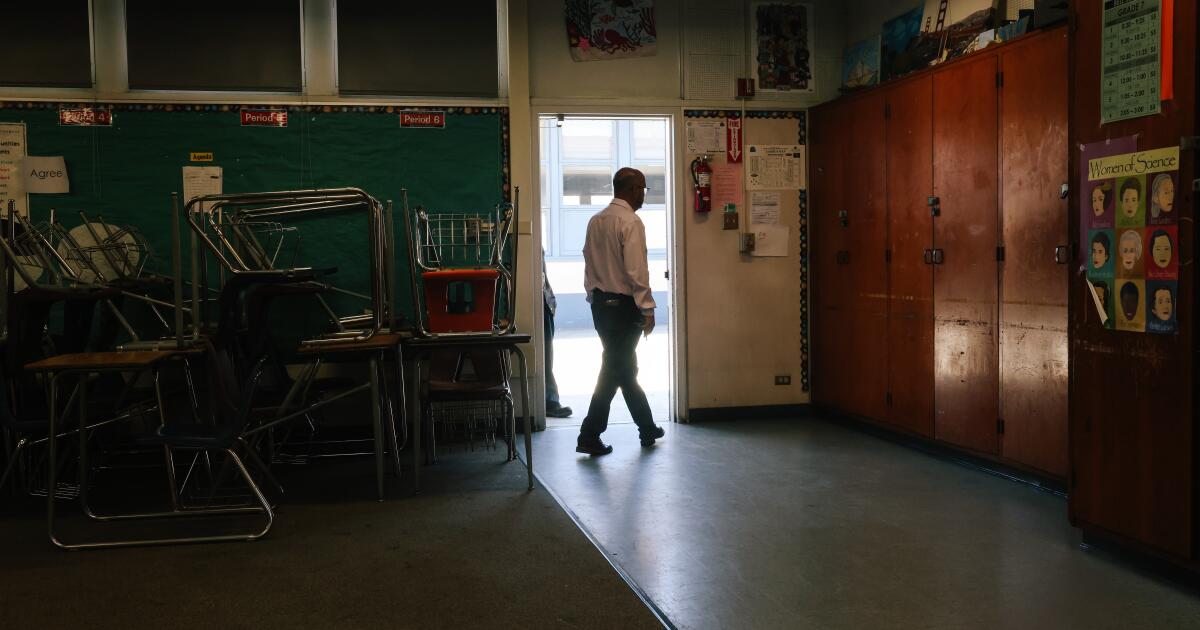

Just a month after taking office in 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom traveled to a rural school in the Central Valley and chanced upon a more prescient backdrop than he had planned: a blackboard in a classroom that posed the “Essential question: how to respond to challenges?”

The governor had chosen Riverview Elementary School in Parlier to stage his first bill signing, a stopgap solution to provide tens of millions of dollars to purchase bottled water for communities with contaminated wells. “Can't we even provide basic drinking water to over a million Californians?” Newsom said, before posing for photos where the water fountains had been sealed for more than a year. “Pathetic.”

He promised to find money to finance permanent solutions to the problem, which is most prevalent in the Central Valley. “I don't deserve to be your governor if I can't find a way to do it.”

A few months later, he and the Legislature found funding: $1.3 billion over 10 years to help hundreds of small water districts that rely on groundwater from wells that have dried up or become contaminated with agricultural and industrial waste.

Finding the money turned out to be the easy part. Five years after the governor's visit, Riverview students still drink bottled water.

Faced with attitudes toward state government that range from distrust to low expectations, Sacramento officials have struggled to forge alliances in communities divided by class and race. For once, the State has money, as well as greater authority to force changes. What is missing is leadership to disrupt a process in which intolerable delays are accepted as inevitable.

The State Water Resources Control Board, which administers the $1.3 billion drinking water program, has awarded hundreds of millions of dollars in planning, technical assistance and construction grants, and some progress has been made. But water districts are joining the list of failures as quickly as they are leaving it. Of California's more than 3,000 water districts, the most recent data shows 386 systems are failing, 507 at risk and 403 more potentially at risk.

The state's inability to overcome the crisis is partly due to complications aggravated by intransigence, partly due to better data and stricter security standards involving more systems, and partly due to drought and climate change. But it is also due to dependence on a state agency created for regulatory functions, now called to collaborate with polarized and distressed communities and guarantee the construction of pipelines. The water board was particularly offended by the title of a recent state audit that criticized its lack of urgency; It is difficult to see how any other word could be appropriate.

The red dots on the water board's map tracking water systems that rely on unsafe or dry wells are clustered in unincorporated, overwhelmingly lower-income areas, home to people of color, historically excluded from cities by compacts racial and red lines. Forced to live in places without public services, they dug wells, and when the wells ran dry, they dug deeper. The most realistic solution for many of these communities is to consolidate, with the local governments that historically excluded them.

In Tulare County, hostility is now more veiled than in the 1970s, when the General Plan deemed 15 communities unviable and recommended suspending public services, including water, so that they “enter a process of natural decline over time.” long term” and disappear. There are still thirteen left. One of them is Tooleville, 77 homes separated from the Sierra Nevada foothills by the Friant-Kern Canal, filled with water that residents cannot touch. The state pays for each home to receive six five-gallon jugs every two weeks.

For decades, the solution has been clear: connect Tooleville to the city of Exeter's water supply, less than a mile away. Exeter repeatedly refused. After state money became available to cover additional costs, and it appeared the city had run out of excuses, the council voted unanimously to break off talks. “We have our own problems” Exeter Mayor Mary Waterman-Philpot told a room full of Tooleville residents, huffing at the idea that the state would pay for the one-mile extension. “I wish Santa Claus would come and do things too.”

Finally, the State ordered them to consolidate; An agreement was reached last year. A short-term solution to connect Tooleville homes to Exeter water is supposed to be in place by September, but the full project is estimated to take eight years.

In the nearby village of Tombstone, a $3 million project that was supposed to be completed in 2022 is now a $6 million project estimated for completion in late 2026, delayed by difficulties negotiating with landowners. needed to travel one mile. pipe to connect to a nearby system.

Such events, as Newsom has said about the overall water crisis, would not be tolerated in Beverly Hills. Of the many entrenched inequalities that plague California, the undisputed goal of clean water should be relatively achievable.

The essential question on the Parlier school blackboard remains as unresolved as the solution to the school's water supply: how to address the challenges.

Newsom goes on record: “That we are living in a state with a million people who do not have access to clean, safe and affordable drinking water is a shame.” In 2019, he took his cabinet to the Central Valley to emphasize to his main collaborators the importance of the issue of drinking water. In the first State of the State, the governor highlighted that correcting the crisis “would require political will from each and every one of us.”

Newsom needs to renew and revisit that commitment, and use both his power and his pulpit to analyze delays and impose urgency, so that actions live up to the rhetoric.

Miriam Pawel is the author, among other books, of “The Crusades of César Chávez: A Biography.” She is working on a history of the University of California.