This is on par or slightly better than the arrest readmission rate of recent years before reform. Defendants who promise to show up for their hearings do so, for the most part. Arrest warrants are issued for the approximately 10% who do not; again, about the same proportion as the proportion previously released before trial with or without having posted bail.

The number of new arrests and failures to appear in the other 101 Illinois counties ranges from similar to much lower.

The no-bail program has some costs, for example, at trial. Judges who in the past might have decided to hold or release defendants based on their ability to pay now spend more time in pretrial hearings weighing arguments and evidence. This is how it should be. Imagine a system in which a court makes convictions or acquittals based on the amount of money the defendant pays, rather than the weight of witness testimony and other evidence.

Such a system would be the very definition of corruption and injustice. However, that is what money bail systems do during the pretrial period.

There are benefits too. Billions of dollars in bail payments that were once extracted from families, often those who could least afford them, can be used for housing, food and other daily expenses. The burdens of poverty disproportionately borne by people of color no longer automatically translate into disproportionate pretrial incarceration. The prison population in Illinois is declining, meaning less taxpayer money is being spent to feed and house people whose release would be safe.

The biggest losers in Illinois are, unsurprisingly, members of the bail bond industry, including the agents and the sureties (in effect, insurance companies) who work with them.

Illinois' no-bail system is leaps and bounds ahead of Los Angeles County's extremely modest program. For one thing, the program designed and operated by the Superior Court only applies to low-level crimes. Anyone charged with a felony is not eligible to be released without bail, but ironically, they can still be released and, in some cases, has to be released, if they pay their bail, even if they are at high risk to public safety.

The Los Angeles program, on the other hand, only applies to the brief pre-arraignment phase: the period between arrest and a defendant's initial appearance before a judge, which is typically just two or three days. A defendant who is released from the police station could be out for 30 days and then, at arraignment, be ordered detained again, or even ordered to pay monetary bail.

More than two dozen cities are suing the Superior Court in the wildly mistaken belief that using risk factors to determine which defendants to detain and which to release, rather than payments, somehow makes the public less safe. City officials may mistakenly believe that defendants out on bail will lose their money if they are arrested again while awaiting trial. Defendants lose their money only if they don't show up for hearings, and usually not even then. Bail does not provide much of a financial incentive to modify behavior.

Or they may believe that people with money are naturally riskier than people without money, even though there is no evidence to support this.

Or perhaps they are simply too eager to listen to the fairy tales told to them by members of the same industry that defeated bail reform in California four years ago, but fortunately failed to do the same in Illinois.