It's hard to imagine a worse decision than Thursday's Supreme Court ruling allowing Texas to use its newly designed congressional maps to elect five more Republicans to the House of Representatives. In a 6-3 decision, the six conservative justices opened the door for states to adopt unconstitutional voting laws, with immunity from judicial review for at least one election.

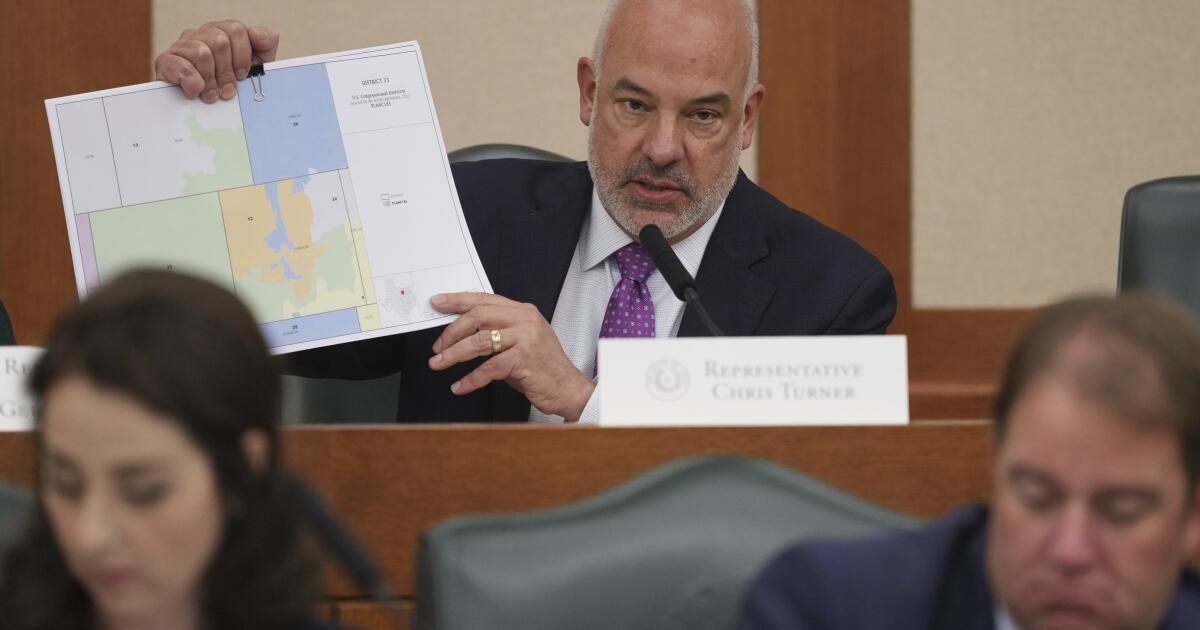

At President Trump's urging, the Republican-controlled Texas state Legislature redrawn congressional districts to help Republicans retain control of the U.S. House of Representatives. Governor Greg Abbott signed this law into law on October 25. It was immediately challenged in court.

In accordance with federal law, the case was tried by a three-judge federal court. The judges held a nine-day hearing, which included testimony from nearly two dozen witnesses and the presentation of thousands of pieces of evidence. There is a factual file of more than 3,000 pages. In a 160-page opinion, with the majority opinion written by a Trump-appointed judge, the federal court concluded that Texas impermissibly used race as a basis for drawing electoral districts. The Supreme Court has held for more than 30 years that it violates equal protection for the government to use race as a predominant factor in districting.

However, the Supreme Court overturned the district court's decision and will allow Texas to use its new districts. The court gave three reasons.

First, he said the lower court “failed to meet the presumption of legislative good faith.” But this is belied by the overwhelming evidence cited in the district court's opinion that the Texas Legislature achieved its goal of creating more Republican seats by using race to draw electoral districts. No “presumption” was appropriate: the lawmakers' motives and methods were explicitly on the record for the lower court to evaluate.

One of the most basic principles of jurisprudence is that appellate courts must accept the determination of fact made by lower courts unless it is clearly erroneous. The Supreme Court ignored this and gave no deference to the detailed facts found by the federal district court.

Second, the Supreme Court said the district court erred by failing to produce “a viable alternative map that met the State's avowedly partisan objectives.” This is a surprising argument: It claims that the only way the lower court could have declared race-based redistricting unconstitutional would be by devising a different map that would have also created five more Republican-controlled congressional districts. What if there was no way to draw such a map without using race in impermissible ways? Surely that should not be a basis for accepting unconstitutional government action. As Justice Elena Kagan said in her dissent, “the absence of the map does not make direct evidence of race-based decision making disappear.”

Finally, the court said the challenge to the new districts came too close to the next election: the November 2026 midterms. The justices' majority opinion stated: “This Court has repeatedly emphasized that lower federal courts should not normally alter election rules on the eve of an election.” This is the “Purcell principle“, from a 2006 Supreme Court order in Purcell v. Gonzalez, that federal courts cannot strike down laws relating to an election too close to the start of voting. On Thursday, the Supreme Court said the three-judge court violated this rule by improperly inserting itself “into an active primary campaign, causing much confusion and upsetting the delicate federal-state balance in elections.”

The Supreme Court has never explained the basis for the Purcell principle and did not do so here. Regardless of the timing, it makes no sense that a state government can violate the Constitution and be immune from judicial review by holding an election. But the court's decision in the Texas case expands Purcell's principle like never before. Even in a case like this, when there was no possible way to file an earlier challenge or obtain an earlier decision, the Supreme Court still says there can be no judicial remedy for unconstitutional government action.

Abbott did not sign the bill for the new districts until late October. The plaintiffs sued immediately. The district court acted as quickly as possible and issued its ruling on November 18. This did not occur on the eve of the elections, but almost a year before; midterm exams It's November 3, 2026. And yet the Supreme Court said there could be no legal challenge.

The implications of this are staggering. It means that if a state waits long enough to adopt an unconstitutional restriction on voting or redistricting, it will be completely immune from any challenge until after the next election. Kagan expressed exactly this point of disagreement: “If Purcell prevents such a ruling, it gives every state the opportunity to hold an illegal election.”

The Supreme Court's ruling in the Texas case means there can be no challenges to the new districts in California under Proposition 50, or for that matter to those that were drawn in Missouri or North Carolina. We will see next November what it means for control of the House of Representatives. But we can already see that the Supreme Court has abdicated its most important role: enforcing the Constitution.

Erwin Chemerinsky is the dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.

Perspectives

Perspectives from the LA Times offers AI-generated analysis of Voices content to provide all points of view. Insights does not appear in any news articles.

point of view

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. Content is not created or edited by the Los Angeles Times editorial staff.

Ideas expressed in the piece.

The author argues that the Supreme Court's decision represents a dangerous abdication of judicial responsibility that allows states to adopt unconstitutional election laws with effective immunity from review. The article emphasizes that the lower court conducted an exceptionally thorough fact-finding process, holding a nine-day hearing with nearly two dozen witnesses and thousands of exhibits, resulting in a 160-page opinion and a factual record of more than 3,000 pages, but the Supreme Court ignored well-established appellate principles requiring deference to the district court's factual findings. The author argues that the Court's requirement that challengers produce an alternative map that would achieve the state's partisan goals while avoiding racial gerrymandering is logically absurd, as it essentially requires courts to validate unconstitutional government action if a race-neutral alternative does not exist. Regarding the Purcell principle, the author argues that the Court's application is unprecedented and illogical, noting that since the bill was signed in late October and the district court ruled in mid-November, the challenge occurred almost a year before the November 2026 election (hardly “the eve of an election”), and yet the Court barred judicial relief. The author warns that this ruling creates a perverse incentive structure where states can time the adoption of unconstitutional voting restrictions to escape judicial review, effectively granting constitutional immunity to government violations if implemented strategically.

Different points of view on the topic.

The Supreme Court majority concluded that the lower court made serious legal errors that justified reversal.[1]. The Court determined that Texas did not receive the presumption of legislative good faith to which states are normally entitled and that the lower court should have required the challengers to present a viable alternative map that would achieve Texas' “overtly partisan goals” without such strong reliance on race, consistent with the NAACP State Conference precedent Alexander v. South Carolina Court.[1][2]. The majority also emphasized that the lower court improperly inserted itself into what the Court characterized as an “active primary campaign,” upsetting “the delicate federal-state balance in elections,” and the Court noted that the candidate filing deadline was just 17 days away when the lower court issued its ruling.[1]. Justice Samuel Alito's separate opinion acknowledged that partisan motivation drove the redistricting, but emphasized that under Alexander, it was “critical that opponents produce an alternative map,” which they did not do.[1]. Texas Republicans and state officials argued that the redistricting was purely partisan in nature and necessary, and state representatives characterized the new map as a representation of Texas “doing it right.”[3]. The Supreme Court's broader reasoning reflected concerns that the Purcell principle exists precisely to prevent judicial disruption of election proceedings once campaigns are underway, and that allowing the lower court's order to stand would create confusion and uncertainty for candidates and voters.[1].