As a student teacher, I witnessed extreme inequities in the way science is communicated and taught in California elementary schools.

My first teaching experience was as a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education intern in a program that Cal Poly Pomona hosted during the 2022-23 school year. This program paired STEM majors with low-income elementary schools in hopes of exposing students to more science. I started out excited about all the ways I was going to make science interesting for the second graders in my class. I was naive.

My 7-year-olds were experiencing their first year in a classroom due to the pandemic and were way behind. They needed basic writing and math skills, and also classroom etiquette. It was a constant balance between catching up and trying to implement new district mandates, like using i-Ready, an educational computer program that is pointless when your kids can’t even spell their names yet. During that fellowship, I taught only one science lesson.

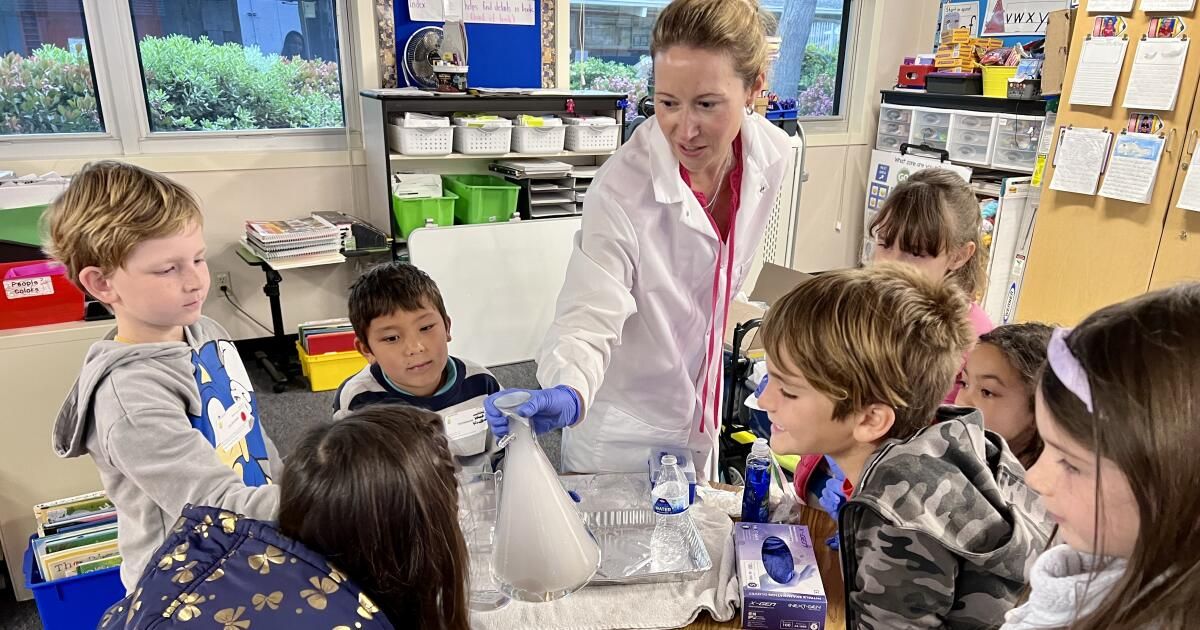

A year later, I returned to the classroom and took on the role of science educator in elementary after-school programs in low-income schools. Every week I went to different Orange County schools to teach basic science lessons, but even with rotating groups of students, I noticed a recurring theme: they were receiving little to no science education during their regular school day.

This raises a major concern: not all students receive the same quality of education they need to be prepared for 21st century jobs. A study by the California Public Policy Institute found that science education became a lower priority during the COVID-19 pandemic, although it had been a problem long before due to lack of investment.

California has guidelines for science instruction and expectations for what all K-12 students should have learned by the end of each school year. But the state does not monitor schools to ensure they meet the guidelines or conduct proficiency tests.

I have spoken to several elementary school teachers in the past about their experiences and I am happy to report that the lack of science education is not a common occurrence in all California schools. The quality of education in subjects other than language arts and math really depends on the school districts and the efforts of school boards and principals. This is not fair. All elementary students should be exposed to the science curriculum regardless of the school they attend.

It's not a California problem. Educators have been working to address this issue across the country. Jill Grace, director of the K-12 Alliance, said the U.S. has historically prioritized language arts and math, and without laws specifically mandating science or other subjects, it's easy for elementary and secondary schools to skip this curriculum.

“In California, we have a system that includes an accountability panel, and up until now the only content areas facing accountability have been language arts and math,” Grace said. “In addition, our department of education does not have content departments, while some states do.”

Fortunately, starting next year, the state's education dashboard will include science assessments, which could put a spotlight on science education in California schools. And in the last school year, $85 million It was intended to help schools teach maths and science. Although funding has been seen as the root of this problem, teachers also need training to feel confident in teaching science.

Maria C. Simani, director of the California Science Project, has also been following the issue closely and hopes that the California Department of Education will prioritize teacher training in science. Simani estimates that teachers would need at least three years of training and support to begin teaching science adequately.

Science education is not difficult to implement, especially when the target group is young children. In my experience, children are excited to learn when the lesson is practical and they can make mistakes and learn from them.

I was luckier than many public school students. I had amazing teachers throughout the West Covina Unified School District who were able to provide a well-rounded education that included life sciences and chemistry. I remember at my elementary school there were science festivals where different grades would put together a project and share it with the school; that's where I discovered my love for science. I just hope that one day elementary schools will be a place where other students find that same passion.