For more than two decades, the U.S.-China trade relationship has been at the center of the globalization story: low-cost goods for American consumers, rapid growth for China, and an intricate web of supply chains linking the world's two largest economies. The hard-working, innovative and industrious Chinese people have been an essential partner in that story.

But economic relations are strategic options. What once seemed like a path to shared prosperity has become a structural imbalance that weakens America's autonomy. It is time to end our excessive trade dependence on China, not because of global tensions or hostility, but for the sake of pragmatism.

This is not an argument against global trade or ending relations with China. It is an argument for better trade. It is about strengthening—not rebuilding—America's economic strength by deepening our commitment to democratic, market-based nations while reducing exposure to a single authoritarian power that exerts disproportionate influence over our economy.

The economic facts are stark. In 2024, US exports to China amounted to approximately $143 billion, while imports from China reached nearly $439 billion. This imbalance produced a trade deficit of more than $295 billion, the largest bilateral deficit maintained by the United States. Total trade between the two countries approached $659 billion. Some economists have argued that large and persistent deficits with China have contributed to US job losses since China's accession to the World Trade Organization in December 2001.

Those numbers may not matter if trade were evenly distributed across sectors and partners. But much of this dependence is concentrated in strategically sensitive industries. Nowhere is this more dangerous than in the case of rare earth elements, which are fundamental to almost all advanced technologies, from semiconductors, electric vehicles, wind turbines and smartphones to radars and precision-guided defense systems. China also accounts for the majority of rare earth production and nearly 90% of its processing worldwide.

For years, importing these materials from China seemed cheaper than producing them at home or working with allied suppliers. But a low price does not guarantee security. A single policy decision by Beijing, for example, could send shockwaves through U.S. defense manufacturing, clean energy industries and many industrial supply chains.

In recent years, Chinese restrictions on gallium and germanium exports have shaken global electronics supply chains. When the pandemic hit in 2020, American hospitals scrambled to source protective equipment from factories thousands of miles away. This dependence is not simply an economic risk: it is a strategic vulnerability, affecting supply chains and distorting the political decisions we make. When mission-critical industries depend on inputs controlled by an authoritarian state, economic dependence can turn into political influence.

There is another consequence of our trade relationship with China that is often overlooked: the volatility of financial markets. Over the past decade, U.S. stock markets have swung repeatedly on news of tariff announcements and tensions between the superpowers. Investors know that any sign of trouble in the U.S.-China relationship can threaten corporate profits and increase market volatility. In contrast, trade with stable democratic partners is less prone to abrupt political shocks. Diversifying and balancing trade toward democratic, market-oriented nations would likely reduce the frequency and intensity of these market gyrations, offering greater predictability for companies and their investors.

The United States has always thrived in open economies governed by fair competition. The right response to our current challenge is deeper engagement with nations that share those principles: countries like Japan, Australia, England, Canada, Mexico, the Philippines, South Korea and EU member states. Many of these trading partners are already investing in new rare earth supply chains and other critical industries to reduce overdependence on China. By working together consistently over a long period of time, democratic nations can create diversified and independent markets that enhance collective security and competitiveness.

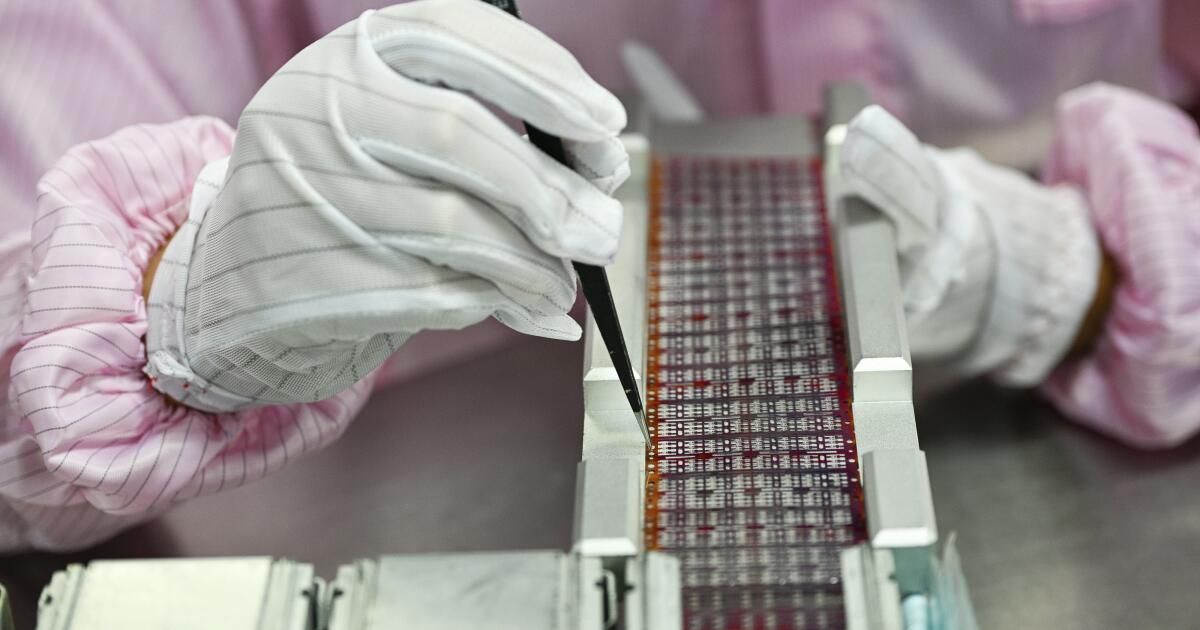

The same logic extends beyond minerals. Strategic industries—semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, automobile manufacturing, energy components, and medical supplies—must be anchored at home among trusted partners. A networked global system based on open markets and shared rules is not only more secure than dependence on a single country, but also more innovative, more inclusive, more resilient and more stable. And it would help better insulate global financial markets from geopolitical shocks linked to a fickle bilateral relationship.

Critics call efforts to reduce dependence on China “decoupling,” as if that means turning inward. That's not true. Reducing its overreliance on trade with China will reaffirm America's leadership in free and open markets and help the United States and its allies better align their economic strategies with market transparency and long-term security. Delaying these steps only increases the cost. Each year of dependence deepens the imbalance and reduces the flexibility of the United States. Rare earths may be the clearest example, but they are not the only one. Concentration in China spans many areas of manufacturing, creating risks that the United States can no longer ignore.

The Chinese people will continue to prosper and innovate, just as they should. But over time, the United States will have to chart its own course, one that is safer and based on economic principles. That means bolstering national capacity in industries where it matters most and building deeper, freer trade relationships with democratic, market-based partners that complement our core competencies.

Ending our overwhelming dependence on China for trade and commerce does not mean ending the relationship. Many of the existing ties between our two countries, which have been cultivated since President Nixon's visit to Beijing in 1972, should, of course, continue to benefit both nations.

The current trade relationship with China is no longer constructive. Achieving change will take time (more than a decade) and require great commitment. But ending that dangerous dependence and embracing new, open markets with trusted allies is a long-overdue renewal that will make a difference as we navigate the uncharted waters of the 21st century.

Christian B. Teeter teaches global business and international economics at Mount Saint Mary's University in Los Angeles.