Over the weekend, the federal government temporarily cut off funding for its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, leaving more than 42 million Americans unsure of how they will be able to feed their families in the coming weeks. For many older Californians like me, that limit is no mere inconvenience. It's a punch in the stomach.

I am now 67 years old, widowed, and living in affordable Section 8 housing in the Hillcrest area of San Diego. To qualify for my building, residents must be at least 62 years old and earn less than $58,000 a year, approximately 50% of the area median income. However, my rent still represents about 30% of my income, the standard limit for “affordable” housing. It's a dilemma that many older people know well: if we earn too much, we lose assistance; We earn very little and cannot cover basic expenses.

I work part-time as a writer, which gives me purpose and helps me stay active. But even with that income and my monthly Social Security, it's a struggle. Over the past two years, my monthly SNAP benefits of $194 have closed that gap. Without them, I'm not sure how I'll manage.

Nearly six million Californians are 65 or older according to the last census, about 15% of the state's population. Recent data shows that approximately 9% of older adults in California face food insecurity, meaning up to half a million seniors across the state struggle to reliably access three nutritious meals a day. In San Diego County alone, more than 182,000 seniors experience food insecurity, and nearly 100,000 seniors receive SNAP or CalFresh benefits. These are not extravagant stipends; The average senior household receives about $188 a month, but those modest funds often mean the difference between skipping a meal and buying a bag of groceries.

Most of my neighbors are between 70 and 80 years old. Many are immigrants from Mexico, China and Russia, each bringing rich stories and quiet resilience to our community. Most don't drive; They take the bus, use walkers or push metal carts to carry groceries. Every Thursday around noon the LGBTQ Center down the street offers a small selection of food and once a month they distribute fresh vegetables. At the same center, Jewish Family Service serves a free weekday lunch. It's about a half mile each way, and I often see neighbors walking uphill, lugging bags of oranges, apples, and onions back home. I admire your determination, but I also see how difficult it can be. There is no way most will be able to get to another food bank across town if these benefits disappear.

Food banks do heroic work, but they can't fill the void left by federal cuts. Seniors with diabetes or heart disease often need low-sodium, high-protein foods, items that are expensive and rarely available through mass food donations or food bank box programs.

And even when products are available for free, bringing them home can be a tough ordeal for someone in their 70s with arthritis or limited mobility. The federal government's decision to suspend SNAP is defended as “fiscal discipline,” but there is nothing discipline about forcing vulnerable people to choose between rent, medicine, and food. These programs are not charitable; They are investments in public health and human dignity.

Research by public health and nutrition experts, including recent studies in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity and the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics – has shown that older adults who maintain consistent nutrition have lower rates of hospital readmission and fewer chronic disease complications, saving taxpayers money in the long run. However, too often public policies focus on short-term budgets and not long-term health.

I've heard people say, “Just get a job.” Many of us already have one. Or two. But working into your 60s or 70s doesn't guarantee stability, especially when wages are low, rents are high, and retirement savings are scarce. Not everyone has savings. Life happens (illness, job loss, caregiving, divorce, unexpected medical bills, or in my case, the sudden loss of a spouse) and what once seemed secure can disappear overnight.

Others may say, “Families should take care of their elders.” Some of us are lucky to have family around. Many are not. Isolation is one of the silent epidemics among older adults and hunger only aggravates it. What worries me most is that older people have become invisible in this national conversation. Politicians talk about supporting families and especially children – both worthy causes – but they rarely talk about the older Americans who built those families, worked for decades, paid their taxes, and now live with dignity on very little.

As benefits are canceled this week, I urge federal policymakers not to forget us. For the sake of millions of people in California and the United States, we must restore SNAP immediately and protect it permanently. More than that, remember the faces behind the statistics, the woman with the walker balancing bags of oranges, the widower who skips lunch so his dog can eat, the part-time worker deciding between grocery shopping and gas.

Older people deserve to eat, live and grow old without fear of hunger. That is not a privilege; It is a promise this country once made to its people, a promise that must be kept.

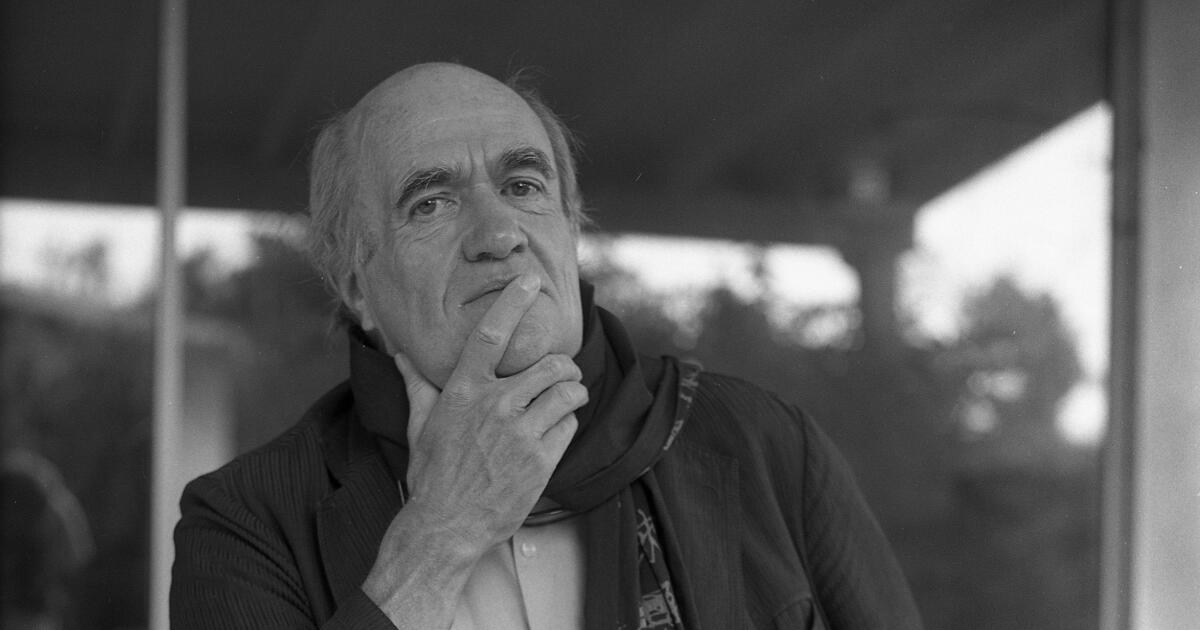

Candice Reed is a journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times and the San Diego Union-Tribune. She is also the co-author of “Thank You for Firing Me!”